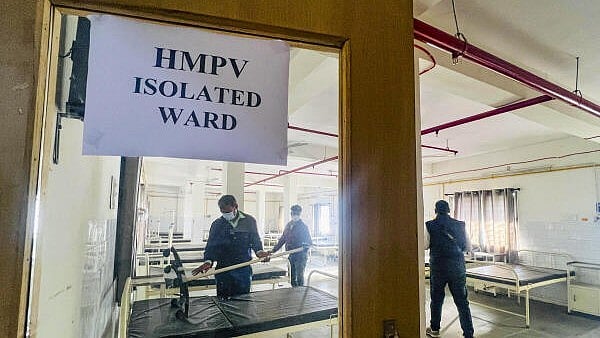

A ward being prepared for patients infected with Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV). (Image for representation)

Credit: PTI Photo

The Covid-19 pandemic, coupled with the World Health Organisation’s warnings about possible viral outbreaks, has understandably left the general population uneasy about what lies ahead. From time to time, reports of the monkeypox virus, Zika, Nipah, MERS, and SARS surface and linger in the public consciousness for weeks. Most recently, the HMPV virus grabbed local headlines, though it has been known for decades as a cause of common cold symptoms, particularly in winter.

The sudden attention on HMPV brought back pandemic fears, consuming social media, until health authorities provided reassurances and information. This may be the right time to revisit the lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic and address unresolved bioethical concerns.

The WHO noted the outbreak of HMPV in China but has not classified it as a virus outbreak of global concern. It lists HMPV among viruses that can cause influenza-like illness (ILI) and severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) in winter.

Renowned virologists, such as Dr Gagandeep Kang, have downplayed apprehensions, emphasising India’s robust surveillance systems and reassuring that current data does not warrant panic. Many viruses affect human beings, and most are effectively handled by the immune system with minimal harm.

The first thing to question is the media’s tendency to create headlines out of every reported outbreak of influenza. Such reporting fosters fear, paranoia, and unnecessary testing, often overwhelming healthcare systems. Media professionals must exercise restraint and work with health authorities to provide a balanced picture that is informative and helpful. Sensationalism can provoke negative reactions against healthcare personnel, hospitals, and patients.

The recent news report about HMPV, for instance, identified the hospital where testing occurred and described the infected paediatric patients. This breaches confidentiality and risks perpetuating stigma, as seen during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is essential to exercise discretion in reporting patient and hospital details, given the rapid spread of unverified information on social media. Health authorities must take proactive measures to counter misinformation and provide authoritative, clear guidance about official assessments, online websites, and protocols of care.

Social cohesion plays a crucial role in times of crisis. Communities, irrespective of divisive narratives, must show solidarity and provide care. Building bridges during normalcy strengthens resilience during emergencies. At the core of any crisis is a human being in distress, which should awaken compassion in all of us.

Equally important is the readiness of the healthcare system. Pandemic protocols that were recommended at the end of the Covid-19 pandemic must be implemented to strengthen public healthcare infrastructure to treat the huge number of patients that cannot access private hospitals. Cadres of health workers need to be made pandemic-ready for triage, treatment, and reassurance of patients as required, without placing a strain on hospitals. Advances in PCR testing now enable virus screening for sick patients and targeted care.

These testing kits must be made widely available but used with discretion to avoid wastage or shortage. The memory of migrants making their way home in desolation still haunts the collective memory, and the next time around, nobody should be excluded from care or sustenance, with a clear and viable public health plan accessible to all. In low-resource environments, logistics, education, and financial help remain the greatest challenges.

The capacity to manufacture vaccines was another critical factor that helped us emerge from Covid-19, and investment in this sector would be both prudent and life-saving. A plan is needed to prevent vaccine misinformation and allow patients to comply with public health efforts.

Regular budget allocations at state levels in the intervening years can boost healthcare capacity required in emergencies. Another step would be to ensure that every citizen is covered by health schemes or health outreach programmes, bridging the inequality and healthcare gap that became so painfully obvious during Covid-19. Such efforts could build citizen trust in health systems that they will be inclusive and deliver on the care required in a crisis.

In this time of reprieve, as we face an uncertain future, it may be prudent to reflect on the bioethical concerns of inequality, harms, and confidentiality, revisiting our recent experiences of Covid-19 and evaluating our preparedness once more.

(The writer is a doctor and author of Biomedical Ethics)