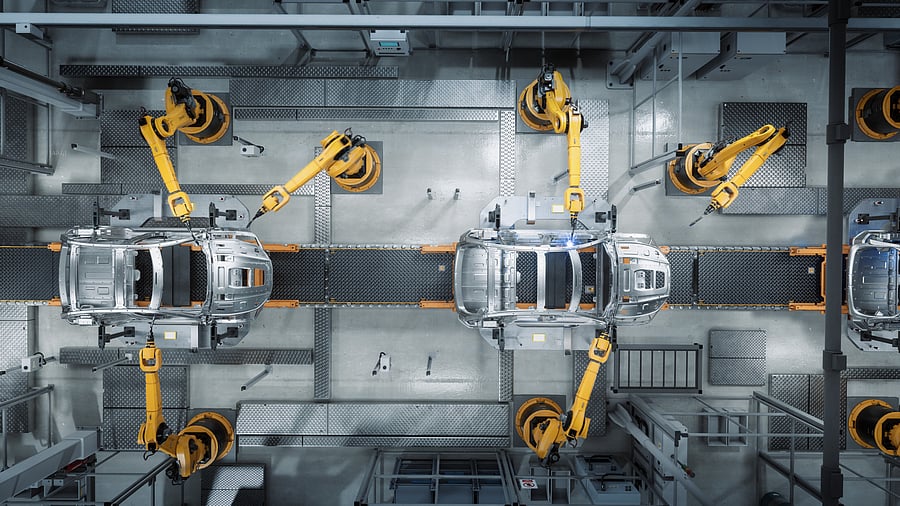

Representative image for manufacturing.

Credit: iStock

India’s GDP story is impressive. Growth has consistently outpaced global averages, reserves are strong, and India now ranks as the world’s fifth-largest economy.

Yet even the recent Economic Survey urged a pause and reflection, re-emphasising that prosperity cannot rest on headline GDP numbers alone.

Macroeconomic stability is not enough, and service exports, however valuable, cannot substitute for a strong manufacturing base. The Survey identified the central challenge as structural — building competitiveness at scale.

In a world where trade is weaponised and supply chains are instruments of state power, India must evolve from import substitution to strategic indispensability in global value chains.

The Union Budget 2026–27 presents a comprehensive “manufacturing‑first” strategy by integrating industrial growth with specialised urban hubs, doubling the electronics outlay to Rs 40,000 crore and launching India Semiconductor Mission 2.0.

To support this ecosystem, the government announced the development of City Economic Regions, rejuvenation of 200 legacy industrial clusters, and the creation of five university townships to align academic zones with industrial corridors.

Complementing these are three new chemical parks, a dedicated container manufacturing scheme, and five regional medical tourism hubs integrated with AYUSH centres, all underpinned by a Rs 10,000 crore SME Growth Fund.

Strategic corridors for rare earths, a new biopharma initiative, mandated liquidity support for MSMEs, and customs duty reliefs for critical inputs were also announced. In total, the Budget represents a push of Rs 12.2 lakh crore for manufacturing and infrastructure.

The question, however, is whether this Budget finally addresses the actual problem or risks becoming another opportunity lost. India’s history shows why this distinction matters.

For 70 years, successive governments have rolled out schemes — SEZs, tax cuts, incentives. Yet the results have been incremental rather than transformative. Kandla SEZ is 20 years older than Shenzhen, but while Shenzhen became a global symbol of industrial dynamism, Kandla remains what it was.

The pattern is clear: India’s reliance on centralised, ministry-led governance creates weak ecosystems.

Unless we recognise this gap and begin to devolve authority to empowered local governance that can build ecosystems, attract investment, and respond with agility, India will continue to underperform despite its ambitions. The world is re‑wiring supply chains; India must re‑wire its governance.

(The author is a former Chairman and Managing Director of EXIM Bank of India )

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.

TCA Ranganathan