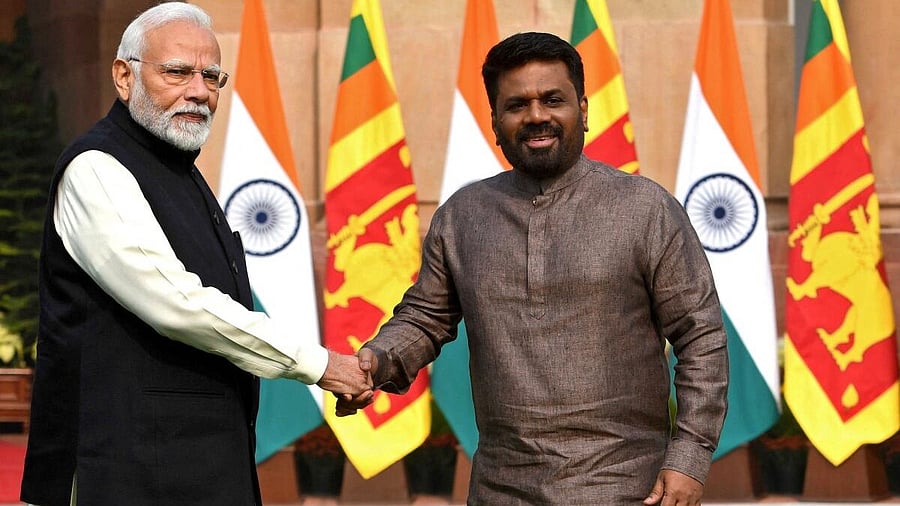

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Sri Lanka's President Anura Kumara Dissanayake

Credit: Reuters Photo

On December 16, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, standing alongside Sri Lanka's President Anura Kumara Dissanayake in New Delhi, said both leaders “are in full agreement that our security interests are interconnected. We have decided to quickly finalise a Security Cooperation Agreement”. The joint statement was less certain, stating only that both sides had decided to “explore the possibility of concluding a framework Agreement on Defence Cooperation."

A defence co-operation agreement between India and Sri Lanka has been in the air for over two decades, but has remained elusive all these years. The closest the two countries came to one was in 2003.

In a conversation with this writer, Austin Fernando, the former high commissioner of Sri Lanka to India, recalled that in 2003, when Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe visited New Delhi (Chandrika Kumaratunga was president), he had almost finalised a defence pact with Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Fernando, then defence secretary, received a call from a senior member of Wickremesinghe's entourage, instructing him to speak to the Indian defence secretary immediately. “They were in a mighty hurry,” Fernando recalled.

Until then, the 1987 Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, a pact under which the Indian Army was deployed in northern and eastern Sri Lanka, came closest to a security pact. The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), which Dissanayake now heads, carried out an armed insurrection against the Sri Lankan government for inviting Indian soldiers to Sri Lanka. However, for Wickremesinghe, in search of an international safety net during a tricky ceasefire with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a defence pact with India would have been a coup of sorts, especially after New Delhi's hands off policy since the 1990 withdrawal of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF).

Fernando could not get through to the Indian defence secretary. Within minutes though, Fernando received another call from Wickremesinghe's team. There had been a rethink. In the uneasy government of co-habitation in Colombo at the time, Kumaratunga had surrendered the defence portfolio to Wickremesinghe, but she was the Chair at Cabinet meetings, and still supreme commander of the armed forces. She was critical of the ceasefire and the Wickremesinghe government's handling of the defence portfolio. It was more than likely Kumaratunga would have lashed out at Wickremesinghe and India for reaching a defence agreement without her involvement.

Indeed, within days of Wickremesinghe’s visit, on November 4, 2003 Kumaratunga sacked the defence minister and two other members of his Cabinet. Kumaratunga later conveyed that she was ready to conclude a defence pact with New Delhi, but was informed by the Vajpayee team that it would have to wait until after the Indian elections.

When the truce between Colombo and the LTTE broke down in 2008, India helped the Sri Lankan military from behind the scenes with intelligence about on the LTTE's arms consignments coming in by sea but provided no lethal equipment. After the LTTE’s defeat in 2009, Sri Lanka’s President Mahinda Rajapaksa looked towards China, which asked no questions about Tamil civilian casualties and other human rights abuses in the final stages of the war, and was ready to fund all of Rajapaksa's vanity projects, including the construction of a port at Hambantota. In 2014, a Chinese submarine called at Colombo port, and the rest is history.

Since then, ‘both sides reaffirmed their commitment to deepening bilateral defence and security co-operation’ has been a standard line in readouts at high level India-Sri Lanka visits; but talk of anything more formal would raise hackles in Sri Lanka.

In April 2022, a memorandum of understanding for Bharat Electronics Limited to set up a Marine Rescue Co-ordination Centre for the Sri Lankan Navy, created a furore in Sri Lanka.

The Trincomalee Oil Tank Farm agreement of 2022 too raised suspicions that India would use the Trincomalee harbour as a military base. The latest joint statement says, “both leaders decided to support the development of Trincomalee as a regional energy and industrial hub”. It is, however, inevitable that an India-driven energy hub on Sri Lanka's eastern coast will offset the Chinese presence at Hambantota, and will be key to the security of the Bay of Bengal region.

Dissanayake has been praised in Sri Lanka for his India visit, his first foray into choppy geopolitical waters, and for securing India’s continued financial and other assistance. Bonus point: no mention of the 13th Amendment in the joint statement. Wickremesinghe commended Dissanayake for agreeing to continue discussions on ECTA, a bilateral trade initiative that the former president failed to push through due to domestic opposition. Fernando said the visit was “very productive” and “constructive”, and the joint statement “positive” and “crafted in a way so as to not cause concern in the minds of some of our partners”.

What's also different this time is that those who were among the first to rise up in protest against alleged Indian designs on Sri Lanka are now running the government with a sweeping mandate from across the country, and they enjoy the luxury of having virtually no opposition.

The irony of a JVP leader agreeing to discuss a defence pact with India is not lost on anyone. But if there is ever a chance of Sri Lanka and India signing a defence pact, this is it.

(Nirupama Subramanian is an independent journalist. X: @tallstories.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.