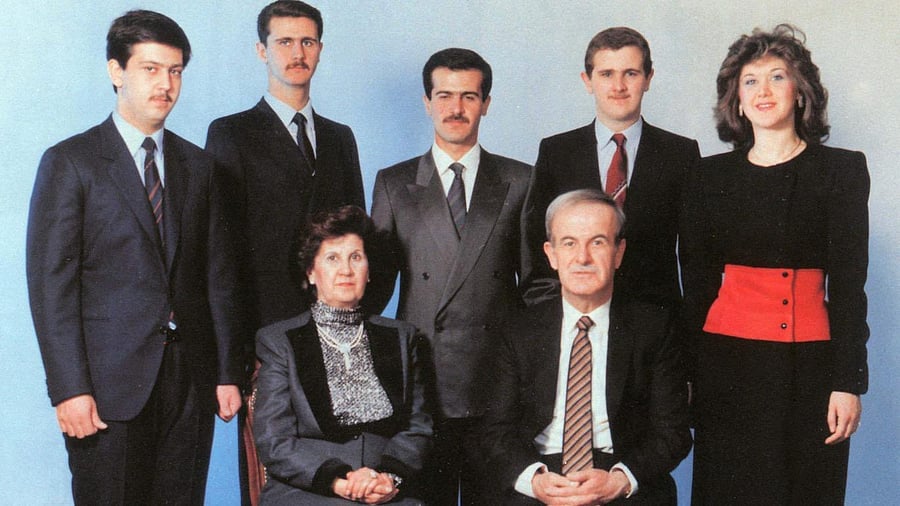

The Assad family dynasty

Credit: X/@realMaalouf

Over decades, ghastly, chilling images from Syria have cemented the Assad family’s legacy of savagely oppressing the country’s population.

In 1982, photos showed the pulverized central city of Hama after the regime bombed and bulldozed a Muslim Brotherhood uprising, leaving up to 20,000 people dead.

In 2013, images emerged of hundreds of ghostly pale bodies in a rebellious Damascus suburb, victims of one of the government’s chemical weapons attacks. Many of the dead were children.

That same year, a former military photographer smuggled thousands of photographs out of Syria documenting how political prisoners had been starved, beaten and subjected to brutal torture — their eyes gouged out or their genitals mangled.

“These people did not care; the leadership cared nothing about the Syrian people,” said Andrew Tabler, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and a former US government official on security issues. “They launched Scud missiles against their own people — who does that? — while the chemical weapons were a sign of just how far they would go to hold on to power.”

Syrians sometimes said the Assads were like the fictional Corleone crime family, but with secret police networks attached — a ruthless clan of brothers and cousins who dominated the political system, the military, the economy and even the exports of illegal drugs. Much of the country lived in fear.

“They were not running a country with a history of 5,000 years of civilization,” said Ayman Abdel Nour, a former college friend of President Bashar Assad who joined the opposition out of disgust over the lack of reform. “They were running it like the Mafia, as if it was a private estate, the whole country was their backyard inherited from their father.”

After World War II, Syria was known as the most unstable country in the Middle East, with at least eight coups carried out from the end of French colonial rule in 1946 until 1970.

Hafez Assad, an air force officer, put an end to that after he seized power that year, rebuilding the country as a Soviet-style, single-party police state that exploited sectarian differences among Syria’s mosaic of religious and ethnic groups to retain power.

He set about turning the country into a power to be reckoned with in the Middle East, launching the 1973 war against Israel in conjunction with Egypt and exerting control over neighboring Lebanon and the Palestinian political leadership there to end its long-running civil war. In power for 30 years, he built fearsome, overlapping internal security agencies, with thousands of victims disappearing into his prisons.

When he died in 2000, the government changed the constitution to lower the age needed to be president to 34 from 40 so that his son Bashar could take over. Bookish, shy, socially awkward and trained as an eye surgeon, Bashar Assad became the designated heir only after his swashbuckling older brother, Basil, died.

Bashar Assad, with his glamorous, Syrian-British wife, Asma, announced plans for political and social reform that he soon abandoned when he realized it would require dismantling his father’s legacy. “To both father and son, making concessions was not acceptable,” said Randa Slim, a senior fellow with the Middle East Institute in Washington. “Eventually that is what brought Bashar down.”

In 2011, amid the uprisings across the Middle East, Syria’s large youth population rose up against Assad, incensed at the lack of democracy, jobs and overall freedom.

The violent government crackdown transformed what had been nonviolent street demonstrations into a bloody civil war.

“Bashar came to power with many doubting that he had the will to rule Syria with the kind of iron fist that his father did,” said Firas Maksad, a Syria expert and the director of strategic outreach at the Middle East Institute. “He had a chip on his shoulder and was out to prove that he, in fact, could be his father’s son. And in some ways, he ended up exceeding his father’s brutality.”

The Assads had built a power base from their community of Alawites, a minority sect that is an offshoot of Shiite Islam. Bashar Assad’s supporters adopted the slogan “Assad or we burn the country.” Millions of refugees fled Syria to surrounding countries, while an estimated 500,000 people were killed or went missing.

But Bashar Assad was less shrewd than his father. As the rebels, dominated by Sunni Muslim jihadi groups, seemed on the verge of overthrowing him in 2015, he turned to Iran, Hezbollah and Russia to prop up his government.

For a time, they did. He proved unable to manipulate them, however, and his obstinate personality soon alienated his allies. With Iran and Hezbollah severely weakened by their conflicts with Israel, and Russia concentrating on its war in Ukraine, there was no force willing or able to prop him up anymore. His own army melted away, even as he made a last, desperate attempt to shore up their support by ordering a 50 per cent pay raise last week.

The rebel forces that grew out of the civil war finally managed to overthrow him, opening many of the notorious prisons in which his family’s government had for years jailed, tortured and executed political prisoners. The rebels themselves appeared surprised by the speed and ease with which the seemingly entrenched Assad dynasty finally crumbled.

Still, after more than a decade of fighting, Syria’s main cities lie in ruins and the male population between the ages of 20 and 40 has been decimated. “Both the infrastructure and the human capital are totally destroyed,” Abdel Nour said.