The study and interpretation of our history is no longer the province of scholars and academicians. Indian history is being written and rewritten by demagogues and propagandists, recast by people who want to shape the present and the future in the mold of their own versions of the past. No one political ideology has a monopoly in this respect — left, right and everyone in between has a preferred vision of history and these perspectives shape how we vote, interact with our fellow citizens and respond to laws and lawmakers.

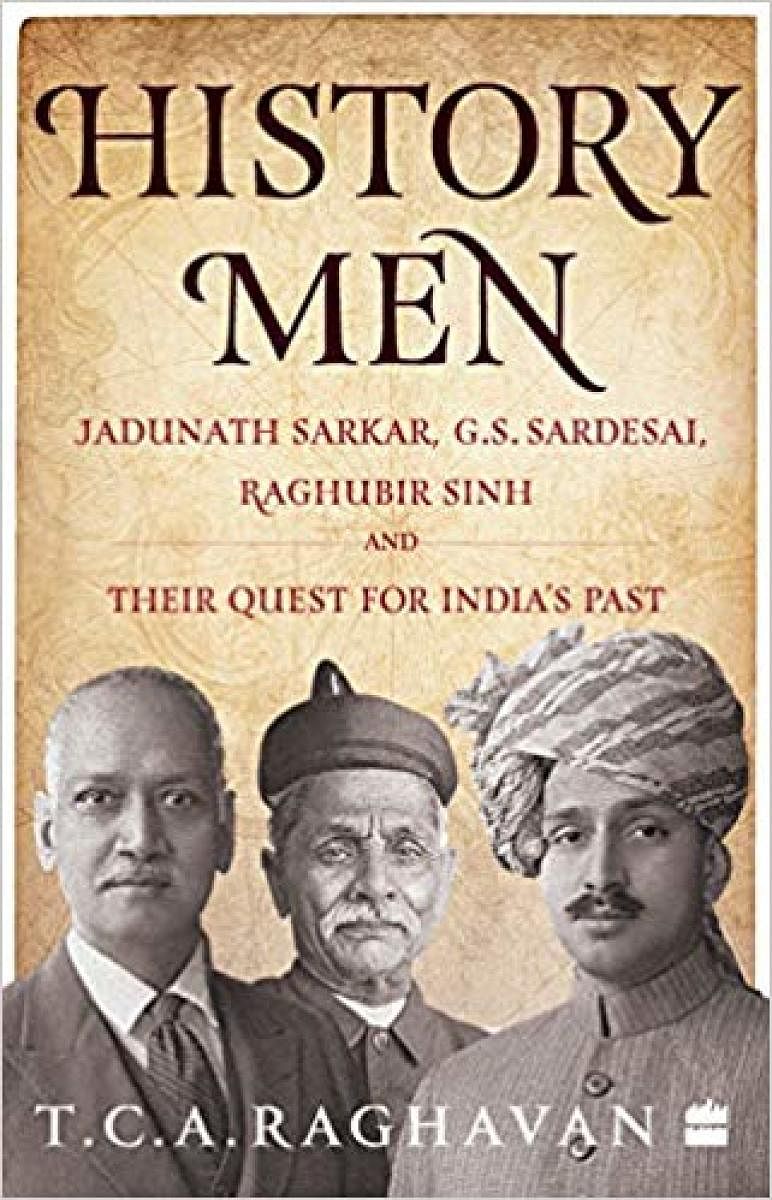

At such a time, a book like historian and diplomat Raghavan’s History Men comes as a much-needed breath of fresh air, retelling for us the lives and intertwined studies of three men who collectively helped bring rigour and objectivity to the study of Indian history over the course of the late 19th and much of the 20th century. The three men were Jadunath Sarkar, an eminent scholar of the Mughal era, G S Sardesai, who focused on Maratha history and Raghubir Sinh, a scion of aristocracy, who made Rajput history his area of focus. Sardesai functions as a linking element, carrying on extensive lifelong correspondences with both colleagues.

Raghavan sorts through their letters to tell us of the challenges they faced — Sardesai, for instance, was often criticised for approaching Shivaji as another historical figure, to be studied dispassionately like any other, rather than the subject of hagiography. Similarly, Sarkar had to sift through earlier sources that were written to please either Mughal or British rulers, finding the thread of a true narrative woven through the excesses and omissions of earlier works, but more importantly, through primary sources. Again, post and pre-independence, depending on the government for assistance was always a struggle.

Chasing down facts

At the same time, their focus remains on history itself, on chasing down elusive facts, poring over obscure manuscripts to establish details like the exact date of a particular battle to the nth degree of certitude. There is a touching exchange where, amidst concerns over Sardesai’s health and morale, Sarkar also writes to Sinh about their conclusions on the date of this first major victory of Aurangzeb against Shah Jahan and Dara Shukoh.

We can see how the shape of Indian history has always been ideologically contested from the reactions to Sarkar’s groundbreaking work on Shivaji from sections of the Maratha community. In a letter to Sarkar, Sardesai outlines some of the camps contesting the narrative; ‘a number of linguistic groups, each with conflicting traditions & aspirations...subsections like the Brahmin BSM, the non-Brahmin Shivaji memorial, the Peshwa Daftar…’ and so on. Some of the groups and alliances may have changed, but this struggle to shape the past to suit the needs of the present is familiar to anyone who has paid attention to recent times.

The three did not always see things the same way, differing in their views on aspects of Maratha expansion and the roles played by specific personages. Yet, all three were united by a commitment to going to primary sources, plunging into the raw materials of historiography and finding the best evidence available. Their debates hinged on the assessment of available evidence, on the authenticity of different sources, not on preconceived notions and narratives.

Meticulous work

How these men loved the nitty gritties of historiography! Here is Sarkar waxing eloquent on the Jaipur Archives; ‘the historian who has such a rich variety and profusion of the pure raw materials of his craft at his command, may well congratulate himself on holding a position unmatched elsewhere in the realm of Indian historiography’. And yet, access to these treasures was never easy as Sarkar wrote to Sinh in 1935; ‘the only way to utilise these materials...is (first) to get the Maharajah’s full and unreserved permission...but I refuse to go to Jaipur if the officers thwart and insult me (as they did in 1928) by their suspicious attitude…’.

In an epilogue, Raghavan points out the commitment to the facts, whatever they may be, that all three men displayed, even though Sardesai, in particular, intended to justify the actions of the Marathas in his work. Despite this, and through his exposure to the other two men, he came to share in their commitment to ‘an impulse of dissent which they accepted as being integral to history writing’. Raghavan refers here to the skeptical impulse, not to demean or demonise, but blow away the cobwebs and dust of ideology and pride and present the story of our history, unadorned and clear, to the best of our knowledge and ability. A timely message, and one I hope readers of this meticulous, lucid book will take to heart.