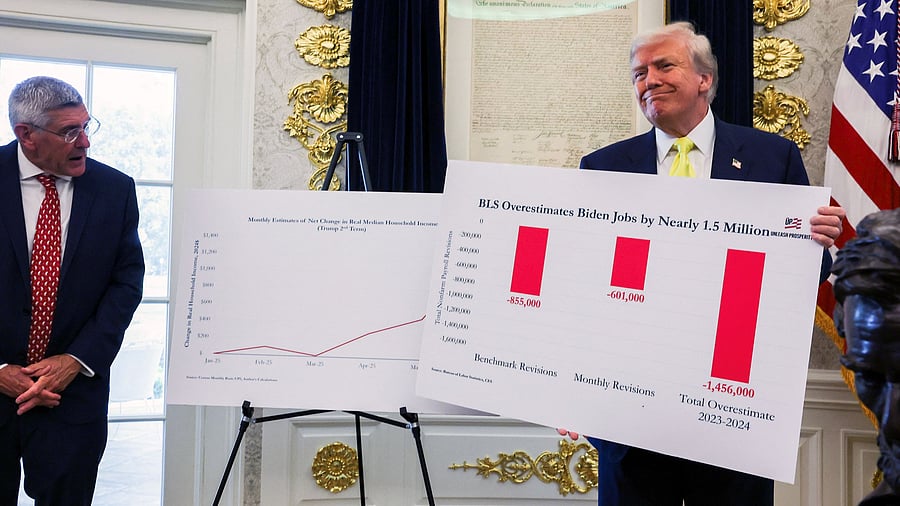

US President Donald Trump holds a board sourced from Bureau of Labour Statistics.

Credit: Reuters Photo

By John Authers

It was the revision heard ’round the world. The quality of economic data has been degrading for many years, and worsened sharply during the pandemic. It’s a global issue. But it took the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ stunning announcement last week that 258,000 fewer people had been in work in May and June than previously reported to drive the problem to the top of the agenda.

Donald Trump was furious. “Important numbers like this must be fair and accurate, they can’t be manipulated for political purposes.” He was undeniably right about this, as errors on this scale leave economic policymakers effectively flying blind. It was perfectly reasonable to fume, “No one can be that wrong?” But any suggestion of political bias destroys trust — particularly if it comes from the president of the United States.

In slightly more technical language, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent averred that cleaning up the BLS was long overdue: “The mistake that they made last week was a five-to-six standard-deviation mistake. This is like, if you got on a plane in Miami, thought you were going to New York and landed in Denver.” These complaints should themselves be revised. Bloomberg’s chief US economist, Anna Wong, estimates that this was a three standard-deviation mistake, meaning that there was only a 0.2 per cent chance of it happening in the last 30 years.

Only two days earlier, the Federal Reserve had decided in a divided vote not to cut interest rates. The BLS revisions might easily have tipped the committee toward cutting.

“Imagine that on July 3rd, we had a June NFP headline of 14,000 jobs instead of 147,000,” says Peter Tchir of Academy Securities. “Let’s further imagine that May’s reported number was 19,000” [instead of the 144,000 reported at the time]. He added that the private-sector estimate from the ADP payroll group had produced a fall of 23,000 followed by a rise of only 29,000, so imagining this was “easy if you try.”

While it took this revision to wake up the wider public, the problem isn’t new. In June, Reuters polled 100 economists and found that 89 were concerned about the quality of US economic data. Only three days before the Great Revision, a bipartisan group of economists had written to Congress urging extra investment in statistical agencies.

The problem isn’t limited to America. In May, the head of the UK’s Office of National Statistics resigned ahead of a report that found deep-seated issues with the organization’s culture. Surveying problems also dragged it into the culture wars, as it needed to retract an estimate that 0.55 per cent of the population were transgender after realizing that many respondents had misunderstood the question.

Measuring the economy has always been difficult, but nobody disagrees that statisticians aren’t doing it as well as they once did. Still, firing Erika McEntarfer as head of the BLS and claiming she’d “fixed” the numbers to damage Trump politically was manifestly unjust. The problems long predate her term, which started 18 months ago. As Eric Mould of AJ Bell points out, total revisions to employment numbers under President Joe Biden were almost identical to Trump 1.0. And Democrats complained that exaggerated inflation data compiled by the BLS hurt Biden.

But now that that the president has shot the messenger and put statistics front and center, there’s a lot to look at.

Pandemic-induced apathy

Data degradation is real and took a turn for the worse during the pandemic. The BLS itself published research showing that as its workers were forced to go online, rather than call in person, so response rates to their surveys tanked. The slide has continued, to 42 per cent from 64 per cent pre-Covid.

Job cuts exacerbated the problem, particularly after Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency swept through the agency. The BLS has closed offices in cities as big as Buffalo. Its use of imputation — taking a number from somewhere else when it has no data for a given product in a particular location — has doubled since the pandemic to more than 4 per cent.

The BLS is also increasingly imputing not from similar products in the same geography (for example, a Washington, DC number for bread inflation might be based on other baked goods in the capital), but in about a third of cases from other places altogether. It’s not plucking numbers out of thin air, as Omair Sharif of Inflation Insights LLC has explained, but it’s far from ideal.

Counting jobs and measuring price rises is made far harder by the changing nature of the economy. Two generations ago, the number on the Woolworths payroll would at a stroke give a good indication about employment in retailing. Counting those steadily employed by its modern-day successor Amazon.com is far more ambiguous.

As with political polling, the shift away from landline telephones made life harder. People are easier to reach online, where interactions are more impersonal. It’s impossible to assess the effect this has, but the experience of the University of Michigan’s industry-standard measures of consumer sentiment is instructive. In April last year, it switched to all-online. In the final month of the old methodology, the average respondent expected 3.9 per cent inflation over the next year. Twelve months later, as real-world inflation declined, this had risen to 10.9 per cent. Plainly the move online had an effect — whether people are more truthful to a human or a machine is a difficult question.

Political polarization

The Michigan survey also illustrated the damage done by political polarization. With people increasingly viewing the world through partisan spectacles, the shifts in sentiment surveys are extraordinary and extend not only to predictions for the future (where different political ideas would lead to different outcomes), but to assessments of current conditions.

Michigan started asking respondents for their party identification in 2016. The results are remarkable. Last summer, under Biden, Republicans’ assessment of current conditions scored 33.6. The lowest this number ever hit during the pandemic year of 2020, with Trump as president, was 89. Democrats gave a rating of 109 a year ago; since the election, that’s dropped as low as 59 (while Republicans are now far more positive).

It’s possible that people are skewing answers to help their “side”; but to an extent it’s driven by sincere beliefs. Sentiment data like this translates into consumer decisions, and into policymakers’ choices. People increasingly believe only the data that suit them (a trend that will be exacerbated by the president firing his head statistician).

Data proliferation

When there’s reason to doubt the official data, there are alternatives for the imaginative. In China, foreign investors use real-time measures that are harder to fudge than the official data. Total energy consumption has long been followed as a “tell” to economic activity; likewise, the prices being paid for critical commodities like iron ore and copper.

The pandemic forced new creativity from statisticians. Globally, Google mobility data could be used to work out where people were going and how much life was returning to normal. Data on transportation use, such as the US Transport Security Administration’s daily throughput at airports, or ridership of the New York subway, suddenly appeared on the Bloomberg terminal.

Increasing computer power, particularly advances in artificial intelligence, make it easy to mine documents to reveal trends, and also to set up rivals to the BLS. Complaints about its inflation methodology have spawned private competitors like Truflation or Shadow Government Statistics. This all adds to the sum of human knowledge — but creates noise.

For the future, it likely will become standard practice to use more data sources — and possibly offer a competitive advantage for investors as they try to build a better picture of the economy than their rivals. But that raises the risks of confusion — and creates more opportunities for malign actors to spread misinformation, particularly as many already inhabit echo chambers and hear only views from people with whom they’re inclined to agree.

Who cares?

Shooting the messenger provoked an outcry but has had no discernible impact on the financial markets that stand to be most affected. Investors already distrusted the data, and any new BLS chief will suffer the same problems. “For the uninitiated, this might be taken as evidence that institutional integrity — or the lack of it — simply doesn’t matter much for economic and market outcomes,” says Capital Economics’ chief economist, Neil Shearing. “That would be a grave mistake.”

Sound statistics and credible institutions to produce them remain the lifeblood of sound policymaking, he says. Markets took it in stride because there are indeed legitimate questions over the health of official US data, and because it’s doubtful that new leadership will really change the way the BLS operates or deliver the rates outcomes that Trump wants.

Further, alleging political manipulation more or less guarantees that the new candidate will be not be taken seriously. With statisticians now guilty until proven innocent, good contenders will know with high degree of statistical significance that they will be taken for a political hack.

Good economic data are a public good. Everyone — businesses, consumers, governments — benefits from them. They’re a legitimate activity for the government, and currently aren’t fit for purpose. Firing the chief statistician won’t help; a root-and-branch review of the agency, with more money and links to the private sector to produce statistics that come with confidence intervals to indicate uncertainty, just might. At least we might find our plane lands in the airport we expected.