We were in A Prasad’s office in Bengaluru, on Palace Road, staring at a window. It was 4.40 pm on March 29. It was drizzling. Leaves started to bob. The light was soft. The birds were loud. I drew in the heady scent of the earth.

“Did you predict the rains for today?” I asked Prasad, in charge of the weather section at the Meteorological Centre in Bengaluru, which forecasts for the state of Karnataka. “Yes. I made that forecast in the morning, and a while back, my team issued a nowcast. I am happy we got it right.”

I was in the room where the nowcast (a three-hour forecast) was issued. Met Bengaluru has a lot more women than men, including Geeta Agnihotri, head of the Karnataka chapter of Indian Meteorological Department (IMD). I was just telling this to an officer when she cut me off and returned to her computer screen.

A temperature map of India needed attention. Pink-red patches had appeared over south Karnataka.

Between sips of tea, another officer was following the development on a grid of LED screens on the wall. Thunderstorm accompanied by lightning with light to moderate rains likely — they emailed an alert to district commissioners of chikka, rama, mandya, chika, ram chika, bengalur, mysurur, kBengaluru, Tumakuru, Chamarajanagar, Mandya, Kodagu, and Ramanagara districts in minutes. Chikkapbalkappura, ramangara, mandya, benagluru rural, ramnagar, chamrajanhgara, kodagu,

The weather is a continuously changing phenomenon and a forecast is but an educated guess. Still, it is dismaying when forecasts fail. That happened to Prasad last May, one month after he had shifted from perennially hot Chennai to unpredictable Bengaluru. “I hadn’t predicted thunderstorms for Bengaluru. It started raining heavily past midnight. I was on call with duty officers from 1.30 am to 6 am,” he recalled.

IMD is often criticised for getting monsoon predictions wrong. Forecasting for mid-latitude regions, say western Europe, is relatively more accurate than for tropics like India as weather systems move slowly in the former, Suryachandra A Rao, scientist at Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune, explains.

Who needs it?

Short-term or long-term, weather updates are crucial for farmers, livestock owners, sailors, coastal communities, sports organisers, and for those in sectors like aviation, power and transport. The stakes are high. That aside, how many people keep an eye on the sky?

Two officers smiled at my question. One said: “In the summer, housewives call to ask if it will rain today as they want to dry happala (papads) in the open. Samosa and bajji sellers ask if it is going to rain. Bakeries make fewer cakes when it rains.” Another piped in: “We get calls from those planning VVIP visits, or just driving to Mysuru. An old man would call every hour, till 4 am, to enquire about humidity and pressure. He had asthma.”

Daily routine

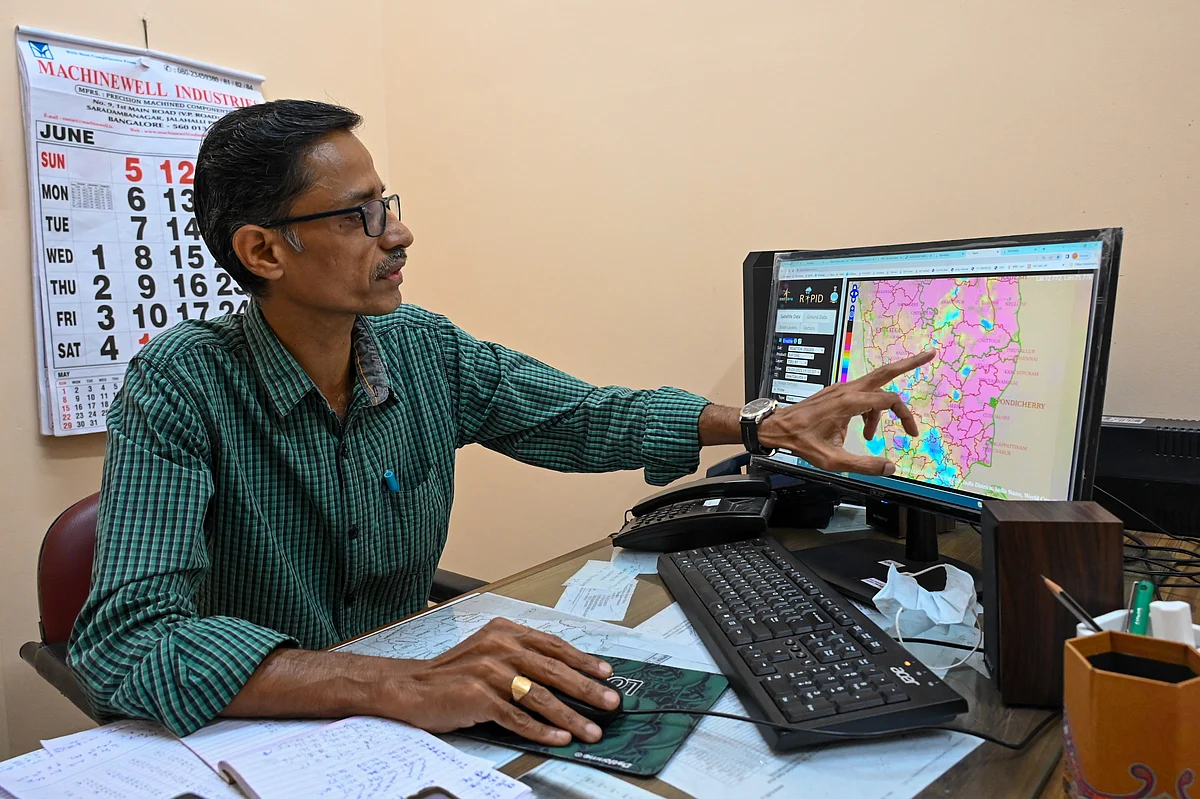

This was my second visit to the met office in three days. On Day 1, Prasad strode into his office, thin, bespectacled and with a mask on. It was 9.55 am. He made quick phone calls. He opened multiple windows on his computer and went back and forth on a comparative table of weather models, satellite images and radar maps.

Taking a notepad, he scribbled March 27 on top and filled Ds and Is across three columns and five rows. “Karnataka is divided into three sub-divisions (South Interior, North Interior, and Coastal) and 31 districts. If it is likely to rain over 1-25% of a subdivision, we mark it isolated (I). Over 25-50% area, we call it scattered. Between 51 and 75% is fairly widespread. Beyond that, it is widespread. If nothing, it is dry (D),” Prasad explained. Glancing at his wristwatch, he said, “Let’s go.” It was 10. 30 am. Between our interview and admin work, he had made his sub-divisional forecast proposal for Karnataka.

Every day, at an online meeting, scientists from the Regional Meteorological Centres (RMCs) and met centres table their forecast for five days. The proposals are approved or tweaked mutually and a national forecast is drafted by 1 pm. That day, Karnataka’s forecast got an easy nod while some deliberation happened over Kerala’s. The Bengaluru, Thiruvananthapuram, Hyderabad and Amravati centres come under the Chennai RMC.

He returned to office, now to do district-level, Bengaluru-specific, and severe weather forecasts for the day. “Please excuse me?” the mild-mannered Prasad said.

Frog in a jar

I hung around in the lobby. Weather observations were pinned on the notice board. Telecommand and its Hindi word ‘Duraadesh’ were scrawled on a whiteboard. IIMD was established in 1875, and it now runs an app called Meghdoot to provide crop advisory, I gathered from the posters.

Admiral Robert FitzRoy pioneered daily weather predictions and came up with the term ‘forecast’, I scrolled down a BBC article. A sailor saddened by the loss of life at sea in Victorian Britain, he started issuing forecasts over the electric telegraph. “Prophecies and predictions they are not; they are a result of scientific combination and calculation,” he wrote while forwarding his two-day forecast to newspapers. He was an affront to the practice of detecting storms by looking at a frog in a jar or a bull at farms. The Times because the first daily to print a forecast in 1861.

Today, maps, computer weather models, and satellite images are giving predictions about rain and wind changes. So what are meteorologists doing manually? Has technology changed their role?

Humans of met

As I paced up and down, I saw more systems than staff. “We work in shifts. Even women do night shifts. A met centre runs 24 hours,” said a climatology officer, standing in for a colleague in the state daily weather section. Almost all employees have a background in physics, maths, and statistics, and 20 years of experience on an average.

At 2.15 pm, an officer marched out of the building. A while back, she was taking down wind speed and direction from an elaborate setup on the terrace. The sunshine recorder became my favourite. ‘Burn a piece of paper with a magnifying glass’ - it reminded me of the experiment we did in school. It comprises a glass ball that focuses sunlight onto a blue card to char it.

The sun was beating down on the leafy campus. The traffic was bad, and horns were blaring. If not for the assignment, I wouldn’t have followed her outside. She stopped at the observatory – a no-trespassers zone.

She opened a rain gauge, pulled out a beaker and quipped, “No rain”. Moving right, she lifted a white shutter open, then another. “These are Stevenson screens”, used to cover metrological instruments, she said. She jotted dry bulb, wet bulb, maximum, and minimum temperatures, and inky readings from hygrograph and thermograph. I didn’t need proof but there it was, 34.2°C!

Squinting her eyes and shielding with a hand, she looked up. “Cirrus is more,” she remarked at the wispy clouds soaring high. “Stratus,” she pointed to a lone cloud, hanging low and flat.

An Automatic Weather Station (AWS) stood right there. It generates data every 15 minutes while a manual one data every three hours. Then what use are the manual readings? Muralidhara B S, S, an officer from the maintenance section, explained later: “AWS is electronic equipment. It works on power supply and with sensors. If it is not calibrated properly, the reading won’t be right. AWS is preferred in remote, inaccessible locations.” Karnataka has 23 manual observatories, 36 AWS and 39 Automatic Rain Gauges (ARG), he told me. Bengaluru city has the most – seven.

“Come rain or storm, we have to record these observations every three hours every day, starting at 8.30 am. Met centres around the world take these readings at the same time,” she said and went upstairs to dispatch the data to Chennai, which travels to the World Meteorological Organisation.

For upper air observations, they release weather balloons, once at 5 am and again at 4.30 pm. “These can drift 21 km away. Earlier, people would bring burst balloons to the met office and get a token amount in return,” she said when we met to release the evening balloon. It vanished in seconds.

Back in the weather section, an officer had her eyes were fixed on a colour-coded map of India. “We can at least take our eyes off the screen here, but not in an airport observatory. There, we have to alert the authorities about fog build-up and low visibility immediately,” she said. Bengaluru has two of them – at Kempegowda International Airport, and HAL Airport.

When I took the machine versus human debate to S Balachandran, head of RMC Chennai over a call, he said automation isn’t a bad thing. IMD is now able to issue five-day forecasts instead of two-day ones because of technology. But he was of the view that new tech, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), can throw humans out only if it is consistently better and proven so.

Police curiosity

Record-keeping is another key mandate of the weather department. “Do you remember the (2020) DJ Halli riots case? The Bengaluru police asked us if it had rained that day. They feared rain could have washed away the bloodstains,” an officer at the climatology section illustrated the kind of queries they field.

Another officer pitched in: “Six months ago, a boy and a girl fell from the Electronics City flyover and died. Police wanted to know the wind speed at the time of the incident.” Insurance companies call frequently to ascertain if a roof, compound wall, car or windmill blade fell prey to nature’s fury. “We still get calls related to last year’s Bengaluru floods,” she added.

Civil contractors source rain data to check if an area is suitable for building bridges and laying metro tracks. Transport operators seek temperature and moisture records before they deliver a big haul of medicines.

Weather data is free for college students. In other cases, a 24-hour weather report for an insurance claim can cost you Rs 3,150 plus taxes. The more granular and historical your ask, the more you shell out. “In November, a party paid Rs 3.5 lakh for rain data of the past 30 years,” an officer sais. Weather nerds like Praveen Chandrasekaran from Bengaluru despise IMD’s pay-for-weather data service.

Information by Agro Advisory Services is free too. Two decades ago, the section would publish a one-prediction-fits-all advisory for farmers across Karnataka. Today, every Tuesday and Friday, it sends out bulletins for 10 agro-climatic zones, covering poultry, livestock, fishery, horticulture and seed transport. “Weather vagaries are increasing due to climate change. Crop production and food security are at risk,” said director M Rajavel, explaining the need for real-time and impact-based predictions.

I was then ushered into the Records Scrutiny Section. Data coming from all observatories are reviewed, neatly bound in blue covers month after month, and archived in tall columns here. Digital copies are forwarded to the national data bank IMD Pune for climate research. ‘Bangalore,’ a pocket-sized observation book from 1895, is the oldest record here. “Nice handwriting,” I remarked as she flipped it. ‘Hassan, 1928’, and ‘Chitradurga, 1905’, were other old documents.

Hobbyists v experts

Weather forecasting is no longer an exclusive bastion of the met centres. Weather bloggers are on the rise and each city has its network. Students, businessmen, engineers, biologists, and bankers glean data from personal AWS and publicly-available charts and maps, and make hyperlocal predictions.

Pradeep John from Chennai, Rajesh Kapadia and Ankur Puranik from Mumbai, and BNGWeather of Bengaluru have logged a following for their forecasts. And Sai Praneeth from Andhra Pradesh was hailed by prime minister Narendra Modi for providing weather updates to farmers.

The Bengaluru bunch I interviewed in the past claimed IMD’s local forecast was not always reliable, which is why they had turned to study the weather in their neighbourhoods. IMD stations lack maintenance was another complaint.

Muralidhara said repairs are done timely but remote stations are challenging to monitor. Solar panels, data loggers and batteries are often stolen from unmanned equipment. Honeybees, insects, rats, and lizards are a bigger nuisance. “They make beehives or cut the wires,” he said, bursting into laughter. Then, the tuskers. “Not only is the connectivity to Hanur and Gundlupete in Chamarajanagara limited, but we also have to return by 4 pm before the elephant movement starts.” The Agumbe automatic station in Shivamogga district is the most challenging. “It’s rainy, foggy, cloudy for most of the year there. Solar panels don’t charge enough,” he explained.

That we need more observatories to deliver micro-weather predictions got a unanimous vote. However, it is difficult to find obstruction-free locations to set up weather stations in mega-cities like Bengaluru, Muralidhar said.

Prasad said the same when I asked why Karnataka doesn’t have its own radar, a long-pending demand. It currently relies on radars in Goa, Kochi, Hyderabad and Chennai to study precipitation and storms. “We will have it shortly. Site selection is on. Bengaluru will get first, then Mangaluru,” he informed.

I had one last question for Prasad. Is April going to be kinder? March has been blazingly hot. 39.2°C is the highest April temperature Bengaluru has seen. That was in 2016.14.4°C was the lowest, in 1894. 34.1°C is the average April temperature for 30 years... Prasad pulled out the numbers. Except for one day or two, he said. “But will it rain?” I persisted. “Yes, yes. Likely on April 19, 20 or 21,” Prasad said, laughing.