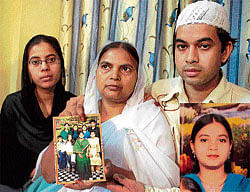

Fighting with all the odds pitched against her, it was sheer ‘will power of a mother,’ that drove her, relentlessly battling poverty and stigma, all the way to the hallowed pedestal of justice. She has become an epitome of a soft-spoken fighter from Bihar. She is Shamima Kausar, mother of the 19-year-old Ishrat Jahan murdered by Gujarat police officials.

Gashes of lights glisten on the black walls of the low-ceilinged water-soaked entrance of a building raining down peeled cement.

The staircase to the fourth-floor two-room apartment where Shamima currently stays, says, “I came to Mumbra (a sea-side town 40 km away from Mumbai) from Patna in 1992 and within two months I was a witness to the horrors of danga fasad (riots.)” It takes a lot of soft persuasion to make her tell about the wounds inflicted on her by the State and society.

“Hum saaf suthre aadmi hai aur main apni beti ka naam saaf dekhna chahti thi. Woh vapas toh nahi aayegi par maien insaaf chahti thi.” (We are clean people and I wanted to clear my daughter’s name. She will never come back but I wanted justice.)

For seven years, the iron-willed lady hailing from a small mohalla in Patna, making trips to Ahmedabad in Gujarat, in pursuit of an elusive justice was not easy. Moving gingerly amongst the cold indifferent law officials, demanding an enquiry into her daughter’s death in a so-called police encounter would have made even the toughest crusader shrink in a state with archives saturated with bitter history of communal partisanship.

“My son Anwar used to come with me. He was 14 when they killed my daughter. I don’t know how I managed the family. My husband died in 2002 and even though I was taking tailoring and embroidery work, Ishrat had also started contributing to the household income by taking tuitions of school children in the house only. My eldest daughter also was taking tailoring work.”

“After her murder we just stopped living. ’Zinda lash bangaye tha hum’ (We had become living corpses). People used to avoid us and we also stopped interacting with others. Since her death I don’t know how we managed to live. It was just on a day-to-day basis that we lived. And amidst this I even trekked to Ahmedabad for the hearings.”

Since Ishrat’s murder, Shamima and her six children shifted thrice though in the same locality where even today people avert their eyes and feign ignorance on being asked about Ishrat’s family whereabouts. Each house shift was to accommodate the depleting income and secure education for her children.

For one year, “I just lived in isolation. Thereafter, my eldest daughter used to take tuitions of school children. The numbers slowly started dwindling. Thankfully, my embroidery work continued and some women-oriented social organisations helped me financially and also provided emotional support,” Shamima says adding, “now my son Anwar has learnt computers and has started working.”

Twenty-one-year-old Anwar sitting near his mother quietly looks up with a strain of emptiness in his eyes and pain in his voice.