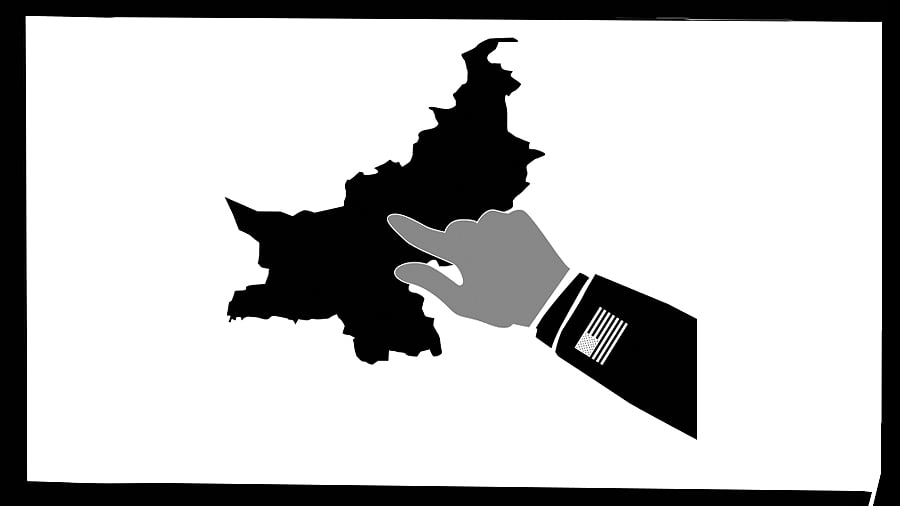

DH ILLUSTRATION

The subcontinental word bichauliya could be translated to a mediator at best, or a wheeler-dealer, at worst. In the nativist sense, it is afforded the perception of an insincere salesman who curries favour both ways. For long, Pakistan has played this unique role of a middleman amongst the unlikely and the warring lot. But it is also a sovereign skillset that naturally elicits duplicity as a collateral perception. It runs the risk of getting viewed suspiciously, as an oddity that can run with the hare and hunt with the hound, seamlessly. Pakistan’s complicated relationship with terrorism – both as a perpetrator and a victim – is one example of the consequences of playing the dangerous game of the middleman.

The double-gaming abilities of Pakistan came to the fore in the early 1960s when, as a member of avowedly anti-communist alliances like CENTO and SEATO, Islamabad was separately able to stitch the Sino-Pakistan Agreement in 1963. Despite being a firm US ally, Pakistan surrendered over 5,000 km of claimed territory to China and made a strategic common cause against India. The US also didn’t make much of the Pakistani largesse towards the Chinese, as Washington had little love lost for Delhi during the Cold War era. The settlement of borders between China and Pakistan also helped build the Chinese narrative of supposed Indian intransigence with regard to its territorial disputes with China, as also, sullying the Kashmir territorial issue by recognising the areas that were parts of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir as belonging to Pakistan.

India-wariness became the principal bind for the unnatural “all-weather” friendship that ensued between Islamabad and Beijing, as it had no civilisational, cultural, or ideology-based rationale attached to it. Despite the local tumult, upheavals, and intrigues within the domestic politics of Pakistan or in the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party, the reciprocal bonhomie towards each other remained rock-solid.

Leveraging the schism between China and the USSR, the redoubtable US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, invoked the intermediary services of Pakistan in the ‘Ping Pong Diplomacy’ to engage with China. As part of the moral compromise, Kissinger accepted Pakistani excesses in East Pakistan (later, Bangladesh) as the price for its midwifing services: “To condemn these violations publicly would have destroyed the Pakistani channel, which would be needed for months to complete the opening to China.” It was a knowingly amoral and transactional approach from both sides, where the Pakistanis extended a middleman service and were paid back with strategic support, however unscrupulous.

This template of Pakistani middlemen was perfected by the covert role it played along with the US through the 1980s in Afghanistan. ‘Operation Cyclone’ was amongst the largest operations launched by the CIA along with the Pakistani ISI, to arm, train, and finance the mujahideen movement in bleeding the then Soviet Union. Pakistani dictator General Zia-ul-Haq was knowingly supported as he provided invaluable conduit services. That these Pakistani middleman services were to ultimately breed the sort of toxic religious extremism and terror nurseries that continue to haunt the region is often forgotten. The injection of religiosity (later morphing into the Taliban phenomenon), the rise of uncontrollable militant groups, and triggering armed insurgency in the Kashmir valley can be traced to Pakistan’s middleman services on behalf of the US and rich Sheikhdoms. Later, as one of the rare nations to legitimise the Taliban government in its first husting (1996-2001), Pakistan gave away its hand in shaping the narrative.

Fickle friendship

Forever the unreliable and fickle partner to any side, Pakistan incredulously joined the War on Terror against its own protégé regime in Kabul. George Bush’s threat, “You are either with us or against them”, led to yet another flurry of military weaponry, aid, debt relief, and diplomatic support a la the 1980s, and yet again, Pakistan was willingly the middleman the US used to control the Afghan mujahideen. As always, the Pakistanis were less than sincere and often frustrated the US with their double-speak.

The discovery of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad became an example of how each side distrusted the other, but retained the transactional façade of necessity to ensure that things seemed as normal as realistically possible with Pakistan. Optics of the DG-ISI rushing to Kabul on the abandonment of the US forces from Afghanistan and sipping tea with the ragtag Taliban militia became the picture of the double-game wherein the Pakistanis always kept multiple channels open with the so-called “friends” and the “enemies” alike, as such nomenclatures were always interchangeable for Islamabad.

Donald Trump, in his first tenure, had openly tweeted about the Pakistanis, “They have given us nothing but lies & deceit, thinking of our leaders as fools. They give safe haven to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan, with little help. No more!” He had even tightened the support whilst courting India on the rebound. But like the Pakistanis, Trump himself is an incorrigibly unreliable leader who can stoop to any level of transactional bargain (read, bullying or coercion) to have his way, even with so-called “friends”.

After his supposed overtures to India, the president has had no qualms in imposing a 50% tariff on Indian exports whilst showing an unbelievable sense of accommodation and compromise on trade with Pakistan, simultaneously. The “middleman” attraction of Pakistan may have been secured for its stated commitment to keep the troublesome likes of the anti-US Imran Khan incarcerated, or more importantly, for potentially opening the back-channels of communication with the latest nemesis, i.e., Iran. Yet again, the middleman utility with Iran (or even Afghanistan) is dangled by the Pakistanis, and Trump has no qualms in dropping its equation with India as quid pro quo. It is a dangerous appeal because it is need-based. Pakistan has been used and abused many times before, but for now, it holds the middleman advantage.

(The writer is a former Lt Governor of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Puducherry)