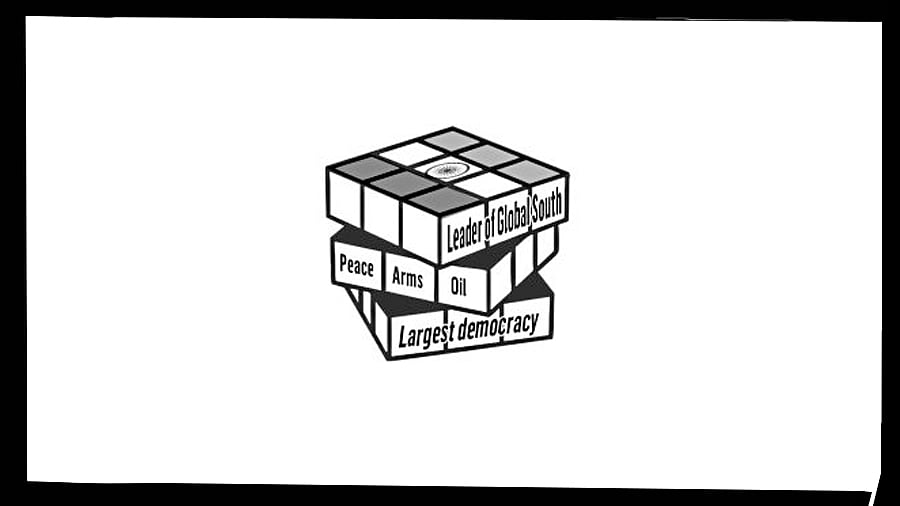

In recent years, India’s foreign policy has been cast in grand terms: as the world’s largest democracy, as the vanguard of the Global South, and as an advocate for peace and dialogue while resolutely opposing terrorism.

Yet it is increasingly difficult to discern what, if anything, India’s diplomacy actually stands for beyond grand slogans and adroit manoeuvring. The risk is that these lofty claims have been hollowed out by opportunism and realpolitik, leaving India bereft of any moral or ideological coherence, and diminishing its standing among nations.

First, consider the claim that India is the world’s largest democracy, a champion of human rights and the rule of law. That identity has deep roots.

Under Jawaharlal Nehru, in the early years of the Indian republic, India conducted free and fair elections under incredibly trying conditions, and carved out a distinct role for itself on the world stage. India’s electoral credibility and Nehru’s leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement earned it an honourable standing, despite modest economic and military resources.

However, in recent years, independent bodies such as the V-Dem Institute have categorised India as being in the “electoral autocracy” category, noting that it ranked 100 of 179 countries on the Liberal Democracy Index in 2025. Similarly, the Freedom House 2025 report gives India a “Partly Free” status, citing rising harassment of journalists, NGOs, and minority groups under the current government.

These metrics reveal a stark disconnect between India’s claim and its practice. The self-image of India as a beacon of democracy has been compromised.

Second, India presents itself as a leader of the Global South; a nation that understands the legacy of colonial and imperial extraction and stands in solidarity with other post-colonial states. Again, historically under Nehru, India developed that identity credibly: engaging with newly independent nations, forging alliances with like-minded states, and projecting an independent foreign policy not beholden to the blocs of the Cold War era.

But now the claim rings hollow. India’s recent positions on the struggles of formerly colonised and marginalised peoples — such as the Palestinian fight against Israeli occupation, the Iranian challenge to Western hegemony, or the Tibetan demand for cultural and political autonomy — reflect a pattern of selective solidarity.

When moral clarity requires little cost, India speaks. But when principle demands standing up to powerful states, it retreats into silence dressed up as “strategic autonomy”. This is not the behaviour of a principled leader of the Global South, but that of a state guided by expedience rather than solidarity.

Third, India asserts that it advocates peace, dialogue and adherence to international law, and that it stands firmly against terrorism in all its forms. Indeed, the restrained response by the Manmohan Singh government to the 26/11 Mumbai attacks helped distance India from being characterised simply as a state locked in perpetual conflict with its neighbour. That episode boosted India’s image as a responsible nuclear power committed to the rule of law and to peaceful diplomacy even in the face of grave provocation.

Today, however, that image appears increasingly compromised. India’s tacit financial and diplomatic support to both Russia and Israel in their ongoing military campaigns stands in direct contradiction to its professed advocacy of peace.

By purchasing discounted Russian oil for months, and by maintaining and expanding arms trade with Israel despite allegations of genocide, India has pursued strategic gain largely accruing to crony capitalists, defended as serving national interest, while delivering negligible benefit to ordinary Indians, at the cost of ethical consistency.

These decisions, framed as pragmatic policy choices, have the effect of legitimising state violence and undermining India’s credibility as a nation that claims to uphold international law, human rights, and dialogue over force.

The same incoherence marks India’s recent outreach to the Taliban. The decision to host the group’s foreign minister and to announce the upgrade of India’s “technical mission” in Kabul to full embassy status—even as the Taliban remains internationally ostracised for its repression of women and its links to terror networks—represents a jarring reversal. When a government that vows to oppose terrorism engages publicly with a regime steeped in extremist violence, one wonders where India truly draws the line.

This episode is emblematic of a broader erosion. The pillars of India’s foreign identity are fraying. India is courting every major power in pursuit of strategic autonomy, while seeking to incur minimal cost.

It wants the status of moral leadership without the burdens that such leadership entails; it wants to assume the mantle of Global South champion without the act of speaking truth to power. While opportunism may buy short-term advantages, in the longer term it erodes trust and influence.

This pattern of calculated pragmatism cloaked in righteous rhetoric raises a fundamental question: What does India actually stand for in the world today?

The answer emerging is: for strategic ambition, economic expediency, pole-positioning in a multipolar world—but not for moral clarity, ideological conviction, or consistent leadership.

If India continues to define its foreign policy in those terms, it will not only lose the high ground it once occupied, but also increasingly find itself isolated and regarded as transactional.

To raise its international standing again, India must ask itself: Can it live up to the claims it makes? Or will it continue to engage in diplomacy driven by optics rather than substance?

The world does not need another power that says noble things and acts opportunistically. It needs one that asserts principle, consistently and with the courage to bear its costs. If India is to regain the weight of its early-republic identity, it must seriously acknowledge the hollowing out of what it once stood for, and begin the hard work of living up to it.

(The writer is an assistant professor with the Department of Professional Studies, Christ University, Bengaluru)

(Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.)