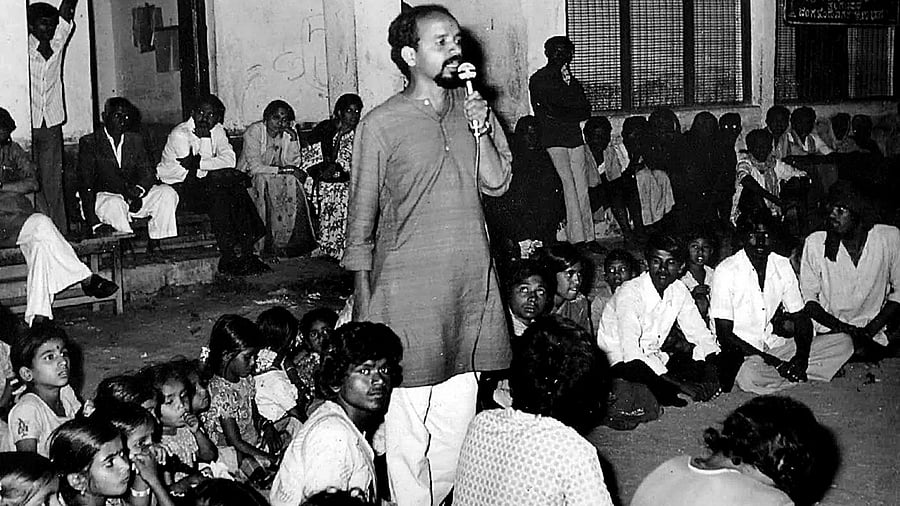

The story of theatre group Samudaya is incomplete without delving into the years leading up to its birth. The group introduced street plays to diverse communities, using drama to deliver social messages. Every story of Samudaya’s origins starts in the 1970s — a decade charged with revolutionary energy.

In Karnataka, the ’70s were marked by then-chief minister Devaraj Urs’ successful implementation of the Land Reforms Act, his minister B Basavalingappa losing power for criticising upper-caste domination in literature (he called the writing ‘boosa’, or cattle feed), and the birth of the Dalit Sangharsha Samiti (DSS). It was also in this decade that prime minister Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency. Samudaya was born in this context — as a direct reaction to the changing political climate.

“In Samudaya, all of us had a commitment to society,” says Purushottama Bilimale, chairman of the Kannada Development Authority. “We showed our social commitment by reacting seriously to contemporary events.”

Founded on German dramatist Bertolt Brecht’s conception of theatre as a tool for rational thinking rather than emotional catharsis, Samudaya took theatre from closed auditoriums to the streets.

Sanath Kumar Belagali, a journalist and previous associate of Samudaya, recalls: “The group is special because it created its own audience. From factory workers, daily wage labourers, to students, everyone started coming to watch Samudaya’s plays.” This cross-sectional appeal was not only represented in its audience but also in its ideology. There were Marxists, Lohiaites and Ambedkarites in its ranks.

Samudaya used theatre as a medium to comment on current affairs, addressing caste-based violence, superstition and women’s issues. The group energised a whole populace from Bidar to Chamarajanagar. Though based in Bengaluru, the organisation’s reach was spread across Karnataka. Vartha Patra, a monthly magazine published by Samudaya, also played a significant role in building this reach.

“At a time when there were no avenues to publish our writing, magazines like Panchama and Samudaya Vartha Patra gave us opportunities,” says Bilimale. “For someone like me, sitting in Sullia, to be published in a Bengaluru magazine was an unimaginable surge of confidence.”

This decentralised approach was also visible in the cultural jaathas (processions), which Samudaya pioneered. Jaathas were first held in small villages and towns, offering artistes the opportunity to express their views and deliver a social message through music, drama, and visual art. Performances that stood out would converge in Bengaluru.

Post-’90s challenges

The nineties and the noughties were marked by the rise of Hindu nationalism, following the liberalisation of the nation’s economy, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid. In 2001, the now-President of Samudaya, C K Gundanna, was attacked during a street performance that advocated communal harmony.

Such problems existed before liberalisation as well. In the ‘80s, a seer and his followers from Kuduremothi, Koppal, sexually assaulted two women and paraded them naked. Samudaya sought to create awareness by performing street plays across the state. Bilimale remembers playing the part of the seer and being attacked by RSS supporters. “We were smeared with cow dung and chased away from Nehru Grounds in Mangaluru,” he says.

But, he adds, “The kind of problems we faced in the ‘70s and ’80s were very different from what we face today.”

Despite the insistence of many people like Bilimale, it is hard to ignore the similarities between then and now. Tyrants and so-called holy men still exploit people, and have also adapted tools of the technological era. What seems to be different today is the way progressive cultural organisations like Samudaya are reacting — or not. Responding to contemporary developments through satire and mockery used to be its approach.

In the last week of August 2025, Samudaya began its year-long celebrations, where three plays, ‘Jugari Cross’, ‘Buddha Prabuddha’ and ‘Janatha Raja Shivaji’, were staged. The newest among these three is a decade old.

This refusal to engage with new material plagues the Kannada amateur theatre scene, and is not restricted to Samudaya. But it becomes more evident when your identity is strongly connected to your history as a socially committed cultural movement that prided itself on reacting strongly and immediately to its time.

“Samudaya has a legacy and it has done great work in the past,” says theatre person Lakshman K P. “But I think it is time to rethink their way of theatre, art, and movement — because the times have changed.”

Bilimale agrees. “We have become outdated now.”

Non-existent protest

Protest culture in itself has significantly changed in the state. While the Hindutva government at the centre arrests protesters and keeps them in jail without trial for half a decade, the state government has relegated protests to Freedom Park. In 2019, Gundanna had expressed his disillusionment over the people’s attitude towards protest and the culture of dissent.

With the advent of social media and the media’s abdication of its responsibility towards social commitment, it might appear silly to look at an amateur theatre group for the same. But, given its history, celebrating the past and basking in its glory only seems disingenuous. Introspection about possibilities in a changing world is also a necessity.

In Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus, the angel’s eyes seem to be looking at the past, while the “storm of progress” (Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History) blows through. That’s what the state of public discourse looks like today: fixated on nostalgia while the future is left uncertain. Much like Samudaya.