Though Sita remains utterly faithful to her husband, her reputation is tarnished by her abduction by a demon king.

In an Odia retelling of the Ramayana, Rishi Gautama is depicted walking along the shore with his daughter, Anjani, and his two sons. The sand is scorching, so Gautama picks up the two boys and carries them in his arms. His daughter is upset and asks, “Why must your own child walk on the hot sand while your stepchildren are carried?”

Gautama is puzzled, wondering if this is a veiled comment about his wife's rumoured infidelity. He throws the two sons into the sea, declaring that if they are truly his sons, they will return in human form; otherwise, they will return as monkeys. The two boys immediately transform into the monkeys Vali and Sugriv, and Gautama realises that his wife, Ahalya, had relations with the Vedic gods Indra and Surya while he was away.

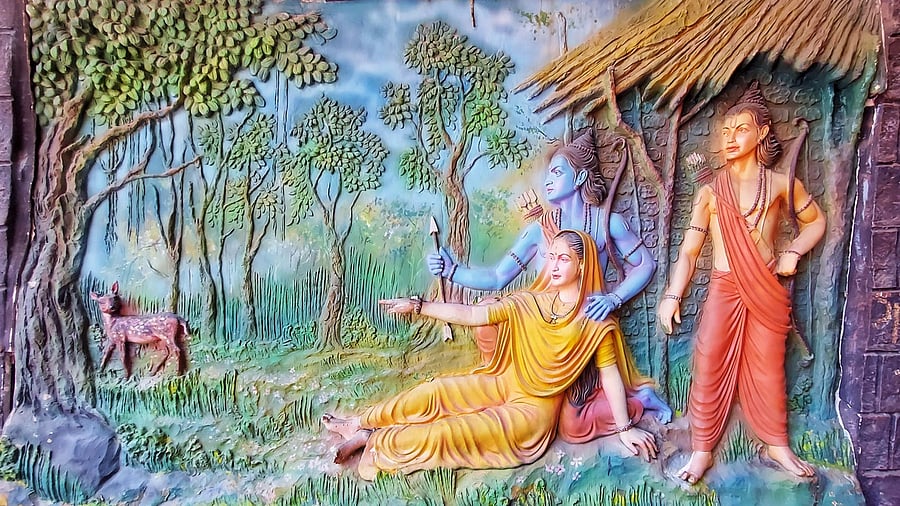

This elaboration of Ahalya's infidelity also appears in the Thai and Indonesian versions of the Ramayana. However, in more popular versions, Ahalya is cursed, becoming either invisible or turned to stone. Vishwamitra encourages Rama to restore her visibility, reanimate her, and persuade Gautama to accept her back.

One wonders why the story of infidelity is included in the Bala Kanda, the first chapter of the Valmiki Ramayana. Could it foreshadow the later treatment of Sita, who is accused of infidelity during her captivity in Ravana's Lanka? Proving infidelity was impossible without witnessing the act.

The Ramayana, in fact, presents three types of infidelity. Ahalya engages in physical relations with another man. Rishi Jamadagni's wife, Renuka, momentarily thinks of another man, representing psychological infidelity. And Sita remains utterly faithful to her husband in both body and mind, yet her reputation is tarnished by her abduction by a demon king.

Each woman faces a different punishment. Ahalya is turned to stone. Renuka's husband, Jamadagni, orders their son Parshuram to behead her, though later, Parshuram begs his father to restore her to life. Sita is abandoned by Rama to protect the royal reputation.

Parshuram's role in killing his mother — matricide — is a reason why he is forced to leave Aryavarta and seek refuge in the Dravida lands. Modern-day politicians often overlook this aspect of Parshuram's life, reimagining him as a cow protector who fights foreigners, a theme absent from any sacred text.

Parshuram is portrayed as someone who obeys his father, even to the point of beheading his mother at his father's command. Because Renuka is resurrected, she is worshipped as a goddess existing in the liminal space between life and death, fidelity and infidelity, and Brahmanical purity and non-Brahmanical impurity, between the field and the forest.

Yellamma, worshipped in northern Karnataka and southern Maharashtra, is often associated with her husband, Jamadagni. Gigantic statues of Parshuram, sporting his sacred thread — a marker of purity — are erected across India. By contrast, the beheaded-resurrected mother, the polluted-yet-purified Yellamma, receives little recognition.

The old versions of Ramayana do not speak of the practice of Sati, but in later regional retellings the concept of Sati is introduced. Ravana’s daughter-in-law Sulochana performs Sati after recovering the body of Meghnad. She is declared a Sati, or truly chaste wife. In Michael Madhusudan Dutt’s Meghanada-vadha Kavya (1861), Sulochana, the wife of Meghanada (Indrajit), is portrayed as recovering her husband’s body after his death and performing Sati. There is no condemnation of the barbaric act. Instead, in that age of Hindu Reformation, Dutt explicitly presents her as the ideal pativrata, a truly chaste and devoted wife, whose act of self-immolation is framed as heroic, tragic, and morally exalted.

In Valmiki Ramayana, Ravana’s widow Mandodari remarries the younger brother Vibhishana just as Vali’s widow Tara remarries the younger brother Sugriva. This practice of remarriage associated with ‘demons’ and ‘monkeys’ was in fact the original Vedic practice where there are hymns asking the widow to ‘grasp the hand of a living man’ and return to the land of a living. Who then stopped widows from remarrying? Who introduced strict infidelity laws in Hinduism? Was it Manu?

Devdutt Pattanaik is the author of more than 50 books on mythology. X: @devduttmyth.

(Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH)