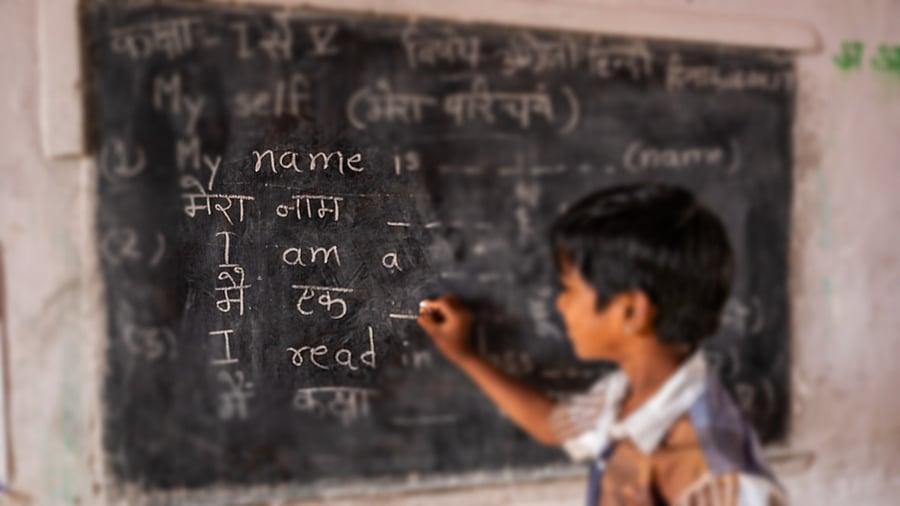

A schoolboy is seen learning to write in Hindi in this representative image

Credit: iStock Photo

'Nanage Hindi gottilla.’ (I don’t know Hindi, as a Kannadiga would articulate.)

Why should acknowledging one’s linguistic identity be seen as defiance? If India truly celebrates its multilingual fabric, why does asserting the right to one’s own language invite objection?

Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M K Stalin’s recent remarks against the Centre’s alleged Hindi imposition resonate deeply in a state that has long viewed language as inseparable from its cultural and political autonomy. The opposition is not against Hindi as a language but also against its perceived systematic prioritisation in governance, policymaking, and administration — despite India’s constitutional commitment to linguistic plurality.

The renaming of legal codes, the predominance of Hindi in government schemes, and the subtle relegation of regional languages to secondary status fuel fears of an orchestrated attempt to position Hindi as the primary language of the Indian Union.

A pattern of linguistic dominance

Such concerns are neither unwarranted nor unprecedented. Language has long been a potent fault line in India, capable of igniting social unrest and political upheaval.

The anti-Hindi agitations of the 1960s in Tamil Nadu were a definitive rejection of centralised linguistic hegemony. In Assam, the Bengali-Assamese linguistic conflict in the 1960s and 1970s led to violent clashes and policy reversals. The 1980s saw Punjab grappling with linguistic and religious assertions that culminated in unprecedented strife. Even the formation of states such as Telangana, Uttarakhand, and Jharkhand were deeply interwoven with linguistic and cultural identity politics.

Beyond India, linguistic tensions have been a catalyst for geopolitical fractures. The brutal Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 stemmed from Pakistan’s insistence on imposing Urdu over the Bengali-speaking population of East Pakistan. In Canada, Quebec’s French-speaking identity has persistently fuelled debates on secession. Sri Lanka’s Sinhala-only policy of 1956 marginalised Tamil speakers, leading to a devastating civil war that lasted nearly three decades. In Ukraine, the marginalisation of Russian speakers has played a role in the country’s ongoing conflict. From Belgium’s Flemish-Walloon divide to Catalonia’s linguistic assertion in Spain, language has proven to be far more than a means of communication — it is a tool of power, an emblem of identity, and, if mishandled, a trigger for conflict.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 emphasises the importance of teaching children their local state language, yet its implementation remains a challenge across India — even in states governed by the ‘double engine sarkar’. Tamil Nadu’s DMK-led government continues to resist the Centre’s push for a three-language policy, keeping the debate over linguistic imposition alive.

Meanwhile, a stark contradiction plays out — politicians champion or oppose Hindi as the pillar of national identity, yet their own children attend elite English-medium schools that offer Hindi alongside global languages like French, Spanish, or German. If their families enjoy the freedom to choose from a multilingual curriculum, why should ordinary citizens be denied the same linguistic choices?

Institutional bias

While political leaders battle over language policies, institutional bias often entrench Hindi’s dominance further. Even today, most large government and regulatory institutions have a Raj Bhasha department dedicated to the usage and promotion of Hindi. Will the Union government take steps to ensure that similar institutional structures and services are extended to all the 21 other official languages recognised under the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution?

The argument that Hindi is necessary for national unity is an oversimplification that dismisses the lived realities of millions who do not speak it. India’s linguistic diversity is not just about the number of languages spoken but also about the unique structures, sounds, and scripts that make each language distinct.

Take Tamil, one of the world’s oldest living languages, which has a phonetic system that cannot be accurately represented in English or even in Indian languages. A striking example is the Tamil letter ழ (pronounced as ḻa), a retroflex sound that has no direct equivalent in English or Hindi. This is why the word 'Tamil’ itself is an incorrect pronunciation — the true pronunciation is closer to Tamizh (தமிழ்). Yet, even Tamizh fails to capture the exact phonetics due to the limitations of the Roman script. Such intricacies highlight why India’s linguistic heritage must be preserved on its own terms, without being forced into moulds that fail to do justice to their depth and complexity.

The silent erosion of mother tongues

The irony, however, is that while political battles are being waged over Hindi imposition, urban India is already witnessing a silent erosion of mother tongues. In metropolises, younger generations increasingly default to English or the dominant regional language of their locality, often at the cost of their own native tongues. Many parents, themselves detached from their linguistic heritage, are unable to pass down their language’s script, resulting in generational linguistic attrition. This raises a fundamental question: if the real crisis is the decline of mother tongues, then is the political resistance to Hindi imposition addressing the right concern?

If English has been embraced as an economic necessity, there is little rationale for outright rejection of Hindi — provided it is not imposed but chosen. The real issue is not whether Hindi should be learnt, but whether its learning is being made compulsory at the cost of regional languages. A multilingual India should be a nation where Tamil, Bengali, Kannada, Marathi, Telugu, and all other languages flourish alongside Hindi — not beneath it.

The debate over language in India has always been positioned as a conflict between tradition and modernity, regionalism and nationalism, or imposition and resistance. In reality, the real question is about power, equality, and agency.

For politicians, language is a tool of power, as well. Linguistic affinity is a convenient way to stoke local sentiment, rally political support, and set the stage for electoral battles. In India, language serves as both a unifier and a wedge.

(Srinath Sridharan is a corporate adviser and independent director on corporate boards. X: @ssmumbai.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.