ISTOCK

Before glass sparkled or steel shone, before skyscrapers touched the sky or plastic filled our shelves, there was clay. Ordinary, earthy, squishy clay. You might think of it as something you use in art class or spot in a potter’s wheel demonstration—but this humble substance has shaped human civilisation in more ways than you can imagine.

The story of clay begins deep underground. Clay is made up of fine-grained particles formed when rocks like granite slowly break down over time. Rain, wind, and ice work together to grind these rocks into soft sediments, often settling in riverbeds and lakes. If you've ever walked barefoot through sticky mud after a rainstorm, you've felt the slippery smoothness of natural clay. It's messy, but it's also magical—because with the right amount of water and heat, clay becomes strong, durable, and endlessly useful.

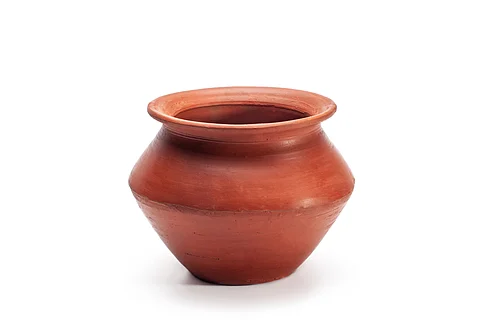

Humans discovered that magic thousands of years ago. Archaeologists have found clay pots and figurines that are over 10,000 years old. The first people to use clay weren’t aiming to create art—they just needed something to carry water, store grain, or cook food. In fact, some of the oldest surviving cooking pots were made from hand-shaped clay, dried in the sun and hardened in open fires. Imagine someone thousands of years ago, sitting by a fire, watching their creation turn from mud to solid—it must have felt like witnessing a miracle.

Then came the potter’s wheel. Invented around 3,000 BCE in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), the wheel allowed people to shape clay faster and more precisely. This single invention changed everything. Clay wasn’t just functional anymore—it became beautiful. Ancient Egyptians created delicate blue-glazed pottery, the Greeks painted stories onto their amphorae, and Chinese artisans crafted elegant porcelain that travelled the world along ancient trade routes.

But clay wasn’t only for pots and plates. It became the world’s first writing surface. Long before notebooks and iPads, ancient Sumerians pressed wedge-shaped marks into soft clay tablets using a stylus made from reed. This writing system, called cuneiform, recorded everything from trade deals to myths. Once the tablet dried, it could last for thousands of years. Thanks to clay, we know how some of the earliest cities were run, what people worshipped, and even what they ate for dinner.

Fast forward a few centuries, and clay started building homes—literally. People in ancient civilisations such as those in the Indus Valley and parts of Africa began mixing clay with straw to make bricks. When dried and fired, these bricks became the building blocks of houses, temples, and city walls. Even today, clay bricks are used across the world for their strength and ability to keep homes cool in hot climates.

In the world of science and medicine, clay found yet another purpose. In ancient times, healers noticed that certain types of clay could soothe skin rashes or be used to clean wounds. Clay has absorbent properties that can draw out toxins, and some cultures still use it today for skincare and natural remedies. Even in modern labs, scientists are studying how clay might help remove pollutants from water or act as tiny containers for delivering medicines inside the body.

And of course, there’s the art. From sculptures in temples to handmade bowls painted in bright glazes, clay has allowed people to express their creativity for centuries. It’s not just about making something pretty—it’s about storytelling, tradition, and connection. Every fingerprint left in clay is a reminder of the hands that shaped it, whether they belonged to a potter in ancient China or a school student in a ceramics class.

The Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest law codes in the world, was first carved into clay tablets.

Clay has a property called thixotropy — it remembers the pressure and force applied to it, which is why potters need steady hands.

Bentonite clay can absorb many times its weight in water, making it useful in everything from drilling to cosmetics.

Long before metal pots existed, people cooked meals in clay vessels placed directly over fire.

Certain types of clay, like kaolin, are still used in tablets and syrups to soothe upset stomachs.

Scientists study ancient clay layers to understand Earth’s past climate and environmental changes.

Parrots and elephants in the wild eat clay to detox their bodies and get essential minerals.

Clay minerals help filter and insulate materials used in satellite dishes and communication devices.

Ancient Sumerians used clay tablets to invent cuneiform — one of the earliest writing systems in the world.

Certain clays can absorb oil, bacteria, and toxins, which is why they’re still used in face masks and soaps.

The world’s oldest ceramic artefacts, made from clay, are over 18,000 years old and were found in China.

If it gets too dry or too wet, clay can crack or collapse — potters need perfect timing to shape it right.

Porcelain is made from kaolin clay, which is prized for its smoothness and pure white colour when fired.

Civilisations like the Indus Valley used sun-dried clay bricks to construct homes, baths, and granaries.

The ocarina, a wind instrument found in many ancient cultures, is often made from fired clay.

Its hue depends on minerals — iron-rich clay turns red, while calcium-rich clay appears white or grey.