Anoop Babani and his wife Savia Viegas lived in Mumbai for most of their professional life and they chose to move to a quiet little village in Goa in 2005 after retirement. Well into their sixties, Anoop and Savia knew that the change wasn’t going to be an easy one, but the thought of exploring a new place, its culture and food habits was exciting. The couple nursed a deep interest in cycling and cinema and they found new meanings in both their passions in their new home.

A few months after moving to Goa, Anoop took to cycling and soon Savia joined him. The broad roads and traffic-free stretches made Goa every cyclist’s paradise. Anoop’s routine took an unusual turn after he had a fall in 2017 and was confined to the bed for a week. Barred from cycling for weeks, Anoop chose to read about it. He was curious to trace the history of the cycle and wanted to discover the early cyclists and what ignited their interest. The couple began reading and their extensive research revealed that well-to-do Indians, mainly in Bombay and Calcutta, took to cycling in the 1890s.

Chronicle of adventures

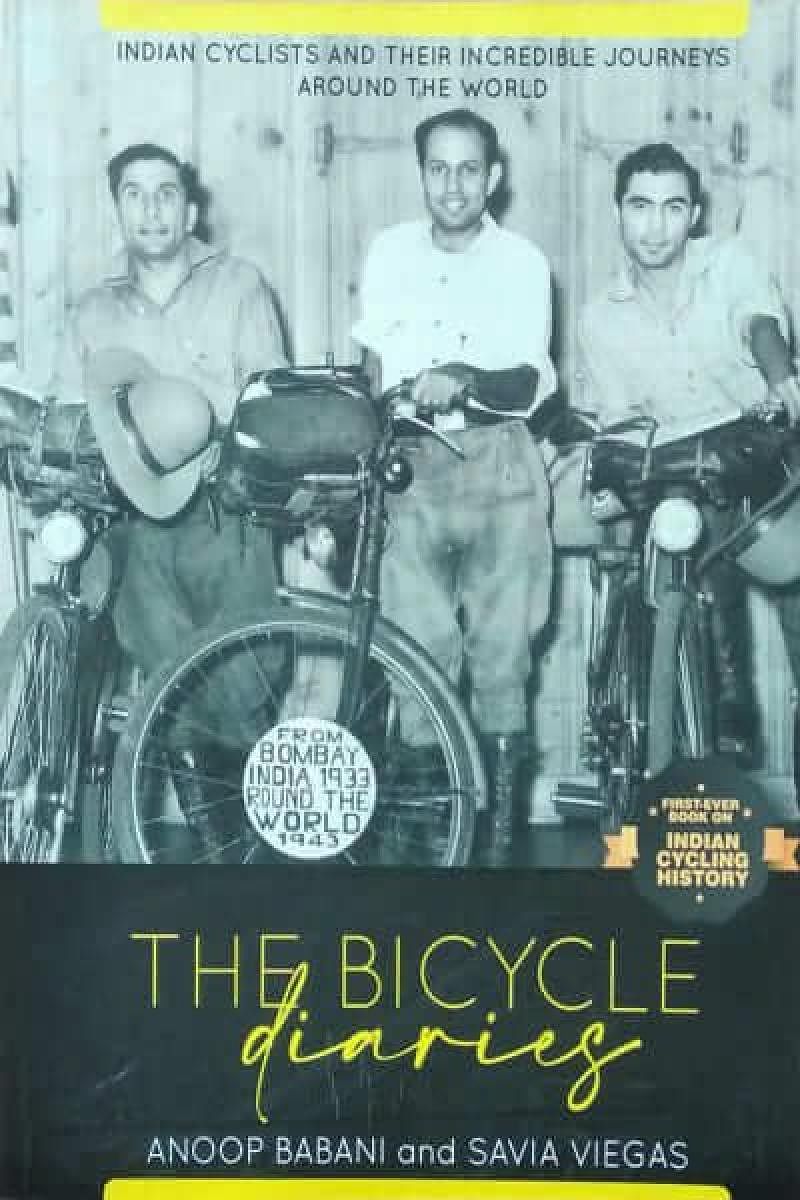

Anoop and Savia began reading and gathering an exhaustive amount of information and photographs about the early cyclists from their families and friends. After spending four years on research for the book, they have documented their findings about the history of cycling in India in ‘The Bicycle Diaries’, the first ever book on Indian cycling history. The book looks at how 12 Indian cyclists undertook five separate global cycling journeys, and eight of them succeeded. “We began reading about the first journey and one led to another. We started meeting people who took us through the third and fourth journeys. We were surprised to know that there was so much history and adventure, but very little written about it,” says Anoop.

The common thread among the early cyclists was that most of them were from the Parsee community. In the first chapter, Anoop looks at how the bicycle came fairly early to India, aided by Colonial rule and the subsequent imports of Britain-made cycles. “Given its affordability, within a decade of their introduction, cycles were widely used by the working class for daily commute,” writes Anoop. He goes on to talk about how cycles soon became the rich man’s pastime and how Parsees became the epicentre of India’s biking adventures.

How did the Parsees take to cycling so easily? Anoop tells DHoS, “The Parsees were the most Europeanised community in India during British times. They were hobnobbing with the English and because of their privileged position in the society, they took to these sporting activities naturally.”

A golden age

Anoop further writes about how the 1890s became the ‘Gilded Age of Cycling’. “It became a transformational force for change and a symbol of an avant-garde lifestyle. Cheaper than a horse and more adventurous than train travel, the free-spirited cyclists could ride faster and pedal off into the unknown,” writes Anoop.

Thomas Stevens, an American peddler, was the first to cycle across the globe. This inspired many to hit the peddle in a big way. In India, particularly in Mumbai, the craze for cycling had caught on. In 1923, the Bombay Weightlifting Club was set to pack off six of their best cyclists on a cycling tour around the world. “Of the six, Hakim, Bapasola and Bhumgara became the first Indian globetrotters to complete the most arduous journey of their lives, cycling 71,000 km over four-and-half-years,” writes Anoop, who goes on to elaborate how they survived the harshest of conditions to successfully complete the expedition.

In the first chapter, Anoop explores the adventures of two other cyclists — Scouter F J Davar , an Indian and Gustav Sztavjanik, who cycled together for seven years. Anoop says that the most exciting part of writing the book was to be able to see the world through their eyes. “Most of the cyclists had a perceptible idea of what was going on around the world. And they wrote down their experiences and carefully documented what they saw. There were those who rode through Afghanistan and met Russian refugees. Here, we get a peek into the life of Russian refugees and how they became so. We know through their narration their understanding and prediction of who will emerge strong after the two world wars,” explains Anoop.

Anoop and Savia have also retraced the journeys of other cyclists such as Gandhi, Kharas and Shroff, who cycled five continents between 1933 and 1942 and Mody who cycled 84,000 kilometers across five continents and finally Vajifdar who cycled between 1934 and 1938. “Many cyclists, who have chronicled their journeys, wrote about issues like widespread prostitution in European cities because of the war. They talk about the migration from the Soviet Union to Afghanistan after Stalin came to power. We also read about the encounters of the cyclists who participated in the Nazi rallies. Most cyclists were at the heart of chaotic, exciting and dangerous situations around the globe. They were either witnesses or participants in some form. It shows what kind of crazy adventures they had and the troubles that they had courted during that time,” explains Savia.

The book relives the journey of the last cyclist Adil Govadia, who coincidentally lives in Bengaluru and decided to ride his way to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, “Govadia’s journey was born out of frustration and inspiration, both at once. He was also among the few Indians who saw India’s track and field queen P T Usha lose the bronze medal by 1/100th of a second. Govadia cheered Usha till his voice went hoarse,” writes Savia.

Anoop and Savia say that chronicling the journeys of these cyclists would not have been possible without the generosity of the families and friends of each of the cyclists, who shared an exhaustive amount of rare material and photographs. “Our first book has sold exceptionally well. In our second book, we want to explore the social and economic aspects of cycles. We want to look at who or what killed cycling. Indians took to cycling very well, but why didn’t it catch on and why did we give it up in favour of motorcycles and cars. We hope to find answers to these in our second book,” says Savia.

For copies of the book, contact saxttibooks@gmail.com