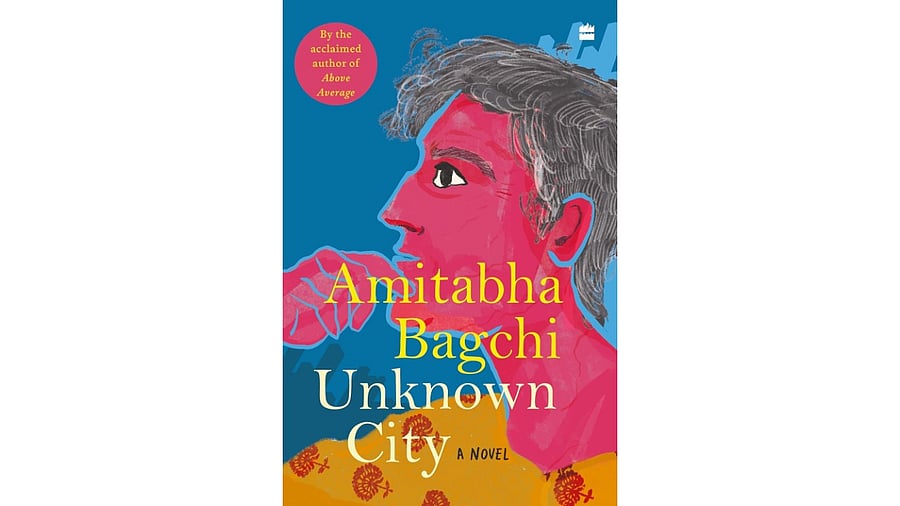

Unknown City

Credit: Special Arrangement

“It’s a numbers game,” says the horny Saxon Ratliff in the first episode of season three of The White Lotus as he leches on four women by the hotel pool. “It’s a numbers game,” says the lovelorn Petro in the criminally underrated Australian comedy series Fisk when explaining his efforts to find a soulmate. “It’s a numbers game,” I tell myself as I reach the epilogue of Amitabha Bagchi’s new novel, Unknown City, and learn how the narrator, Arindam Chatterjee, meets the woman he will marry.

Readers first met Arindam in Bagchi’s debut novel, Above Average. That book, published in 2007, is narrated by the teenage Arindam as he struggles to form a sense of self in the overly masculine and hyper-competitive environs of IIT Delhi. At the start of Unknown City, which is a sequel to Above Average, Arindam is about to turn 50 and is a successful novelist and IIT Delhi professor (much like his creator Bagchi).

Arindam’s first book, the one that launched his writing career, is titled In Crossing This River — the in-universe version of Above Average. He is now writing a book, this book, that is a tale of how he fell in love with, crushed on, or was mildly infatuated with various women in the years 1996 to 2005 when he moved to the USA to pursue his PhD. Talking about numbers: if Above Average had three women characters who had somewhat fleshed-out supporting roles in the coming-of-age story of young Arindam, Unknown City has more than a dozen women who play major and minor roles in the making of the older Arindam.

Reading Unknown City, the question does arise: Do we really need a novel about a straight, middle-aged Indian man excavating his romantic relationships via his memories and a handy email archive? Arindam sets out his argument in favour of such an endeavour in the first few pages, framing this story as an attempt to figure out why things didn’t work out between himself and these women. Unknown City moves back and forth in time reassessing, analysing, and interpreting meanings of gestures, comments, sexual encounters and other interactions through the perspective of Arindam who is aware of how unreliable these memories are as the past is, in his view, a “fluid, changeable mess of half-remembered and incorrectly labelled thoughts”.

To get back to the point (as Arindam frequently says after a not-very-helpful digression from the main narrative), does this novel have any incisive insights into the gender divide and power imbalances that plague even the most equitable heterosexual relationships? Can 315 pages of one man’s exhaustive, granular enquiry into his own evolving sentiments, understanding of women, and trying to divine what his one-time girlfriends or dates may have actually thought of him be compelling enough to hold the reader’s interest?

The short answer is no. Part of the problem lies in the fact that we are so much in Arindam’s head — almost claustrophobically so — that we rarely get the perspective of the women. We hear them quoted in emails or reported speech as scenarios play out in Arindam’s memories. When he moves to California and encounters Lisa on an online dating site and finds her interesting because “her answers made her sound like she had a social conscience”, we aren’t told what those answers were. When they meet in real life, they hit it off because Arindam tells us she “found my jokes funny and I found that she too could deadpan quite smoothly and get a laugh out of me.” The reader, unfortunately, can only surmise what these jokes and deadpan dialogues were. We don’t get to laugh along with Lisa and Arindam or experience the thrill of two people experiencing the first unfurling of mutual desire.

And therein lies the fatal flaw of Unknown City: the lack of humour and eroticism that would have leavened what is one man’s long and meandering story of his various “love failures” (as the Indian police would put it). It’s disappointing that the Arindam of Above Average, with his acute observations of Delhi, ear for dialogue, and ability to convey the overt and hidden erotic tension among hormonal young men has devolved into a middle-aged bore who quotes Urdu poetry and feminist thinkers but seems to have mislaid the unique gifts that made that first book such a refreshing delight.