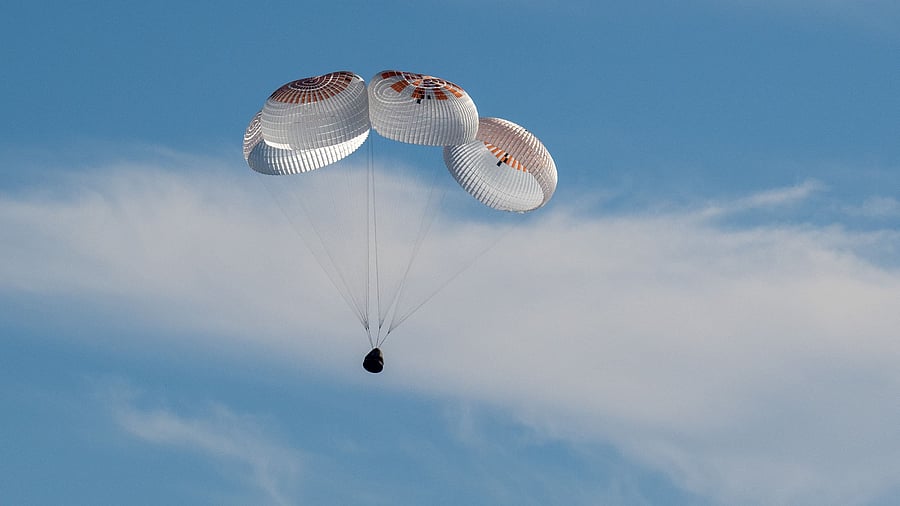

A SpaceX Dragon spacecraft is seen as it lands with NASA astronauts Nick Hague, Suni Williams, Butch Wilmore, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov aboard in the water

Credit: Reuters File Photo

What was meant to be an eight-day visit turned into an unplanned nine-month stay in space for Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore. Their presence in and departure from the ISS make a compelling trope for reorientation and adaptation in a world that is constantly evolving and is rife with uncertainties. The fundamental process of unlearning, learning, and relearning is paramount to human progress, not just in space travel, but in the domain of education, which nurtures the world’s most valuable assets – students, who are still reeling under the effects of the pandemic-induced learning deficits.

In 2018, The Guardian reported the worrisome trend among students exposed to screens, indicating their inability to cope with prolonged pen usage, weakening their fine motor skills. Recent data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in the United States in 2025 highlight the significant disparity in literacy and numeracy skills between high and emerging learners. According to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), 2023, 42% of pupils aged 12 to 18 in rural India cannot read simple sentences. Addressing these gaps is imperative since they directly affect the future of our students and society.

As various stakeholders in academia negotiate the difficulties of diminishing literacy, the Williams-Wilmore ISS odyssey offers insightful lessons on the importance of reorientation and adaptation in education. Rising techno-schools have given digital instruction top priority, often at the expense of fine motor skills. Studies on the ISS reveal that the astronauts developed problems with muscular coordination following extended microgravity exposure, which calls for rehabilitation upon returning. Similarly, intentional handwriting practice is still absolutely essential for hand dexterity even as schooling moves toward digital tools. Gradually abandoning this skill in the pursuit of modernity may hinder students’ ability to adapt in an ever-evolving world.

Prominent publications like The Guardian and Adelaide Now indicate that educational experts in Australia are expressing concern over schools prioritising the breadth of content rather than its depth. A noticeable trend here is the reduction of academic standards, ostensibly to accommodate diverse learners. An entire generation of students has experienced the pandemic, making it essential to reacquire and restore skills that were either lost or acquired late owing to this interruption. Likewise, although Williams and Wilmore clocked 565 hours in space, a battalion of researchers and medical professionals is deeply engaged in their rehabilitation to readjust to Earth’s environment. We must consider if we are prepared to invest in our most valuable future assets—our students—to assist them in recovering and enhancing the skills they have lost or acquired late. However, the latest budget has not yet allocated any funding for the same.

In 2020, a persistent trend in the high-stakes board examinations was the introduction of Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs), especially in subjects like language and literature, to alleviate students’ stress. How can educators solve this dead horse theory of which skill to inculcate in academia? Although writing and typing are categorised as fine motor skills, research from PubMed on memory, cognition, and literacy demonstrates that handwriting elicits superior brain activation, leading to improved memory retention, accelerated learning, and greater comprehension. A 2020 study from IIT Mumbai showed that students who engaged in handwriting achieved more outstanding performance in language assessments by 15% compared to those who utilised tablets for assignments.

There is a dire need for pupils to be adaptable and prepared for the future. The space exploration experiences of Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore demonstrate that flexibility and reorientation are

crucial for survival and progress. Although proficient in their domain, the astronaut duo functioned as mere learners;

they underwent continuous training to operate in both extraterrestrial and terrestrial environments.

Similarly, educational institutions must equip students to excel in digital and analogue learning modalities (without favouring one over the other) rather than disregarding fine motor abilities or simplifying the system to accommodate emerging learners. Furthermore, it is essential to recognise that literacy is no longer singular but plural. The United Kingdom is a leader in integrating multimodal literacies into its curriculum. This new definition suggests that meaning-making occurs through multiple modalities.

The United States has mandated cursive writing instruction in schools to mitigate over-digitisation problems, whereas Sweden is doing away with digital tools and reintroducing traditional learning. Achieving a balance between digital and traditional education is a nuanced endeavour, as both skills are indispensable in contemporary society. A robust education system is one that constantly offers space and resources to bounce back from the effects of unforeseen eventualities. However, our nation has yet to deliberate in the essential discussions and debates about how much digitisation is too much. Equipping students to navigate different conditions is vital; neglecting this responsibility is a disservice to our future citizens, rendering them unprepared for the challenges of a swiftly transitioning world.

(The writer is an assistant professor at St Joseph’s College of Commerce, Bengaluru, and a doctoral candidate at Christ University)