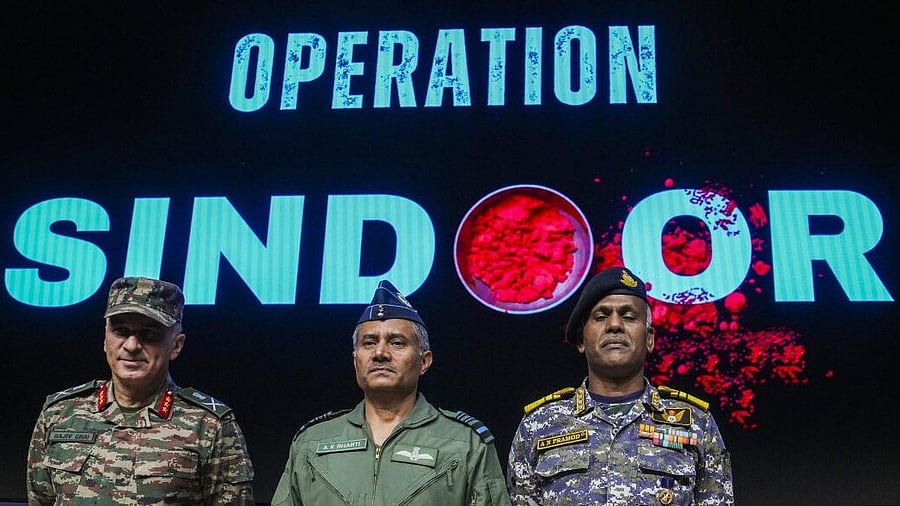

Director General of Military Operations (DGMO) Lt General Rajiv Ghai with Air Marshal AK Bharti and Vice Admiral AN Pramod during a press conference on 'Operation Sindoor', in New Delhi.

Credit: PTI File Photo

The nation stands with the Prime Minister in saluting the defence forces and condemning the barbaric terrorist killings in Pahalgam – an act that prompted India to strike deeper into Pakistan than it has in five decades. The widespread support for the Indian response reflects a strong national resolve to find terrorists wherever they are and bring them to justice. Yet, this resolve risks devolving into an echo chamber of self-congratulatory noise that can obstruct the deep analysis needed to fully understand how the theatre of war unfolded.

While some of India’s objectives appear to have been met, it is premature to call Operation Sindoor an unequivocal success. But even if the operation achieved limited goals, the lessons it offers are vast. We now have a minefield of data – ranging from political groundwork and diplomatic engagement to planning, strategy, operational challenges, and rich battlefield data on the performance of high-tech military hardware and cutting-edge platforms.

The next battle will be won not only on the military front but, more importantly, on the political front, where major decisions on war are taken. Learning is not always easy. At the highest political levels, it challenges the very playbook that brought us aggressive rhetoric and roaring war cries – even at election rallies – while showing little of that quiet, difficult work needed to build international support in times of crisis. This requires fostering an environment that encourages hard questions, grounded in humility, integrity, and curiosity, none of which is helped by a self-gloating that tends to shut out critical inquiry.

To build national unity, political parties across the spectrum must be brought together through trust-building measures – not through election-style attacks on the Opposition. In this context, the prime minister’s decision to skip the all-party meeting on April 24, just two days after the Pahalgam killings, was a misstep. All political leaders, including the leaders of the opposition in the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha, were present. That absence echoed an old playbook. However, the government’s recent decision to send all-party delegations to international capitals suggests a change in outlook. Still, the controversy around Shashi Tharoor – added to the list without Congress’ nomination – was an avoidable provocation. Old habits will die hard, and with them, valuable lessons are not learned. The Congress has accused the BJP of playing games, leading to mistrust and poor political relationships – at a time when deep unity is crucial.

Another important lesson concerns the way information has been rendered meaningless. In the fog of war, it is wise to discard most external claims and counterclaims about what went right or wrong – especially as they are amplified by shrill media anchors and self-styled ultra-nationalists pushing largely unverified narratives. Such is the phantasmagorical volley of claims that the government might be embarrassed, so much so that the pro-government media has rendered itself useless to the very masters it seeks to serve. Like customer reviews on an e-commerce platform, which gain credibility by showcasing both praise and criticism, media credibility depends on accommodating diverse opinions. A space flooded by one-sided commentary ultimately undermines the very side it champions. These are elementary lessons that must be relearned.

War is the last resort. This has long been India’s position, reiterated by the Prime Minister himself. In 2022, at Kargil, he said, “India has always viewed war as the last resort, but the armed forces have the strength and strategies to give a befitting reply to anyone who casts an evil eye on the nation.” But when this last resort, the brahmastra, is exercised, it risks losing its potency. It cannot be deployed again in the same way. A more limited action would appear weak, while a stronger one risks rapid escalation and unacceptable consequences. This matters, especially now that a ceasefire was announced not by India or Pakistan but first by US President Donald Trump. The implication of this will take time to assess.

Meanwhile, some political responses circulating in WhatsApp groups must be avoided – one message claimed that a “full war” would be possible only if the BJP wins 400 seats. Such statements are dangerous and disrespectful. Terror attacks and war are not issues to be used to seek votes or parliamentary seats. These overzealous remarks by party sympathisers only harm the cause they claim to support.

It is also worth noting that Trump, in his ceasefire announcement, equated India and Pakistan – erasing years of genuine diplomatic efforts to de-hyphenate the two nations. This is unfortunate. India and Pakistan were born at the same time but have taken vastly different paths: India as a secular democracy and rising economic power; Pakistan as a failing State that faces economic uncertainty. The re-hyphenation undermines India’s growing stature and diminishes its standing on the global stage.

Finally, the Pahalgam killings expose the hollowness of the government’s claim that peace would return to the Valley after the abrogation of Article 370. That promise clearly has not borne out, as indeed many had warned. It is time to ask hard questions: How do terrorists strike with such ease? Where were the security forces? What is the level of intelligence? And why are there no consequences, no heads rolling when such killings recur? The killers of innocent people in Pahalgam still roam free.

There are many lessons from this short war – but they will be visible only to those willing to challenge themselves and ask the difficult questions.

(The writer is a journalist and faculty member at SPJIMR; Syndicate: The Billion Press)