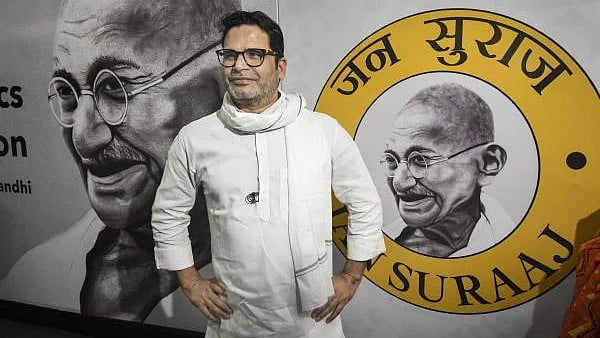

Political strategist Prashant Kishor

Credit: PTI Photo

The beauty of democracy lies in its ability to accommodate new socio-political experiments. Political philosopher Adam Swift once said democracy is like ‘motherhood and apple pie’—something universally desirable, even if imperfect. In contrast, other political systems such as authoritarianism, monarchy, or one-party rule are opaque and bound by rigid belief systems.

Contemporary Indian democracy is witnessing a new experiment -- what might be called start-up politics. The term is not used pejoratively but to attribute a characteristic to this attempt. This start-up model is best exemplified by Jan Suraaj, led by political strategist Prashant Kishor in Bihar’s crowded political field. It is a top-down experiment built on the power of technology and a structured narrative.

In recent years, political yatras have proliferated across political parties and ideologies. Amid these, Kishor’s Jan Suraaj walked through 2,697 villages and 235 blocks across Bihar. The purpose is to forge an emotional connection with ordinary people and offer an alternative to existing political choices.

The experiment differs from others in three ways.

First, Jan Suraaj presents itself as a top-down mission to transform Bihar, leveraging Prashant Kishor’s professional experience as a political strategist who has reshaped the landscape of India’s political consultancy.

Second, unlike the Aam Admi Party, which rose from issue-based movements, Kishor’s outfit eschews mass protests or revolutions. Instead, it promises a detailed blueprint for Bihar’s development and seeks to convince voters to buy into it. The movement is driven by a mix of remorse for Bihar’s state of affairs and pride in Bihari asmita.

Third, as a new organisation, Jan Suraaj is unburdened by the baggage of mainstream parties. It is also raising issues long ignored by mainstream parties—palayan (migration across age and social groups), the need to focus on service over industry given Bihar’s geography, reforming primary education, and dismantling bureaucratic autocracy that sustains patron-client networks.

Kishor’s approach to communication with the public is also unconventional. He often chastises the public rather than wooing them, holding them responsible for Bihar’s stagnation after decades of loyalty to Lalu Prasad Yadav’s RJD and Nitish Kumar’s JD(U). Unless they change now, he warns, “no one can save them.”

He also targets the 60% of voters who, he claims, want change – a departure from Bihar’s entrenched caste arithmetic and the fixed loyalties that underpin it.

The symbolism of Jan Suraaj too is distinctive: it combines Gandhi and Ambedkar, thinkers often regarded as opposites in their political philosophy. Nonetheless, they complement each other in various ways.

The test of durability

Like any start-up, Jan Suraaj offers radical alternatives but must prove its staying power. India has seen such idealistic ventures before. In the 1970s, many people across the age groups, mainly students from elite educational institutions, ventured into rural India to usher in change, disillusioned by the corrupt and immoral political system prevalent during that time.

They thought they had some form of scientific formula to transform society, but they failed miserably. On many occasions they failed to strike up a dialogue with common people and did not understand the local power dynamics or the nuances of feudal societies. They also tried to whip up the sentiment of guilt among people, like Jan Suraaj is now attempting to do.

The difference now is that Jan Suraaj appears to be a better-managed political front than the experiments of the 1970s, which were mainly driven by social movements related to issues such as land, identity and environment. Activists leading or related to these movements did not remain on the ground for long. The frustration and anxiety arising out of their inability to communicate their version of politics to people quickly creeps in, challenging their ability to stay grounded long enough to convert ideas into practice.

In an age of reels, instant opinions, and artificial intelligence, political patience is a rare virtue. If start-up politics like that of Jan Suraaj are to succeed, they must become a sustained, on-ground force. Only then can they take on the organisational might of the decades-old mainstream parties well-entrenched in Bihar’s political and social landscape.

(The writer is an assistant professor at the University of Kalyani, West Bengal)