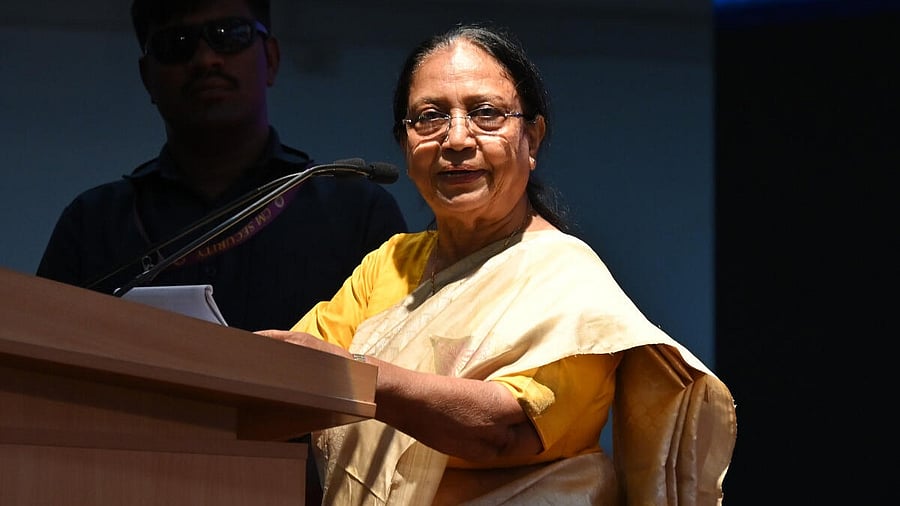

Booker Prize winner Banu Mushtaq talks during the felicitation at Vidhana Soudha, Bengaluru on Monday, June 02, 2025.

Credit: DH Photo/Pushkar V

I first met Banu Mushtaq, the 2025 International Booker Prize winner, in the revenue court of the deputy commissioner, Hassan. I was presiding over it, and she, the lawyer, was appearing for the clients. We became family friends. What was remarkable about her was she always appeared for the poor and the indigent clients, mostly women.

Women carry a disproportionate burden of religion, culture, and tradition. They live in a world of norms and traditions created by men. And any dissent, a minor rebellion, is put down with force, and the justification for such repression is often found in religion, culture, and tradition. The norms, mores, and traditions, said to be steeped in religion, are written by men, advocated by men, and interpreted by men, sitting as maulvis, pandits, or priests. It therefore takes extraordinary courage for women to speak their mind and beg to differ.

Banu Mushtaq has given voice to the women who think differently, rebel, and dare to dream but suffer in doing so. Mehrun, the protagonist in the story Edeya Hanate (the title of the book in English, Heart Lamp, for which the prize was given), decides not to put up with the insult and indignity of an affair her husband was having with a younger woman. She walks out of her husband’s house in Chikkamagaluru and travels to Hassan, to her father’s house. She had great pride in the strength of her brothers, and she expected empathy from the home where she was born. Instead, she receives a hostile reception and is promptly taken back to her husband’s house. The men—her father and her brothers—turn out to be not so brave after all. Life, society, and tradition have made them cowards. They worry about their reputation. One brother says, “Why didn’t you die by burning yourself before dishonouring our family by walking out on your husband?” This classic contradiction between societal norms and individual freedoms of the women characters is a recurring theme in most of Banu’s stories.

Banu Mushtaq, a member of the Bandaya Sahitya movement, had the courage to write the stories of Muslim women carrying the burden of religion, tradition, and notions of honour that men create. Muslim women who dare to dream, dare to think differently, and try to act on their thoughts and dreams. Stories of women whose dreams are ultimately crushed by a society that calls for a sacrifice from women and lets the men go scot-free.

These stories may have come out of Banu Mushtaq’s interaction with her society and the experiences of being a lawyer to poor, underprivileged clients—she represented the poor before the courts of law. But these are stories with universal appeal—stories that people of various cultures and religions around the world can relate to, connect with, and empathise with. It is therefore a significant milestone that such experiences, born out of Muslim households and written in one of the world’s oldest languages, have now received a global platform, thanks to the International Booker Prize.

Things can change if we shine light on them. Banu Mushtaq has given voice and now a global platform to the Mehruns, Hasinas, and Jameelas of Muslim society. But make no mistake: the plight of these women is not unique to the Muslim community; they are universal, and we can find such stories in all societies; patriarchy is the monopoly of no single religion. The patriarchal judgements delivered by the maulvis in jamats, for example, are not very different from those at the khap panchayats or similar forums of other communities.

What is significant is that Banu Mushtaq, a woman and a Muslim living in a conservative Muslim society, has dared to write stories that challenge traditional norms and the interpretation of religion by maulvis, who are schooled to uphold patriarchy. Her work focuses on individual women’s rights to emancipation, autonomy, and control over their bodies and eventually their destinies.

Literature is not merely stories that some write and others read at their leisure. It can be an act of rebellion and dissent; it is a search for truth. As Milan Kundera, the Czech Nobel Prize-winning novelist, said, “To be a writer does not mean to preach a truth; it means to discover a truth.” Banu Mushtaq, through her literature, has uncovered the truth of women’s lives in conservative, patriarchal societies.

(The writer is former ACS to chief minister of Karnataka)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.