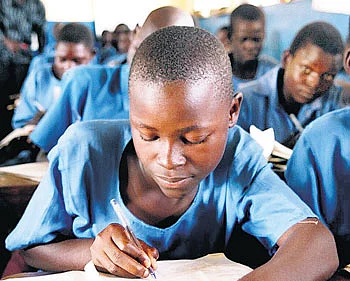

To have all children in school by ’15 is one of the UN’s goals that will come closest to achievement.

Since the turn of the millennium, the world has made stunning progress toward the goal of universal primary education. In sub-Saharan Africa, enrollment in primary school has risen by 18 percentage points; in Asia and Latin America there has been more limited progress. While globally, 69 million school-age children do not attend school now, in 1999 that figure was 106 million. This is a huge achievement.

The aim of having all children in school by 2015 is one of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals that will come closest to achievement. Countries have made progress by abolishing school fees, building schools in remote areas, switching the language of instruction to the one the children actually speak and giving families incentive to send children to school with school food. In some countries, parents who keep their girls in school get sacks of food from the World Food Program. One Ethiopian programme that encourages girls to stay in school gives each girl who does so a sheep or goat.

But the influx of new students in many places has overwhelmed school systems that were already barely functioning. Poor countries devote their education budgets disproportionately to universities, because urban, middle-class students and their families have political clout. Neglect of primary schools in rural areas and urban slums is epic.

Schools in poor parts of Latin America, Asia and Africa often have no books or teaching materials other than a chalkboard. The method of instruction is rote repetition. Teachers sometimes don’t speak the same language as their students. Absenteeism — among teachers, not just students — is astronomical, and some teachers just never show up at all.

Now add to that class sizes swollen to absurd levels, as governments have not been able to add teachers and new buildings at the same rate as they are adding new pupils. There are schools in Malawi with 175 children per class. And the children coming to school for the first time now are the least likely to make progress, because they are starting late and are disadvantaged by the same factors that kept them out of school before — they are from the very poorest households, their labour is needed, their families neglect girls.

So are the tens of millions more children who have entered school in the last dozen years learning anything?

The development organisation Save the Children carried out some surveys to find out. The answers were dismal. “We were looking at the number of children reaching the upper grade of primary school without being able to read and do basic math,” said Amy Jo Dowd, Save the Children’s senior adviser for education research. What was most shocking to the organisation was that these children included those in schools that Save the Children was supporting. The group was building schools and playgrounds, training teachers, providing materials, encouraging PTA’s — and even in these places, children weren’t learning. In Tigray, Ethiopia, 23 per cent of third graders in a school supported by Save the Children could not read a single word in one minute. In Nepal, the number was 50 per cent .

Literacy Boost

Save the Children’s response was to create Literacy Boost, a programme that is now in schools in 12 countries and is expanding to another six this year. Literacy Boost isn’t a curriculum. It works with the existing national curriculum, in any language and culture. It holds monthly workshops with teachers to train them in effective teaching methods, works with villagers to create out-of-the-classroom support for reading in families and communities, and carries out rigorous assessments.

Idalina Mauaie is a teacher in the village of Chingoe, Mozambique. She started Literacy Boost with her first-grade class, and has continued those methods each year with the same students, who are now entering fourth grade. Before the programme, she was one of the lucky teachers — she had only 32 students, she said, and each one had a textbook. But she said that her instructional methods have changed greatly. “Before, I just used the textbook,” she said. “Now I use teaching materials that I make to facilitate learning. I use group work — I can be evaluating students in one group while the other students are doing their work.” She made wall posters with basic points — for example, how syllables are divided. “It helps students remember — they can leave with the lessons.” She says that all of her students can now read and write.

The four-hour workshops, held one Saturday a month for nine months, emphasise five core skills for reading mastery — knowledge of letters, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, reading fluency and comprehension. Each training section focuses on how to teach and assess one skill. The teachers learn interactive methods, such as songs and games. At the end of each session, teachers in the same grade meet, talk about what is and isn’t working, and plan the next month’s lessons.

The most innovative part of the programme is the work outside the classroom. The goal is to expose children to reading as much as possible. This often starts with simply maximising children’s exposure to print — in some places, the only writing a child sees is what the teacher puts on the blackboard.

Each school creates a Book Bank, a mini library of 200 to 250 books the children take home with them. This seemed outrageously ambitious to me — I once toured a school in Peru where the teacher showing me around warned me “our library is not very complete.” I wondered how villages in Africa could come up with books when there are very few published children’s books, especially in indigenous languages and there is no money to buy books if they did exist.

In a few places, Save the Children has worked with local publishers or nongovernmental groups, or even government ministries, to print books. But more commonly, the programme depends on an ingenious solution -- the books are homemade. Sometimes adults write down favourite stories, but often the authors are children.

Children take the books home and read with parents or older children. Community volunteers lead reading camps — in Chingoe, two school parents hold these regular workshops, playing letter and word games with children, often using homemade vocabulary cards. The village also had a reading fair, with reading contests, storytelling and exhibitions of student drawings with text. It was particularly important to reach households where parents can’t read, said Dowd.

The third component of the programme is assessment: children are tested when the programme starts, and then their skills are re-tested periodically, to see where each child needs more attention. Save the Children also recruits schools that are not in the programme to serve as a control group. Four countries have completed at least one year of Literacy Boost: Mozambique, Malawi, Nepal and Pakistan. All show significantly larger reading gains by students in the programme than in the control groups.

Students in Literacy Boost classroom attended school more often than students in the control group. Even more encouraging, the gains were biggest among students who were furthest behind. Literacy Boost can even help compensate for huge class size: in Malawi, the programme works just as well in the 175-student classroom as the “small” 75-student classroom. In schools outside the programme, by contrast, achievement drops as class size rises.

The problem that Literacy Boost cannot attack is the case of the missing teacher. For many reasons — low salaries, the undesirability of living in remote villages, poor morale, high rates of HIV — teachers are often AWOL; World Bank studies found absenteeism to be about 20 per cent in Uganda and the same in rural primary schools in western Kenya.

Literacy Boost is counting on a mobilised community to lean on the teacher. Community monitoring, however, has shown to have little effect on teacher absenteeism. There are things that apparently do work: Esther Duflo, the Harvard poverty researcher, reports on an experiment in 60 rural schools in India: each teacher received a camera with a tamper-proof time and date stamp. Each day, a student had to take a picture of the teacher with students at the beginning and end of the day. Teachers were paid according to the number of days they actually were there. It was a complete success.