Photos: Games of Emergency by Abu Abraham

In a utopian society, political cartoonists would be redundant and jobless. The task of the political cartoonist is to hold a satirical mirror to the oddities and absurdities of the society. The ridicule and laughter invoked by a political cartoonist is not an end in itself. Rather, it functions as a tool through which the readers/viewers look critically at their own society and its afflictions, becoming critical and subversive rather than passive observers. A society where cartoonists work with no restrictions can only be a perfect democracy. But can such a perfect democracy ever exist? What happens when restrictions are imposed on the expression of discontent? While that situation begs to be treated by cartoonists, their metaphorical tongue (the drawing pen) is tied. A glimpse into the cartoons of the Emergency Years (1975-77) in their historical context sheds light on the power of cartoons and the tightrope that cartoonists walked between the necessity of expression and the threat of being locked up.

“The President has proclaimed Emergency. There is nothing to panic about”, said the voice of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on the radio exactly 50 years ago in the wee hours of June 26, 1975. There were hardly any newspapers delivered that morning since electricity to publishing houses had been interrupted the previous night to prevent the press from reporting about the Emergency. A judgement pronounced by the Allahabad High Court on June 12 that year had held the PM guilty of electoral malpractices in the 1971 general elections. The 12-day stay order on the judgement saw the declaration of the Emergency the projected aim of which was to protect the nation against ‘internal disturbances’. At the same time, the opinion that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had spun this tale to give herself an opportunity to safeguard her position as PM was also popular and gaining momentum. By the time the general elections took place next in 1977, this opinion had gained enough strength to result in Indira Gandhi’s electoral defeat. While blank editorials, satirical obituaries and the like in the newspapers contributed to this subversive impact, political cartoonists are the real protagonists of this story for trying to take censorship by its horns.

Cartoonists Abu Abraham and R K Laxman, working with two different English-language national dailies at the time, persisted in spite of the pre-censorship order that was in place on and off through the 21 months of the Emergency. This order entailed that everything—articles, cartoons, obituaries, advertisements and others—had to be passed by the Chief Censor’s office before publication. Cartoonists have often highlighted the arbitrariness of the Chief Censor’s office, but it is evident that their consistent efforts tested both the Censor’s efficiency and elasticity. One of Abu’s favourite techniques was to use linguistic quips: puns, twisting of words, oft-quoted phrases, or proverbs to push them to have a satirical effect. A fitting example of this technique is this cartoon that was published on December 31, 1975:

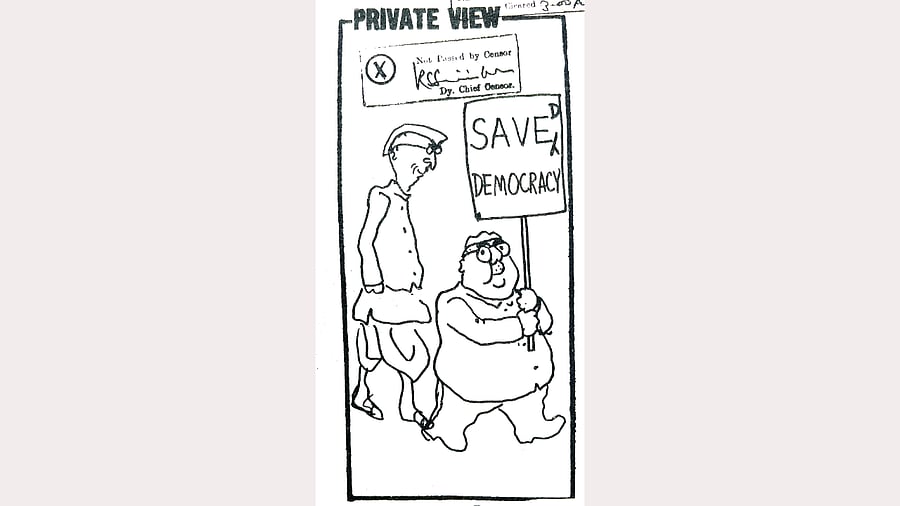

We see Abu’s two stock figures (the short, stodgy worker and the tall, lean worker of the ruling party) celebrating as the caption quips on the familiar saying “Ring out the old, ring in the new” such that it now reads: “Ring out the old, ring in the old”. The contextual meaning becomes apparent as we read the relevant headline below: “Congress Wants Lok Sabha’s Life Extended”, which in effect means that the ruling party will stay in power by deferring general elections to a later date, a power vested unto themselves by invoking Article 352. Hence, the ruling party workers are celebrating ringing out the old and ringing in the same old, invoking satirical laughter. When Abu uses the same technique to comment even more directly on the attack on the spirit of democracy, the cartoon does not escape the censor’s net: We see the stock figures carrying a placard that was to have read “Save Democracy”, but a simple change has been made using a caret such that it actually reads “Saved Democracy”. The message is clear: democracy, which was to be saved for the masses, has been saved away from the masses themselves. The time stamp on the cartoon also shows us the urgency with which it was “Not Passed by Censor”, as it was received at 2:50 pm and rejected at 3:00 pm. This brings to mind a contrast between the infamous inefficiency of the Indian populace before the declaration of the Emergency and the immaculate efficiency of the Censor’s own office during the Emergency. (Abu published this cartoon immediately after the Emergency was

lifted in his little anthology titled Games of Emergency, a pun on the phrase

“gains of Emergency” often used by the government.)

In fact, contrast was used as an essential technique by R K Laxman. Meaning was conveyed in Laxman’s cartoons sometimes through a contrast between the text and the image, at other times between an ideal democratic nation and the actual state of affairs in the country, and sometimes both simultaneously. Irony and humour often became a shield for the satire the cartoonist levelled. In a hard-hitting editorial cartoon that escaped the clutches of the Chief Censor and was published on December 11, 1975, Laxman’s iconic Common Man figure is seen lying face downward with his head buried under a newspaper. Only his characteristic attire (checked coat, dhoti, and boots) is visible as his head is hidden under the headlines on the newspaper’s front page: “FINE”, “GREAT”, “VERY GOOD”, “PLENTY”, “VERY HAPPY”, “VERY ROSY”, “MARVELLOUS”. This becomes an iconic satirical comment upon the censorship prevalent in the country, as the rosy text directly contrasts with the image of the despondent common man buried under the weight of propagandist news articles that seem to be far from his lived reality. In another cartoon published on February 14, 1976, we see a few beggars approaching a car, perhaps at a traffic signal, asking for alms as the driver replies, “Go away, my dear man—didn’t you read in the papers there are no more beggars?” The ironical contrast between the newspaper image of the poverty-free country and the reality of the street is more than evident.

The strategy of contrasting the ideal with the actual and the text with the image was surely not a foolproof one. Many a time, Laxman’s cartoons were not cleared by the Chief Censor’s office. Laxman recalls, in an article published in 1989, being told by an insider the perplexity of the censor officers when a Laxman cartoon was received:

“When my cartoon came under their scrutiny, the censor was in a fix, I was told. If he understood a cartoon and it tickled his wit, he immediately banged the rubber stamp ‘Rejected’ on it on the basis that something that made people laugh might be an anti-government reaction. But if the cartoon showed no scope for laughter at all, it got the reject stamp even so because it might harbour pernicious intentions.”

Nonetheless, the persistent publication of cartoons in newspapers presents a constant counter-narrative to the one offered by the government through the censored articles and bans. Every time a cartoon slips through the cracks, it broadens the perspective of the readers; they may not be passive recipients of news reports anymore. Satirical cartoons train the readers in reading between the lines and subversively looking for counter-narratives, thereby strengthening the democratic spirit which is marked by constructive critique and questioning. How freely satirical political cartoonists function in a society is in fact a litmus test for the robustness of the democracy.

(The writer teaches liberal arts at Vidyashilp University, Bengaluru)