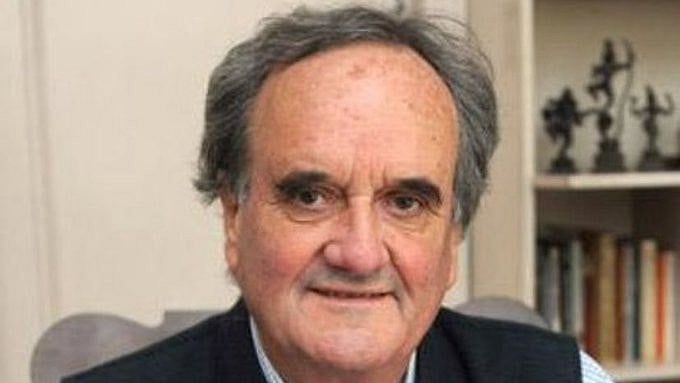

Mark Tully.

Credit: X/@NickBryantNY

That day, in a gentle drizzle, I stepped out to find an address in New Delhi’s Nizamuddin East. As I walked through its quiet lanes, an unspoken excitement stirred within me. I was on my way to meet a voice through which India had spoken to the world.

This meeting had taken nine long months to materialise. It was not merely an interview; it was the fulfilment of a deeply cherished personal dream. Precisely at 3 pm, I rang the bell. The door opened to Gillian Wright, who welcomed me warmly inside. Beside her stood their pet dog, wagging its tail affectionately.

“Satish is here,” Gillian called out as she led the dog indoors. I settled into a sofa in the drawing room. The space felt like a living museum—a house that seemed to breathe history. And within it lived a man who was history itself.

Sir William Mark Tully walked up to me, shook my hand gently, placed an arm around my shoulder, and said warmly, “Today I have kept aside two full hours just for you.”

Sitting opposite me was the former chief of the BBC’s New Delhi Bureau, a role he held for nearly three decades—a journalist who had reported India’s defining moments to the world. Though well into his eighties, his eyes sparkled with youthful curiosity. Within minutes, his gentle words dissolved all formality. I felt I was speaking not to a legend, but to an old, trusted friend—a godfather of sorts.

Born in Kolkata to a British civil servant, Mark spent much of his childhood in Darjeeling, attending a boarding school. At 19, he was sent to England for higher studies. At Trinity Hall, Cambridge University, he studied theology. After two semesters, however, he realised that the Church’s rigid rules regarding personal life conflicted with his own beliefs. With remarkable honesty, he chose to abandon that path.

A small notice on a BBC notice board later altered the course of his life. It invited applications for the post of assistant administrative officer at the BBC’s New Delhi office. Mark applied. During the interview, he was asked to count in Hindi—Ek, do, teen… das. That was enough. After completing radio broadcasting training in London, he arrived in Delhi as the BBC’s Hindi correspondent. In those days, radio was the most trusted medium, and Mark believed that absolute trust was the bedrock of journalism—and of his career.

He spoke at length about defining moments in India’s political history: the wars of 1965 and 1971 with Pakistan, Indira Gandhi’s rise, and, most significantly, the Emergency of 1975. Foreign media organisations were pressured to sign government declarations. Mark refused. As a result, he was expelled from India and given just 24 hours to leave. He returned to England unwillingly. When the Emergency ended, he returned—this time as chief of the BBC’s New Delhi Bureau. Over the next two decades, he witnessed and reported almost every turning point in modern Indian history.

Mark reported on Mother Teresa’s Nobel Peace Prize in 1979, Operation Blue Star, Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992—covering these momentous events with rare proximity, courage, and integrity. Repeatedly, the BBC offered him senior positions in other countries, but he consistently declined. He would say he had no objection to being transferred—but he would not leave India. If forced, he would resign.

Eventually, in 1993, Mark resigned at the age of fifty-nine. By then, his wife, Margaret, and their children had grown distant from him. Though legally married, their lives had taken separate paths. Gillian Wright—a writer and journalist—had by then become his life partner. From fifty-nine to eighty-five, Mark wrote extensively, anchored radio and television programmes, and continued to present India’s soul to the world with honesty

and empathy.

During our long conversations, Mark shared countless political anecdotes. Between stories, memories of Delhi flowed effortlessly—morning walks in Lodhi Garden, tea at Azad Bhavan, browsing bookshops in Khan Market, evenings at Connaught Place, and late-night South Indian meals. Each memory surfaced with childlike affection.

As we concluded our meeting, Mark clasped my hand firmly and said, “Good things in life take time.” He added that had we not met, we would have lost a valuable friendship—one that would have remained unrealised forever.

A few months later, at my invitation, Mark visited Bengaluru and spent four days with me. He interacted with university students, attended a book launch, and met old friends. On the day of his departure, as he was driven to the airport, he spoke quietly about his bond with India. India, he said, was not merely a country but a way of life. Had he not come to India, his life would have felt incomplete. India was his karma bhumi, and merging into its soil, he believed, would be his destiny. He merged with it precisely as he wished.

When Mark passed away on Sunday, January 25, 2026, I was deep inside the Western Ghats, far beyond the reach of the civilian world. When I finally emerged from the forest and switched on my mobile phone, the news struck me with a force I was unprepared for. But, for me, Mark has not gone anywhere. He lives on—in my heart and everywhere around me.

I can stand on the summit of Everest and proclaim to the world that Mark Tully was the one journalist who understood India more deeply than anyone else—and reported on it without agenda or bias. He is eternal.

Sir William Mark Tully lives on through his stories, books, and timeless wisdom. Who could ever forget his warmth—the firm handshake, gentle hug, soft smile, and sparkling wit that lit up every conversation?

(The writer is a storyteller, novelist and a non-working Journalist)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.