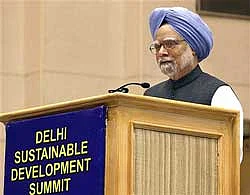

“A modest accord that is fully implemented may be better than an ambitious one that falls seriously short of its targets. This is the lesson that was learnt with regard to the Kyoto Protocol,” Singh said here inaugurating the Delhi Sustainable Development Summit, organised by The Energy and Resources Institute.

Environmentalists for long were suspecting some countries of joining hands to come up with a new treaty junking the Kyoto Protocol. Some of the Kyoto provisions, however, could be copied and pasted onto the new agreement depending how the negotiations progress.

Mentioning the centrality of the UN negotiation process, Singh said there was much in the Copenhagen Accord that could bring consensus on the two-track negotiating process.

For this to happen, this process has to recommence in right earnest, perhaps from March this year, Singh said.

But on Thursday, the UNFCCC executive director Yvo De Boer said the closest date to resume the negotiation could take be around Easter (April) and certainly not in March.

Boer admitted that though many countries were “struggling on how to deal with the Copenhagen accord” it is essentially a document with a “huge political significance.” “The most important factor would be not to overplay the Copenhagen accord. Its a key political document. People should have it in their back pocket and keep it there,” Boer said.

Singh, on the other hand, said the purpose of the Copenhagen Accord was to contribute to the negotiations on the Kyoto Protocol and on Long Term Cooperation that began in Bali to bring the US onboard as it is not a party to the Kyoto Protocol. “It (the accord) is not a substitute but a complement to these core international agreements,” he said, adding that India would negotiate in a “spirit of flexibility.”

The prime minister, however, did mention the UNFCCC principle of “common but differentiated responsibility,” which puts the onus on rich countries to make greater financial contribution in cleaning up the earth but allow the developing world to address their poverty alleviation needs first. “The lack of global consensus on burden-sharing is an even greater barrier to securing an agreement,” Singh said.

Industrialised countries need to recognise more clearly their historical role in the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and they should respond with bolder initiatives to contain their future emissions, he added.