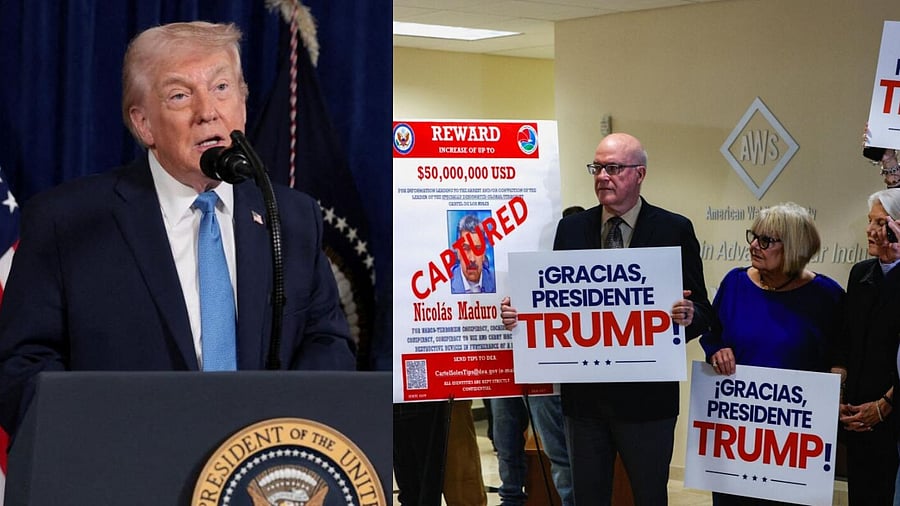

(L) U.S. President Donald Trump | (R) People hold signs reading "Thanks, President Trump!" during a press conference on the U.S. strikes in Venezuela.

Credit: Reuters

United States President Donald Trump has said Washington will “run” Venezuela until a new government is installed, following a US military intervention in Caracas that led to the capture of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. The pair have been flown to the United States to face what Trump has described as “narco-terrorism” charges.

The intervention followed months of military build-up in the region and has drawn sharp criticism from several countries, including Russia, which called the US action an “act of armed aggression” and said the justifications offered were “unfounded”.

The central question now is whether the operation has any basis under international law.

Does the UN Charter permit the use of force?

Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter prohibits states from using force against the territorial integrity or political independence of another country. This prohibition is considered a cornerstone of the post-Second World War international legal order.

Under international law, the use of force is lawful only in limited circumstances: if authorised by the UN Security Council, carried out in self-defence against an actual or imminent armed attack, or undertaken with the consent of the lawful government of the state concerned.

In the case of Venezuela, there was no Security Council resolution authorising US action. Nor has the US demonstrated that it was responding to an imminent armed attack by Venezuela, making a self-defence claim legally weak.

Could consent justify the intervention?

One possible argument is that the intervention was carried out with the consent of Venezuela’s lawful government. The legitimacy of Maduro’s presidency has been questioned internationally, particularly after allegations that the 2024 election was stolen from opposition candidate Edmundo González.

However, the issue of who constitutes Venezuela’s lawful government remains contested. Some states continue to recognise Maduro, while the opposition exercises no effective territorial control. In such circumstances, international law generally requires Security Council authorisation for external military intervention, even if consent is claimed by one side.

Was this merely a law enforcement operation?

The Trump administration has sought to frame the operation as a law enforcement action rather than a military one, describing Maduro as a fugitive wanted by US courts. This distinction matters because law enforcement actions are not automatically treated as “use of force” under the UN Charter.

However, the scale and context of the operation complicate that claim. Reports indicate a significant US troop presence in the region, naval deployments near Venezuela, and a direct operation ordered by the US president targeting a sitting head of state. Taken together, these factors strongly point to a use of force between states rather than a routine law enforcement exercise.

Why does this matter?

Even if Maduro’s removal is welcomed by some, legality does not depend on outcomes. If powerful states act outside the law without consequences, the prohibition on unilateral military action risks being hollowed out.

International law does not cease to exist because it is violated. But its survival depends on whether states are willing to call out breaches, including when committed by allies or global powers and insist that rules apply equally to all.