Credit: DH illustration

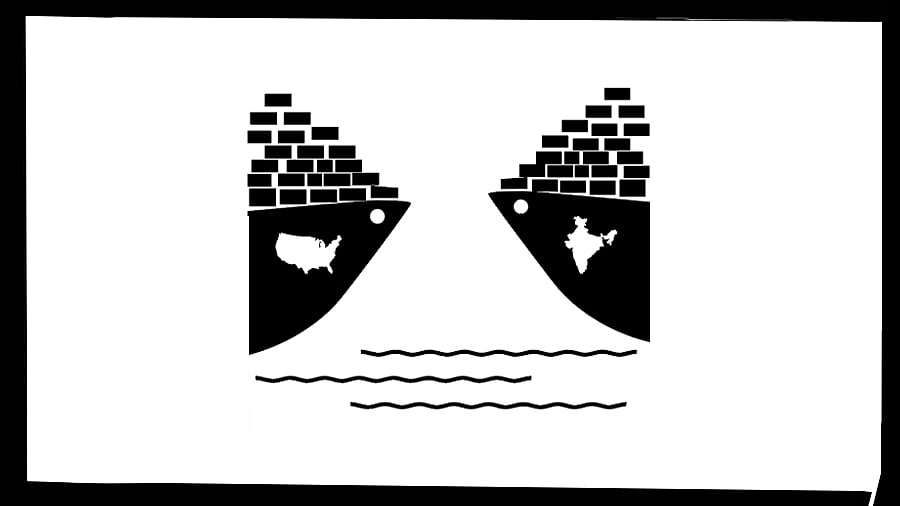

President Donald Trump has announced a 26% tariff on Indian products as part of his ‘discounted’ reciprocal tariff plan. No doubt, it is just the beginning of a story with many twists and turns to be unfolding in the coming days and months depending on the reactions of different trading partners and Trump’s counter-responses. However, even at this early stage of the game, a few tentative observations can be made about the impact on India.

First, there are a few exceptions for Indian products from the tariff like pharma, semiconductors, copper, gold, wooden products, and some critical minerals presumably because India is one of the cheapest sources of supply of these goods for the US and hence any tariffs would hurt US consumers. In fact, according to industry experts, the pharma sector (which exports 30% to the US market) would be the biggest gainer as India exports nearly $49 billion worth of pharma products to the US while importing only $0.8 billion.

Second, despite Trump labelling India as the “tariff king” on many occasions, major competitors in Asia will face higher or roughly the same tariff rate as India (26%). Our major competitors in textiles, gems and jewelry, microchips, electronic goods, as also seafood are China (34% plus already existing 20%), Vietnam (46%), Bangladesh (37%), Thailand (36%), Taiwan (32%), Indonesia (32%), Pakistan (29%), South Korea (25%), Japan (24%), and Malaysia (24%). All exporters of auto parts (the US is a major market for India) will have to pay the same tariff of 25%, presumably from May 3 while the 25% tariff would immediately apply to all assembled car exports to the US. So, India will have a differential tariff advantage (or face roughly the same tariffs) in exporting these products to the US. It is for us to use these opportunities by making the necessary reforms in our policies which often happen only under compulsion/pressure.

Third, India is in the process of negotiating a bilateral trade agreement (BTA) with the US. As part of the ongoing ‘deal’, India will have to reduce tariffs on some products to get further tariff concessions from the US. Here, we can reduce tariffs on EVs (especially Trump’s friend Elon Musk’s Tesla) which, even with zero tariffs, would be significantly more expensive than Indian EVs. Tariffs can also be reduced for agricultural products like some fruits (avocados, apples), nuts, raisins, and specialty cheese which are either not produced in India or significantly higher priced than Indian competing products. So long as tariffs on rice, wheat, sugar, and cotton (involving a huge number of farmers) or milk and common varieties cheese (where many small rural producers are involved) are not reduced, the adverse impact of tariff reductions would be limited to the affluent and should be politically manageable. We can also import more oil and gas from the US at the expense of imports from Russia, Middle-East or Latin American countries, without causing any significant rise in the prices of these fuels. In other words, there are sectors where we can reduce tariffs as part of the deal for having lower duties on exports of some other Indian products. So, even if some jobs are lost in a few import-competing sectors, there will be job gains in some export sectors.

Making sense of the math

Fourth, reducing tariffs on inputs like components for electronic goods (like mobile phones), specialty steel, and other mineral products would reduce the cost of production of Indian goods which, by improving the international cost competitiveness of Indian products, would help reduce imports and/or increase exports. So, a carefully chosen package of tariff reductions, as part of the BTA, would not necessarily hurt Indian interests.

Fifth, the Trumpian method of calculating the tariff rate a country is charging on US goods is bizarre. Trump claims that it measures the impact of tariffs plus non-tariff barriers plus currency manipulation which is very difficult to reduce to a precise single number. In practice, he divides the trade deficit number of the US vis-à-vis a country by the exports of that country to the US. For example, Indonesia has a trade deficit with the US of $17.9 billion. Its exports to the US are $28 billion. 17.9/ 28 = 64% which Trump takes as the Indonesian tariff rate on US goods. The earlier imposed tariff on Canada and Mexico was presumably to punish them for not sufficiently restricting smuggled fentanyl export to the US. Thus, the so-called reciprocal tariffs are arbitrary numbers and the entire exercise reduces to bargaining or deal-making.

Sixth, should India negotiate or retaliate? Given that the WTO has become a toothless body, there is no point in escalating a tariff war with the US or taking any trade dispute to non-functional WTO courts. In this bilateral power game, the better option is to try to negotiate a deal, unless and until the rest of the world comes to a point where they are forced to form a united bloc against the US.

Finally, when would this madness by Trump stop? It would stop only if his policies tumble stock markets, reduce the wealth of his billionaire friends, and/or raise prices in the US to enrage his working-class supporters who voted him to power hoping that he would bring down prices and bring home manufacturing jobs. High tariffs would surely raise prices in the US immediately. Even if tariffs induce some investors to move factories to the US, it would take years to set up and operate new manufacturing plants, and that, too, will happen only when the investors become certain that these higher tariffs will remain even after Trump’s term ends.

(The writer is a former professor of Economics, IIM Calcutta, and Cornell University, US)