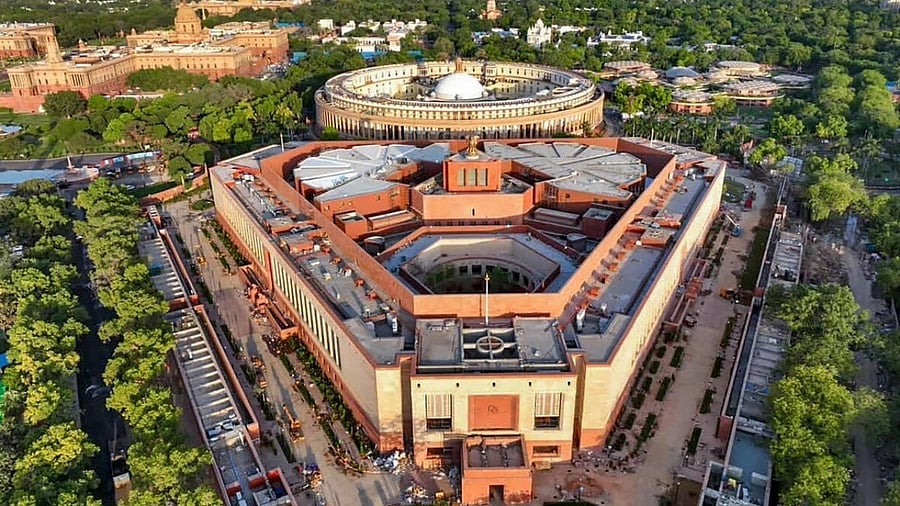

The Indian Parliament building.

Credit: PTI File Photo

The Constitution (130th Amendment) Bill and associated bills that were tabled in Parliament on Wednesday violate the principles that underlie the Constitution and the democratic polity. These bills are ill-conceived and are liable to be unfairly implemented.

They seek to punish a person before the crime is proved, as they provide for the removal of the Prime Minister, Chief Ministers, and ministers from office if they are arrested or detained in custody for 30 consecutive days for offences that attract a jail term of at least five years. The bills have been sent to a joint committee of parliament which is to return them before the next session so that they can be enacted at the earliest.

Probity in public office is important but it cannot be pursued by circumventing due process. The bills, if enacted, will become another weapon in the hands of the Central government to target Opposition parties and their ministers. Central investigative agencies, including the CBI and the ED, are now being used to hound politicians in the Opposition camp.

At present, the law and its existing processes provide them cover but the proposed laws can remove all defences, exposing anyone to politically motivated, vindictive detention. These will be the new Article 356, without its safeguards and procedures, enabling the Central government to destabilise state governments. The bills are out of tune with the essential norms of parliamentary democracy and deal a blow to constitutional federalism.

They challenge the separation of powers between the organs of state and give executive agencies unfettered power to dismiss elected governments.

The government has sought to justify the bills on the ground of public interest and the need for elected representatives to be honest and above suspicion.

But going by the Narendra Modi government’s record, these ethical and moral arguments would be mere excuses for targeted actions against the opponents. Long-drawn legal processes and low rates of conviction may have prompted the government to explore quicker ways to get at its political opponents. The bills are not aimed at cleansing the political system but at weakening the Opposition.

They are unlikely to pass the judicial muster, even if they get parliamentary approval, because they go against the basic tenet of the rule of law that no one can be held guilty till proven otherwise. The resignation of people holding office is a political matter between them, their parties, and the people. The law should have no role to play until they are proven guilty.