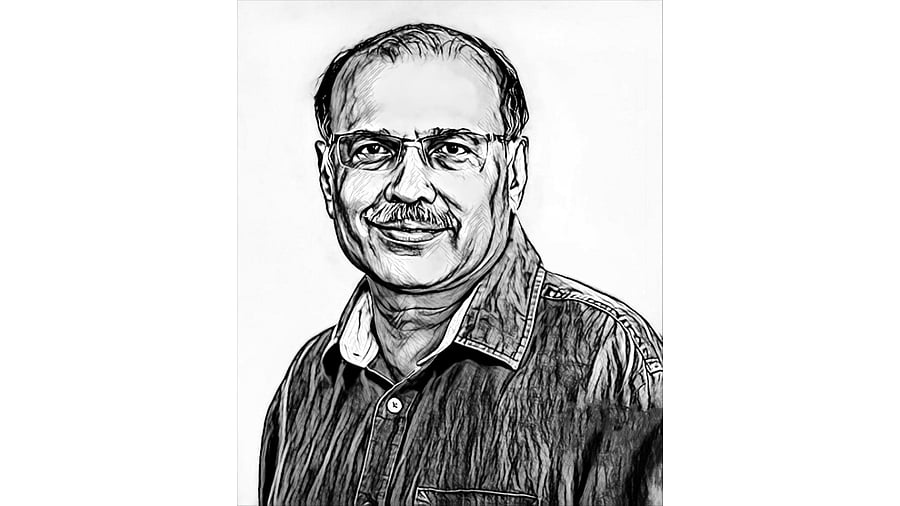

Capt G R Gopinath (Retd.) builds bridges, sometimes by tearing down walls. He is a soldier, farmer, and entrepreneur.

Credit: DH Illustration

Bengaluru has been witnessing a flurry of congregations involving varied Hindu denominations and sub-sects such as Vokkaligas, Lingayats, Kurubas, Valmikis, scores of Brahmin communities under one umbrella, and various sub-groups of Sri Vaishnavas, the followers of Ramanujacharya. These gatherings were, typically, exercises aimed at infusing a certain pride in caste identity while some also came with political overtones and demands for greater representation in the government. All were attended by the respective sects’ supreme heads; all had an unmistakable streak of jingoism. Seers from other castes were also in attendance but that is how optics play out.

I received invitations to address two gatherings in quick succession – one from the Sri Vaishnava Sabha and the other from the Brahmana Mahasabha – to deliver inspirational talks on entrepreneurial spirit, apparently found lacking in the community. The three-day celebrations were grand, complete with homas, vedic chants, and shlokas. After initial hesitation, I accepted the invitation as I reflected that we all have multiple identities. I’m a Srivaishnavite, a Brahmin who passed out from reputed military academies, a soldier attached to a particular regiment, a farmer and an aviation entrepreneur. I run a company, I’m a member of my village temple committee, I’m a Kannadiga, an Indian, and a citizen of the world – what Kuvempu called Manuja Matha, the universal man. Adikavi Pampa, a Jain from Karnataka, said 1,000 years ago: Manushya jati tanonde valam. There is only one caste: the human race.

My distinct identities can coexist in these disparate groups and my persona is thereby enriched in myriad ways. Like a land and its people, its languages, art, architecture, music, culture, cuisine, religious outlook and ideas can also benefit when there is commingling of people across faiths and ideologies.

Before I was ushered to the stage, a group of highly accomplished people engaged me in a conversation. One of them bemoaned the declining Brahmin population and said something needed to be done. I was stunned. Since I knew him well, I said, half in jest – “Sir, you forget you married a Lingayat, your son has wedded a Christian, and daughter a non-Brahmin. My daughter has married a foreign national. How will Brahmin population increase? Be happy.” I also quoted Nrupathunga’s words from Kaviraja Marga, the first literary work in Kannada language – Kasavaravembudu, nere serisalarpade para vicharamum para dharmamum (True wealth is gained through assimilation of diverse ideas, philosophies, and faiths).

As I walked up to the podium, I wondered how to convey my tumultuous thoughts to my hosts and the audience without offending them. After the exhortations to the young which was the easy part – dream the impossible, blaze your own trail – I narrated a story on Ramanujacharya by Jnanpith awardee Masti Venkatesha Iyengar. When Ramanuja escaped to Karnataka under the threat of the Chola kings of the time, he settled initially at Saligrama, a small village near Mysore, before establishing his ashram in nearby Melkote. His reputation as a seer with a luminous mind and a social reformer preceded him. His discourses attracted thousands; he converted many non-Brahmins including Dalits into the Shri Vaishnava fold. A temple priest and his wife, Shyamalamba, took care of him.

Once, when Ramanuja fell ill, the priest and his wife took turns to nurse him and massaged his aching body. The next night, delirious from the raging fever, he felt the sensuous, unfamiliar touch of a woman’s hand. Ramanuja was aroused out of his sleep. A couple of days later, he recovered and learned from Shyamalamba that the woman was his wife he abandoned many years ago. She had come searching for him and was around for two days – “That night, overcome by memories of her happier times with you, she couldn’t resist her longing and she pressed your legs.” The acharya was speechless.

Masti asks: “For the guru, his knowledge may have been a higher pursuit, his philosophical insights on the nature of the universe and its creator may be nobler, but was he not inconsiderate in deserting his naive, young wife over some minor discord, without a thought for her future?”

Masti was a devout Shrivaishnava. He performed pujas, recited shlokas, chanted sandhya vandana, and sported a nama on his forehead. But he had the courage to question the conduct of his guru. His empathy and humanism transcended his orthodoxy. Ramanuja himself, while young, questioned and disagreed with his guru Yadava Prakasha’s Advaitha philosophical bent of mind. He parted with the guru to found the Vishishtadvaita school. I concluded by recalling physicist and Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman: “I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.”