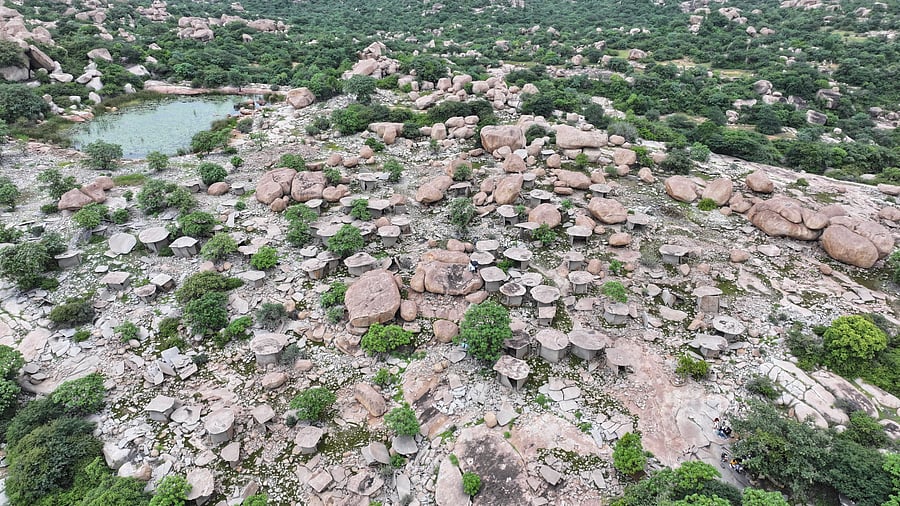

An aerial view of the central cluster of dolmens at Hire Benakal near Gangavati, with the rock pool at top left.

Credit: Photo by Kailash Rao

After centuries of obscurity, the extensive megalithic site near the village of Hire Benakal in North Karnataka has suddenly shot into the limelight, with the possibility of making it to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. And rightly so, for apart from being one of the most spectacular megalithic sites of the world, the larger area around Hire Benakal — with its rich ensemble of vestiges from prehistory — offers us the best opportunity to understand megalithic culture and belief systems. These vestiges, ranging from a profusion of rock art panels, to ringing rocks, evidence for prehistoric habitation and the monuments themselves, give us a peek into the minds of their creators.

Hire Benakal is virtually a museum of megalithic forms, the site even providing clues into the methods employed by the megalith-builders for the extraction and dressing of stone, and subsequent erection of the various megalith types. Most eye-catching are the tall dolmens — box-like structures made of four vertical slabs surmounted by a heavy capstone, often with a circular porthole in one of the vertical slabs.

However, there are over a thousand megaliths of various types: dolmenoid cists, which look like smaller dolmens sunk partially into the ground; irregular polygonal chambers, which can be thought of as crude dolmens, and many other forms.

A large stone drum, presiding over the megaliths from a rocky eminence, and a pool created near the largest cluster of megaliths hint at the role of sound and water in whatever rituals for the dead that might have taken place here. For megaliths are but monuments to the dead — some of them sepulchral, which once contained the remains of dead people, and others commemorative, in nature.

Much as Hire Benakal is spectacular, and important for understanding megaliths, it is one of hundreds of megalithic sites in Karnataka. On a hill near the village of Doddamolathe in Somwarpet taluk of Kodagu district is another beautiful megalithic site. Remains of several dolmenoid cists are strewn across the hilltop, with a few of the dolmens better preserved than most. The striking feature about the megaliths here is the ring of stone slabs encircling the stone chambers, with a pair of curved slabs forming a portal of sorts aligned with the porthole.

Interestingly, the megalithic site near Doddamolathe is known as Mori Betta locally, deriving from the seemingly ubiquitous folklore attributing the authorship of these monuments to a now-extinct race of dwarves called Moriyas. At Hire Benakal, too, the villagers refer to the megalithic site as Moriyara Gudda, and the megaliths as Moriyara Mane — the houses of the dwarves. Doddamolathe is the largest among several megalithic sites in the surrounding landscape, Morikallu Betta being another impressive site, though ravaged by quarrying activity in its vicinity.

Another extensive megalithic site of Karnataka is at Rajan Kollur, about six km northeast of Kodekal in Yadgir district, and part of a vast ancient landscape containing a Neolithic ashmound and the megalithic stone alignment site at Hanamsagar within a few kilometres. There are dolmens and dolmenoid cists distributed in two clusters, less than a kilometre west of the village. The larger cluster is now fenced in and protected by the Archeological Survey of India, with cultivated fields intervening between it and the smaller cluster. Col Philip Meadows Taylor, who was the political superintendent (1841-53) and later commissioner (1858-60) of Surpur Samsthan, and a keen antiquarian, was the first to report these megaliths, after he visited them in 1850. He recorded nearly 200 dolmens, in one large cluster, of which only about half survive today, the rest having succumbed to agricultural expansion and vandalism.

Meadows Taylor had some of the megaliths opened and found a layer of ash mixed with earth and human bones, along with shards of pottery. Today, most of the dolmens stand vandalised, missing several of their slabs. The dolmens, made of roughly hewn limestone slabs, sometimes have crudely fashioned portholes. The dolmens here vary in size, the largest measuring 4m x 1.75 m and around 1.3m high; while the smaller ones are around 1.8m x 0.75m and only 60cm high. There are even smaller ones, which have been almost obliterated. The megaliths of the eastern cluster sport circular portholes and seem to be dolmenoid cists.

Wanton destruction

One disturbing factor found across all megalithic sites is the wanton destruction which proceeds unabated, often despite being under protection. Quarrying has all but destroyed Mori Kallu, where the surviving dolmens perch on vestigial islands of granite amidst an ocean of destruction.

Although pressure from agriculture and urbanisation takes a toll, most of the damage is from vandals who plunder these ancient structures for suspected treasure within, only to throw away the broken pots containing bone and ash in disgust, when they find nothing valuable within. A typical example was seen at Doddamolathe, where a megalith was freshly vandalised shortly before our visit in 2017.

A plundered megalith is evidence destroyed, as far as archaeology is concerned — evidence which might have yielded valuable insights into the lives of our ancestors, if excavated scientifically by trained personnel. Our megaliths hold the key to understanding the world views, beliefs, rituals and knowledge systems of our forebears from the prehistoric past — those unknown folk who lived in flimsy huts of wattle and daub, but left behind images on rockfaces, which we struggle to make sense of, and expended much energy and effort in building these enigmatic monuments in stone to honour their dead, which were meant to endure centuries after they had vanished.

Little do the vandals realise that therein lies the real treasure.

(The author is with the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru)