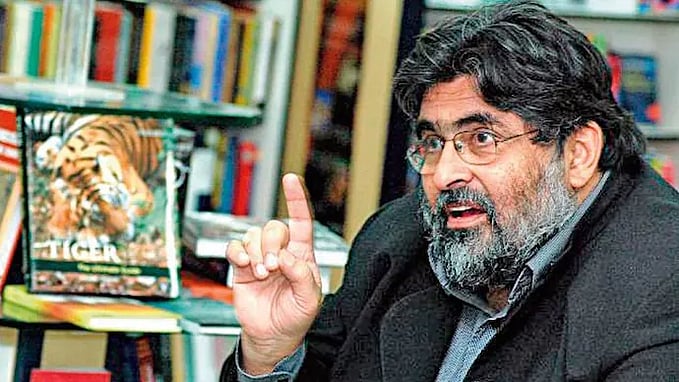

Eminent wildlife conservationist Valmik Thapar.

Credit: X/@kharge

Valmik Thapar’s passing on May 31, 2025, could not have been more untimely. In his committed and capable hands, the prospects for the tiger’s survival in India were beginning to brighten, with steady implementation of his blueprint for its protection—not just in the Ranthambhore National Park, so dear to his heart, but across the country.

Widely acknowledged as one of the world’s foremost authorities on the tiger, Thapar’s crusade to save the big cat began in his early twenties after graduating from St Stephen’s College, Delhi. Though he had no formal training in wildlife biology or conservation, he developed a deep and nuanced understanding of the tiger’s behaviour through painstaking observations in the wilds of Ranthambhore over more than five decades.

Thapar’s lifelong mission was shaped in no small measure by his mentor, Fateh Singh Rathore, an Indian Forest Service veteran, part of the first Project Tiger team and a tiger expert in his own right. A chance encounter with Rathore in Ranthambhore in 1976 radically altered the course of Thapar’s life. Under Rathore’s tutelage, Thapar immersed himself in the study of tiger behaviour, spending endless hours in the wild — observing (and often “spying” on) the big cats in their natural habitat, more as a student than a scientist. Soon, tiger conservation — and all its complex ramifications — became more than a passion for Thapar; it was a lifelong crusade.

“Once you’ve looked into the eyes of a wild tiger”, Thapar once remarked, “you’re never the same.” His own intense-looking eyes appeared to reflect a ferocity not unlike a tiger’s, as they burnt into one unrelentingly. This, together with his unruly mane and dishevelled beard, lent him a ‘wild look’ at the best of times – and more so when angered by wildlife policies that he considered unsound.

Thapar’s mission quickly became an obsession and the focal point of his life. Driven by pure passion, over the years he became the face and force behind India’s efforts to revive its tiger population. He worked tirelessly to shore up the declining numbers of the big cats through carefully thought-out and far-sighted policies primarily aimed at preserving their natural habitat and prey base, besides, of course, eliminating the bane of poaching.

In pursuit of these objectives, Thapar served on more than 150 government committees, including the National Board for Wildlife and the Tiger Task Force. The latter was set up to prescribe radical reforms after the unexplained and near-total disappearance of the big cats from Rajasthan’s Sariska National Park in 2005.

The tiger could hardly have had a more vocal or tenacious advocate. Outspoken and unsparing, Thapar had little patience for bureaucrats whose knowledge of modern wildlife management fell short. He once scathingly observed that “bureaucracy has killed more tigers than bullets ever did.” He often criticised bureaucrats for their reluctance to curb poaching through the deployment of armed patrols as well as for their refusal to open the country’s forests to scientific study. Time and again he questioned declining tiger populations, criticised inefficient systems and refused to remain silent in his constant endeavour to ensure the security of the big cat. For a globally recognised tiger expert of his eminence and expertise, his impatience with bureaucracy could perhaps be condoned.

Further, Thapar authored over 25 books and produced (as well as narrated) several wildlife documentaries for the BBC, National Geographic, Animal Planet and Discovery TV channels. In some respects, his books have shades of Joy Adamson’s 1960 classic Born Free that chronicles the life of Elsa, a lioness the author and her husband reared in Kenya from infancy to adulthood and finally released back into the wilds, having painstakingly trained it to hunt and survive on its own. As in Adamson’s epic, Thapar’s close bond with ‘Macchli’, a tigress, is highlighted in some of his books and documentaries, all of which unmistakably mirror his inherent concern for the safety and well-being of India’s tigers.

Poaching, of course, was a major stumbling block. Tiger pelts are believed to command astronomical prices in the international market even now. Further, illegal markets flourish in China and other parts of Asia, where the tiger’s much-prized organs and body parts are turned into so-called ‘aphrodisiacs’ and other bogus medical potions that the gullible easily fall for. Small wonder then that Thapar strongly advocated far stricter anti-poaching laws and insisted that certain habitats must remain inviolate – untouched and inaccessible to humans – if tigers are to survive.

Like Rathore, his mentor, Thapar had grave reservations about the practicality of peaceful human-tiger coexistence. Accordingly, he strongly endorsed relocating forest-dwelling communities out of the Ranthambhore National Park as well as other tiger sanctuaries, simultaneously ensuring that their livelihoods were not lost. However, Thapar did concede that wildlife conservation is impossible without community support and accordingly strove to integrate local displaced communities into conservation efforts.

Now that the tiger’s most passionate guardian is no more, any lowering of guard or complacency in regard to its protection could be fatal. The painful memories of what happened in Rajasthan’s Sariska National Park in 2005 (where the tiger all but disappeared inexplicably) are still fresh in the minds of nature lovers. A repeat of this in the Ranthambhore National Park – or any other tiger sanctuary in the country – would be truly tragic. Only constant and unremitting vigilance will ensure the big cat’s safety.

Thapar’s death, of course, evoked a great deal of dismay and distress not only in conservation circles globally but from people in varied walks of life as well. “This world has absolutely and sadly lost a significant voice for the voiceless,” read one tribute. Another proclaimed, “His booming voice will echo through the valleys of Ranthambhore forever.”

Will India produce another crusader of Thapar’s calibre, commitment and courage of conviction to shoulder his legacy? The tiger’s future hinges on it.

(The author is a Munnar-based freelance writer)