But through countless erratic decrees and iron-handed purges, he has carved deep scars into every facet of Libyan life. The mystery and speculation swirling about him marked a fitting close to a quixotic reign.

Gadhafi, who was a 27-year-old junior officer when his coup deposed King Idris in September 1969, viewed himself as a desert philosopher, and he declared that his political system of “permanent revolution” would replace both capitalism and socialism.

But over the years, that revolution also swept away nearly every institution that could challenge him – or guide the country when he was gone. By the time he was done, Libya had no parliament, no unified military command, no political parties, no unions, no civil society and no nongovernmental organizations. His ministries were hollow, with the notable exception of the state oil company.

“This is my country!” he roared in a televised speech when the revolt first erupted in late February, shaking his fist and pounding the dais. “Moammar is not a president to quit his post! Moammar is the leader of the revolution until the end of time!”

By Monday, the territory he controlled had shrunk to pockets of resistance in Tripoli and his strongholds of Surt and Sabha. The uprising condensed into six harrowing months an ever more destructive version of the erratic rule that Gadhafi imposed on Libya over the previous four decades.

He clung to power and refused to accept the rejection of his own people, railing against a spectrum of outside conspiracies from Islamic fundamentalists to rejuvenated colonialism. The country of 6 million people and vast oil wealth, meanwhile, gradually disintegrated. To ensure his singular role, Gadhafi had long wielded violence both at home and abroad.

He financed and armed a cornucopia of violent organizations, including the Irish Republican Army, the Red Army faction in Europe and African guerrilla groups. His government was linked to terrorist attacks, most notoriously the explosion of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988. He became an international pariah.

In the beginning, he brought the libyans relative prosperity. Libya had been desperately poor, living off the meager proceeds from exporting scrap metal left over from major World War II battles until oil was discovered in 1959. But a decade later, Libyans had touched little of their wealth.

The 1969 coup changed that. The new Libyan government forged a profound global change in the relationship between the major oil companies and the producing countries, forcing the oil giants to cede majority stakes in exchange for continued access to Libya’s oil fields. The oil producers also demanded a higher share of the profits. The pattern was emulated across the oil-producing states.

Mercurial policy changes

With the increased revenue, Gadhafi set about building roads, hospitals, schools and housing. Life expectancy, which was 51 in 1969, is now over 74. Literacy leapt to 88 per cent. Per capita annual income grew to above $12,000 in recent years, though that is markedly lower than the figure for other countries endowed with vast oil income. But Gadhafi’s mercurial changes in policy and personality kept Libyans off balance for much of his rule. To consolidate his power, he eliminated or isolated all the 11 other members of the original revolutionary command council.

In 1988, in the deadliest terrorist act linked to Libya, 259 people aboard the Pan Am flight died when the plane exploded in midair. The falling wreckage killed 11 people on the ground in Lockerbie. In an echo of that operation, Libyan agents were believed to have been behind the explosion of a French passenger jet over Niger in West Africa in 1989, killing 170 people.

In 1999, Libya finally handed over two Lockerbie suspects for trial in The Hague under Scottish law and reached a financial settlement with the French. The international sanctions against Libya were lifted in 2003 after it accepted responsibility for the Lockerbie bombing and agreed to pay $2.7 billion to the families of the Lockerbie victims and two victims of other attacks.

Tripoli truly began to emerge from the cold after the Sept 11 attacks against the United States by al-Qaida. Gadhafi condemned them and shared Libya’s own intelligence gathering on the organisation with Washington.

After the US-led invasion of Iraq, Gadhafi announced that Libya was giving up its efforts to acquire weapons of mass destruction, including a covert nascent nuclear program obtained from a clandestine Pakistani network, and said it would cooperate with the international community in destroying its stockpile.

But he always presented himself as beloved guide and chief clairvoyant rather than the ruler. Indeed, he seethed when the popular uprising inspired by similar revolutions next door in Tunisia and Egypt sought to drive him from power. He tried to crush the uprising with the same violence he had wielded to stay in power, deploying tanks and bombs against not only the rebels but also unarmed civilians.

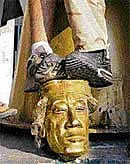

After months of inconclusive fighting, the assault on Tripoli that at last drove Gadhafi from power unfolded at a breakneck pace. Insurgents captured a military base of the vaunted Khamis Brigade, where they had expected to meet fierce resistance, then sped toward Tripoli. While pockets of Gadhafi loyalists fought pitched battles in Tripoli neighborhoods, rebels captured the Bab al-Aziziya compound that was the symbol of his power.

But Libya’s post-Gadhafi future looked to be as volatile as its past. Gadhafi said in a radio address that he had withdrawn from the Bab al-Aziziya compound as a tactical maneuver. He and his heir apparent, Seif al-Islam Gadhafi, are still at large. There was still no clear plan for political succession or for maintaining security in the country. Gadhafi’s long attempt to eliminate the government left Libya in shambles, its sagging infrastructure belying its oil wealth.