The first essay in a three-part series underlines an erosion of the nation’s inclusive foundations, but argues that its institutions are built to resist breaches.

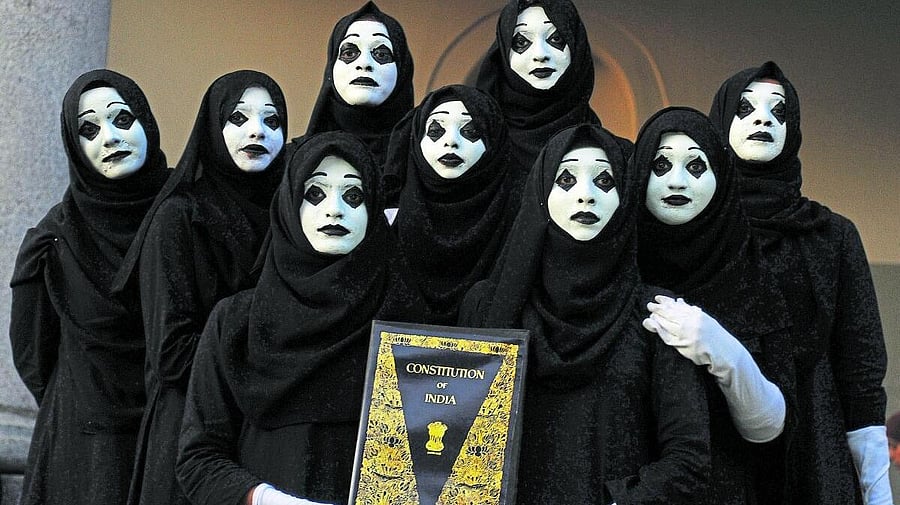

DH Photo by Pushkar V.

Subramanian Swamy, the BJP’s former Rajya Sabha member, was involved in studying the draft alternative Constitution. He told Frontline, in 2017, that the BJP leadership actively considered working on this draft, but he dissuaded them from going ahead. “For one, I told them that the existing Constitution has enough elements of a Hindu Rashtra. I told them that we already are a de facto Hindu Rashtra and there is no need to become a de jure one. In my opinion, adopting a new Constitution is not possible unless there is a revolution. Besides, our Constitution already has enough of Hindutva in it,” he told the correspondent. He said this was his response when he and a few eminent lawyers were asked about their opinion on adopting a new Constitution. “This was shortly after I had joined the BJP [by merging his Janata Party with it at the time of the 2014 Lok Sabha election]. Swamy said that after the government was formed, he was asked for his opinion on this issue. The draft alternative Constitution had been prepared by “some Vidyarthi Parishad member” in 2000-01, but that document was discarded for now, he said.

The suddenness and swiftness with which the Gen Z protests in Nepal last September took an extremely violent, destructive turn and blew the lid off the political regime has surprised everyone. Recent, similar upheavals in our neighbourhood include: the overthrow of the Sheikh Hasina government in Bangladesh in 2024 and the meltdown of the regime in Sri Lanka in 2022. In 2021, a coup d’état replaced the democratically elected government with a military junta in Myanmar, and an insurgency and civil war ensued. Two decades earlier, a Maoist-led decade-long insurgency and civil war in Nepal led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of a republican constitutional democracy. Even earlier, in 1971, a civil war led to the secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan.

On the other side of the globe, Donald Trump has, from Day One of his second Presidency as he had promised, effected drastic changes across a wide range of domestic and foreign policy areas aimed at radical transformation, revolutionary even, in the American nation. Also noteworthy is that Trump returned to power after being indicted for the January 2020 attempt to overturn the result of the Presidential election, which he had lost. This was surprising not merely because it occurred in what was considered a centuries-old, stable democracy whose last major crisis was more than 150 years ago. But also because it was generally believed that in the post-Second World War period, the advanced Western nations were immune to the kind of instability and radical transformations that have characterised the Global South and the less developed countries of Eastern Europe.

For better and worse, the radical changes in those other countries in recent decades include: The revolts of the “Arab Spring” in the early 2010s, which brought down some dictatorial regimes, and the attempts, mostly unsuccessful, at setting up stable democratic governments in the aftermath. The slow but progressive authoritarian Islamisation of Atatürk’s secular, modernist Turkey, and the breaking of the back of its guardians, the military, by President Erdoğan. Going back a few more decades, there have been: The disintegration of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the erstwhile Soviet Union. The violent overthrow of the secular dictatorship of the Shah and the establishment of an Islamic theocracy by a mass upheaval led by Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran. Besides, there are the many political instabilities and military dictatorships in Latin American countries and in the newly liberated nations of Africa and Asia, after they established independent, nationalist governments following the overthrow of Western imperialist domination, in the aftermath of World War II.

The recent developments in our neighbourhood, particularly, have once again focused analysts’ attention on the remarkable stability and continuity of Indian constitutional democracy. Despite being extremely contentious, unruly, and at times violent, Indian politics and public life have been contained, barring the interregnum of the 21-month Emergency, within the overarching constitutional democratic framework established after Independence. In contrast with what Trump attempted, the losing parties have accepted defeats in State and national elections. Even Mrs Indira Gandhi relinquished power after losing in the general elections held under the Emergency. In this article, I aim to explore what explains this phenomenon and identify its contributing factors.

Divisions and exclusions

There are doubtless critics who will question my characterisation, especially with reference to the rise to dominance of the Narendra Modi-led BJP in Indian politics and society. They cite many developments and features to argue that the Modi government has transformed India into a majoritarian or illiberal democracy or electoral autocracy, that the BJP-RSS has captured the Indian State, that there has been “democratic backsliding”, or even that there is an undeclared Emergency. The construction of the Ram temple in Ayodhya on the same land where the Babri Masjid once stood and was earlier demolished, after securing a Supreme Court verdict. The lynchings of Muslims by mobs linked to the Sangh Parivar and kindred organisations, mostly on suspicion of cow slaughter. Illegal punitive demolitions of constructions belonging to, and evictions and deportations of Muslims. The various forms of continuous harassment of Muslims, and to a lesser extent, Christians.

The passing of the Citizenship [Amendment] Act (CAA), which discriminates against Muslims and some other minorities. The campaign and laws against alleged induced religious conversions under slogans like “love jihad”, “rice bag”, etc., and “urban naxals” aimed at Muslims, Christians and leftist intellectuals, activists and protestors. Detentions of some leftist and Muslim activists and protestors for long periods, with bail given to some of them after considerable delays. Hindutva activists accused of terror were let off by the courts. The policing of social conduct, particularly of women, and diverse forms of attacks on inter-religious, especially Hindu-Muslim, gender relationships. The reduction of Muslim representation in positions of power and influence, such as legislatures and ministries. Forcibly pushing suspected illegal Muslim immigrants into Bangladesh. The attempt to rewrite history from an RSS-BJP interpretation of the “glory” of the Hindus, especially in ancient times, and the exclusion and/or denigration of the role of Muslims historically. Reinterpreting modern science, including medicine, Indian history and culture from a Hindutva perspective, and attempts to effect changes in the medical, education and other systems. Replacing Muslim names with Hindu ones. Giving a Hindu religious colouring to all aspects of public life.

The abrogation of Article 370 and continuing Central intervention in Jammu and Kashmir, bypassing the democratically elected State government. The extra-judicial encounter killings of suspected criminals. Suppression of criticism of and protests against Modi, particularly. The various methods employed to suppress and bulldoze the Opposition in Parliament and outside, including the refusal to allow debate on key issues. The use of Central investigative agencies against Opposition leaders, especially in States where they are in power, to discredit them, to subdue them, to cut off their sources of political funds, and even to bring them into the BJP or NDA fold. The revanchist rhetoric against Pakistan for its proxy terror attacks in India.

Furthermore, certain statements and actions by the NDA Government and its leaders have raised suspicions regarding their intentions and plans. There is the warning from the Prime Minister in his Independence Day Speech last year about the national security risk arising from “democratic imbalance due to infiltration and illegal migration in border areas” and the launch of a High-Powered Demography Mission to address it.

Subsequently, RSS leader D Hosabale, less constrained perhaps because he does not hold a government position, has added “conversion, and higher rate of growth in some communities” as reasons for this alleged imbalance. Taken together with the passing of the CAA in 2019, the statements to extend the National Register of Citizens (NRC) from Assam to other States across the nation, the revised norms for voter registration in the rushed SIR in the run-up to the Assembly elections in Bihar, the extension of SIRs to other States, and the unprecedented, very considerable delay in the national Census without giving any reasons – all these have heightened anxiety. Do these presage attempts to make Muslims (and possibly Christians) second-class citizens, if not disenfranchise them altogether?

In their defence, the BJP-RSS argument would probably be that the NDA Government is only attempting to identify and send back illegal immigrants, and not Muslims who are Indian citizens; that they are trying to reverse “appeasement”, not fair and equal treatment; that they are only trying to prevent religious conversions through inducements, fraud and force, not genuine change of faith; and so on.

In addition to the fact that there is much truth in the above charges, even if sometimes exaggerated and one-sided, there are other serious violations of democratic norms, procedures, and institutions. On certain occasions, constitutional authorities and institutions have been less than impartial, if not blatantly partisan, favouring the ruling BJP and Prime Minister Modi. A recent example is the failure of the Election Commission to halt the disbursements through direct cash transfer in the Mukhyamantri Mahila Rojgar Yojana, which was launched just ahead of its announcement of the schedule for the Bihar Assembly elections by Prime Minister Modi instead of Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, as earlier announced. Not only was the disbursement made just days before each of the two phases of polling, but there was also a promise of substantial additional disbursement after six months. Media reports have noted that the Election Commission suspended disbursements from long-standing welfare schemes during elections in Tamil Nadu in 2004 and 2011, on the grounds that this violated the Model Code of Conduct. A PIL filed at the Patna High Court alleging that the scheme was used to influence voters after the Model Code of Conduct was in force failed to halt the disbursement. Opposition protests to the same effect were also of no avail.

Pointers to the past

Needless to add that such examples are hardly the exception. However, many, if not most, of them arise from weaknesses in the Constitution itself or from the practices of earlier governments, which have paved the way for subsequent governments to exploit them for their very different purposes and ends. One example is the encounter killings of leftist extremists and insurgents, especially in the border states of northeastern and northern India. Other examples include the evisceration of Article 370 from Nehru’s time onwards, and the use of Central investigative and intelligence agencies against Opposition leaders, a practice Indira Gandhi had begun and often used. On some points, Modi has implicitly claimed that he is more democratic than earlier Congress Prime Ministers. For example, he has charged that those Prime Ministers had misused Article 356 for partisan ends by dismissing democratically elected Opposition State governments 90 times. He could also, justifiably, claim that he has not superseded senior Supreme Court judges, as Prime Minister Indira Gandhi did in the 1970s, in an attempt to control the judiciary. Subsequently, after imposing the Emergency, she completely subjugated the judiciary.

Conversely, when the founders and their successors adopted and established democratic norms, practices, and institutions, those precedents often became entrenched and were much more difficult to violate. Despite Modi’s three successive electoral victories in the general elections and many wins in the States, constitutional democracy, in its electoral and party-political aspects at least, continues not merely to survive but thrive. Elections to State and national legislatures are held on time, Opposition parties are vociferous and unyielding in and outside Parliament and State legislatures, results are honoured, and transitions to the winners are smooth and uncontested. Considering that one of the BJP’s senior-most leaders, L K Advani, had, early in Modi’s tenure as Prime Minister, said that he did not think another Emergency was unlikely because those in power [that is, Modi] lacked commitment to democracy, this is an amazing turnaround. The question arises, what accounts for it?

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.