Africa racing to defuse population bomb

In a quarter century, at the rate Nigeria is growing, 300 million people – a population about as big as that of the present-day United States – will live in a country the size of Arizona and New Mexico. In this commercial hub, where the area’s population has by some estimates nearly doubled over 15 years to 21 million, living standards for many are falling.

Lifelong residents like Peju Taofika and her three granddaughters inhabit a room in a typical apartment block known as a ‘Face Me, Face You’ because whole families squeeze into 7-by-11-foot rooms along a narrow corridor. Up to 50 people share a kitchen, toilet and sink – though the pipes in the neighbourhood often no longer carry water.

At Alapere primary school, more than 100 students cram into most classrooms, two to a desk. As graduates pour out of high schools and universities, Nigeria’s unemployment rate is nearly 50 per cent for people in urban areas ages 15 to 24 – driving crime and discontent. The growing upper-middle class also feels the squeeze, as commutes from even nearby suburbs can run 2 to 3 hours.

Last October, the United Nations announced the global population had breached 7 billion and would expand rapidly for decades, taxing natural resources if countries cannot better manage the growth. But nearly all of the increase is here in sub-Saharan Africa, where the rise in population far outstrips economic expansion. Of the roughly 20 countries where women average more than five children, almost all are in the region.

Elsewhere in the developing world, in Asia and Latin America, fertility rates have fallen sharply in recent generations and now resemble those in the US – just above two children per woman. That transformation was driven in each country by a mix of educational and employment opportunities for women, access to contraception, urbanisation and an evolving middle class. Whether similar forces will defuse the population bomb in sub-Sarahan Africa is unclear.

“The pace of growth in Africa is unlike anything else ever in history and a critical problem,” said Joel E Cohen, a professor of population at Rockefeller University in New York City. “What is effective in the context of these countries may not be what worked in Latin America or Kerala or Bangladesh.”

Across sub-Saharan Africa, alarmed governments have begun to act, often reversing longstanding policies that encouraged or accepted large families. Nigeria made contraceptives free last year, and officials are promoting smaller families as a key to economic salvation, holding up the financial gains in nations like Thailand as inspiration.

Nigeria, already the world’s sixth-most populous nation with 167 million people, is a crucial test case, since its success or failure at bringing down birthrates will have outsize influence on the world’s population. If this large nation rich with oil cannot control its growth, what hope is there for many smaller, poorer countries?

“Population is key,” said Peter Ogunjuyigbe, a demographer at Obafemi Awolowo University in the small central city of Ile-Ife. “If you don’t take care of population, schools can’t cope, hospitals can’t cope, there’s not enough housing – there’s nothing you can do to have economic development.”

Trying hard to keep up

The Nigerian government is rapidly building infrastructure but cannot keep up, and some experts worry that it, and other African nations, will not act forcefully enough to rein in population growth. For two decades, the Nigerian government has recommended that families limit themselves to four children, with little effect.

Although he acknowledged that more countries were trying to control population, Parfait M Eloundou-Enyegue, a professor of development sociology at Cornell University, said “many countries only get religion when faced with food riots or being told they have the highest fertility rate in the world or start worrying about political unrest.”

In Nigeria, experts say, the swelling ranks of unemployed youths with little hope have fed the growth of the radical Islamist group Boko Haram, which has bombed or burned more than a dozen churches and schools this year.

Internationally, the African population boom means more illegal immigration, already at a high, according to Frontex, the European border agency. There are up to 400,000 undocumented Africans in the US.

Nigeria, like many sub-Saharan African countries, has experienced a slight decline in average fertility rates, to about 5.5 last year from 6.8 in 1975. But this level of fertility, combined with an extremely young population, still puts such countries on a steep and disastrous growth curve. Half of Nigerian women are under 19, just entering their peak childbearing years.

Statistics are stunning. Sub-Saharan Africa, which now accounts for 12 per cent of the world’s population, will account for more than a third by 2100, by many projections.

Because Africa was for centuries agriculturally based and sparsely populated, it made sense for leaders to promote high fertility rates. Family planning was introduced in the 1970s by groups like Usaid. Later on, money and attention were diverted from family planning to Africa’s AIDS crisis.

“Women in sub-Saharan Africa were left behind,” said Jean-Pierre Guengant, director of research at the Research Institute for Development, in Paris. The drastic transition from high to low birthrates that took place in poor countries in Asia, Latin America and North Africa has yet to happen here. That transition often brings substantial economic benefits, said Eduard Bos, a population specialist at the World Bank.

At his concrete home in the town of Ipetumodu, Abel Olanyi, 35, a laborer, said he has four children and wants two more. “The number you have depends on your strength and capacity,” he said, his wife sitting silently by his side.

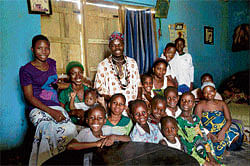

Large families signal prosperity and importance in African cultures; some cultures let women attend village meetings only after they have had their 11th child. And a history of high infant mortality, since improved thanks to interventions like vaccination, makes families reluctant to have fewer children.

In Asian countries, women’s contraceptive use skyrocketed from less than 20 per cent to 60 to 80 per cent in a few decades. In Latin America, requiring girls to finish high school correlated with a sharp drop in birthrates.

But contraceptive use is rising only a fraction of a percent annually – in many sub-Saharan African nations, it is under 20 per cent – and, in surveys, even well-educated women in the region often want four to six children. “At this pace it will take 100-plus years to arrive at a point where fertility is controlled,” Guengant said.

The United Nations estimates that the global population will stabilise at 10 billion in 2100, assuming that declining birthrates will eventually yield a global average of 2.1 children per woman. At a rate of even 2.6, Guengant said, the number becomes 16 billion.

In Nigeria’s desperately poor neighbour, Niger, women have on average more than seven children. But with land divided among so many sons, the size of a typical family plot has fallen by more than one-third since 2005, meaning there is little long-term hope for feeding children, said Amadou Sayo, of an aid group.

Birthrates have edged down to about four children per woman in Kenya, Ethiopia and Ghana.