The ongoing tariff war waged on the world by Donald Trump can be traced to one simple fact, viz., the US is heavily in debt. A ballooning national debt – now over $36 trillion, growing at 15-20% of GDP. On top of this, student loan debt exceeds $1.7 trillion, and other consumer debts add another $300 billion. Japan and China together hold over $2 trillion of US debt, making America’s position increasingly precarious. To maintain its hegemonic status, the US has stationed troops in over 100 countries and fueled its six major defence contractors with roughly $350 billion annually. Washington has also manipulated the international monetary system over many decades to ensure that the dollar is the preferred currency for global trade.

The US dollar, however, is a fiat currency, backed by neither gold nor any other tangible asset ever since President Nixon ended dollar convertibility to gold in 1971. Like its citizenry, America has been living on borrowed money; it has become a credit risk, its entire economic structure resting on faith rather than real value.

The centrepiece of the international monetary system was based on the price of gold. Gold has been used as money for several reasons. It is fungible, easily transportable, malleable, and possesses unique physical and chemical properties that make it difficult to counterfeit. A gold standard is an exchange rate system in which each country’s currency is valued as worth a fixed amount of gold. After World War II, the leading Western powers adopted a new system that made the US dollar the world’s reserve currency. All currencies now fluctuate in relation to the dollar.

Some economists and others, including President Donald Trump and his former Federal Reserve Board of Governors nominee, Judy Shelton, favour a return to the gold standard because it would impose new rules and “discipline” on a central bank they view as too powerful and whose actions they consider flawed.

The current trade imbalance between the US and China may be traced to the pivotal moment when, in 1971, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger opened trade with China, drawing Western corporations eastward with promises of cheap labour, no strikes, and political “stability.” By outsourcing production, they slashed labour costs, boosted margins, and delivered higher returns to shareholders. At the same time, US consumers gained access to cheaper goods. Over a span of forty years, China has become the world’s factory. In the US, costs have soared. US manufacturing wages today average $50-$80 per hour, while professional services command $150-$300. By contrast, in countries like India, Vietnam, or China, comparable costs are one-fifth, or less.

The IMF and the World Bank, long dominated by US and European interests, have played dual roles: rescuing economies in crisis while also binding poorer nations into cycles of debt and dependency. Their influence is now being challenged as new financial institutions like the BRICS Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank offer alternatives.

Untold gold is unmatched leverage

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, one ounce of gold cost $20.67. Today, a troy ounce of gold has already gone over the $4,000 mark. If a country’s wealth is measured in terms of how much gold the country has, India would be the richest. While America still holds the largest official reserves – about 8,133 tons, and Germany is next with 3,350 tons, India, officially, has only 800 tons. Yet here is an extraordinary fact: Indian households and temples together are estimated to hold over 25,000 tons of gold – far more than any government. At $4,000 per ounce, this translates to 2,000 x 16 x 25,000 x 4,000 = $3.2 trillion. This is not merely wealth; it is potential leverage in a shifting global order.

To tap into this untold wealth, the Indian government should consider requiring its citizens and the temples to turn in 30% of their gold holdings in exchange for gold bonds, which would pay an attractive rate of interest, such as 10%. The almost one trillion dollars that is raised can be used for a variety of infrastructure projects across India to provide its citizenry with better roads, universal healthcare, clean water, clean air and sewage facilities, and manufacturing hubs so that the slogan ‘Make in India for India and the world’ can become a reality. During the Great Depression, when Americans were hoarding gold, they were ordered by President Roosevelt to convert their gold into dollars so that the US economy could recover.

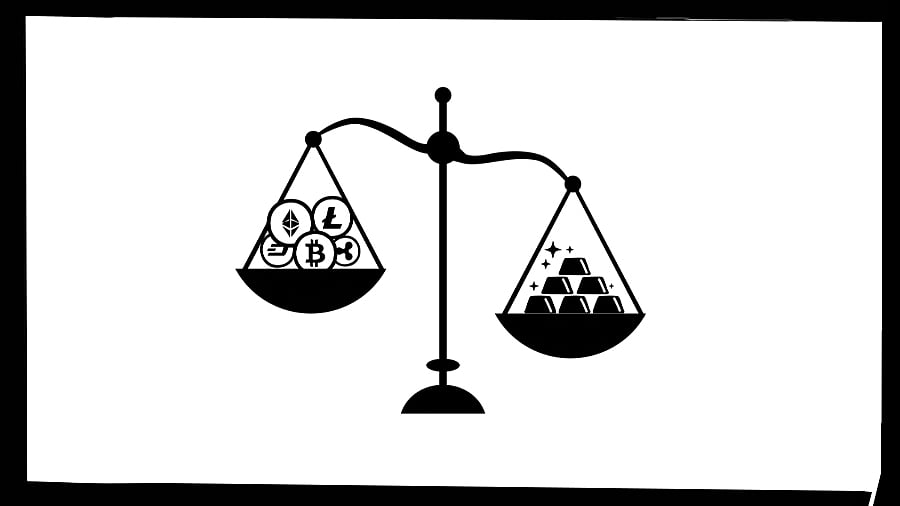

While Trump occasionally invokes the gold standard, his real goal is to promote dollar-backed cryptocurrency, the so-called stablecoin. The gold standard is invoked as rhetoric, while the real push is towards a privatised digital currency system. The cryptocurrency industry was the biggest corporate donor during Trump’s 2024 general election campaign.

This shift is revealing. Unlike fiat money, cryptocurrencies are decentralised and outside government control. Cryptocurrency relies on reliable network connectivity, but such connectivity is subject to manipulation by Silicon Valley, one of Trump’s strongest backers.

For India, the choice is stark: meekly follow a financial and monetary system dominated by US and European interests, or assert itself as a shaper of a new, fairer world order. Gold reserves – both public and private – offer India tremendous leverage. With confidence and political will, India can lead in reshaping global finance, free from the lingering colonial mindset.

The US, saddled with debt and addicted to fiat currency and speculative finance instruments, is vulnerable. Its flirtation with both the gold standard and cryptocurrency reflects uncertainty, not strength. By contrast, India’s challenge is to mobilise its dormant wealth to secure real independence and prosperity.

Is India up to the challenge? Only time will tell.

(Roger is a retired professor and writer on societal and geo-political implications of technology; Kal is an entrepreneur and consulting engineer based in the San Francisco area)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.