In Egypt, the world built two mountains for a monument. To find out more about this miracle of co-operation, we went from Cairo where the Nile flowed to where its strength had been tapped: Aswan. Here, Gamal Abdel Nasser’s High Dam towered 40 metres out of the fox-pelt dunes of the desert. At its base, the growling complex of hydroelectric generators pumped uninterrupted power into Egypt. On the other side, the enormous reservoir called Lake Nasser stretched for 500 km into the Nile valley. But, as the dam grew, its waters began to lap at the feet of the magnificent pharaonic temples, thousands of years old, threatening to submerge them forever. Egypt sent a frantic appeal to UNESCO and many nations pooled their resources to save the 14 great temples from certain destruction. Their combined efforts resulted in what is, undoubtedly, the world’s greatest work of conservation: the raising of magnificent monuments from certain inundation and destruction.

We boarded a guarded caravan of tourist vehicles to speed 280 km down a desert road. An armoured vehicle led us; another drove in the middle of our motorcade; a third brought up the rear. “You can never be too sure in this land,” said a Libyan fellow passenger, smiling dismissively and, possibly, rather too smugly. Beyond our windows, the landscape unreeled, dun-coloured, sere and monotonous with not even the wind to ruffle the great sea of sand. The only unusual thing we saw on this glare-filled road were curious hillocks shaped like well-defined pyramids. We had not read anything about these striking rock formations. Did the pharaohs draw inspiration for their massive mausoleums from these alien Nubian knolls?

We were in Nubia, whose people differed markedly from the ancient Egyptians, and stoutly resisted the takeover of their Nile-enriched lands by the armies of the pharaohs. In fact, the monuments we were going to see had been created to awe Nuibians with the power and majesty of the great Egyptian monarch and his beautiful queen.

This is a time-honoured ploy of despots: to build towering monuments to impress the people with god-like power of the ruler and hope they will be too scared to revolt. Today we use the media to create a similar illusion.

At the end of the long journey, our convoy drove into a hamlet green with palm trees and Nile-nurtured foliage. It resembled a pleasant Haryana Tourism complex in an otherwise arid landscape. Yellow and pink flowers blossomed extravagantly, pollen drifted like living dust from feathery thorn trees making some of our fellow tourists sneeze. We were all shepherded into a modern Reception Centre with scale models of the Great Rescue, a coffee shop with hookahs on demand, and stacks of attractive souvenirs, many of which were, unashamedly, ‘Made in China’.

Journey begins

But the tawdriness of the trinkets did nothing to diminish the stupendous achievement of the great conservationists of the world who had worked here under the banner of UNESCO. We set out from the air-conditioned comfort of the reception building to see this modern wonder for ourselves.

“They say, here, that it’s greater than the pyramids,” said a large American dowager in a flat Great Plains accent. Her face glowed with sweat in the speckled shade of a large straw hat and she held up a limp travel brochure. She didn’t expect an answer and waddled away, her shadow a faithful black puddle at her feet.

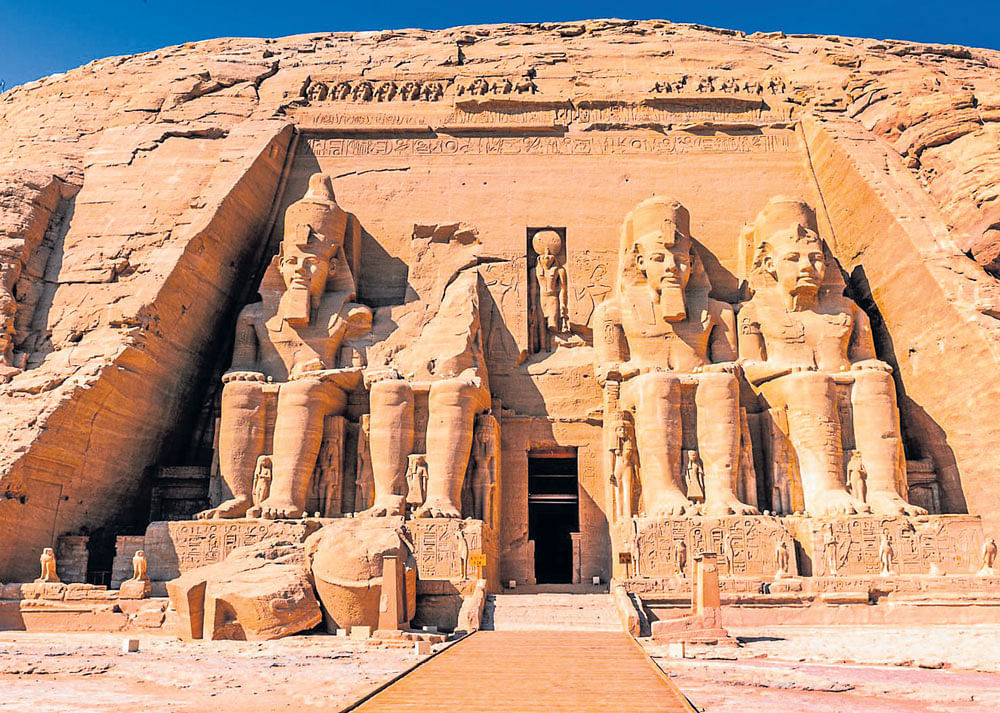

The sun hammered down mercilessly and the trudge around a hulking rocky hillock was long and tiring. But it was worth it. Eventually, there, ahead of us, in a huge amphitheatre of rock-cut cliffs facing the azure waters of Lake Nasser, stood the unforgettable monuments of Pharaoh Rameses II. He had built them to immortalise himself and his beloved principal wife, Nefertari. They were overpowering, unreal: four seated figures of the god-king towered 20 metres high, flanking the entrance to his temple, dwarfing visitors to ant-size by comparison. We were gripped by a sense of unreality when we looked across at the massive rock-cut temples, with their 20-metre-high seated statues guarding the entrance to Rameses’s shrine. Like many rulers, down to our age, he believed in his own divinity and had deified himself.

We clambered up to the entrance and stepped in. It was cool, inside the mountain, but even here tall statues of the king rose depicting him as the god Osiris. The floor sloped gently up, the size of the chambers deceased resembling the dark garbhagrihas, the womb-like sanctums of south Indian temples. In fact, it all felt strangely familiar, but it was only when a small group of Indian tourists passed us that we realised why. A faint fragrance of sandalwood triggered the memory. The carvings on the walls, the increasing feeling that we were entering a mysteriously sacred cavern, all conjured up the same awe we have experienced in our many visits to the towering temples of southern India. The architecture of those great places of worship has developed, slowly and uninterruptedly, over millennia, possibly evolving from the early cave dwellings of revered ascetics.

The resemblance between the two places of worship, separated by time and space, could be because of that mysterious recollection sometimes referred to as ‘racial memory’. Some scholars believe that our Dravidians are of the same race as the pharaonic people. We have noticed that they even dressed alike, in mundus formally worn down to the ankles, but tucked up while working.

We emerged into the sunlight again, blinking and blinded by the glare.

Queens’ corner

A little further to the north was a smaller rock-cut temple dedicated to Hathor, the goddess of love, and to the pharaoh’s favourite wife, the elegant Nefertari. The pharaonic families, apparently, observed an exclusive caste system. As semi-divine beings, they were often restricted to marrying their own brothers and sisters though we don’t know if Rameses II and Nefertari were siblings. We stood in the shade of a tree and looked back at the great cliff into which these temples had been carved. We realised, then, that this stupendous feat of architectural engineering had been done in that distant age when the nomadic Indo-Iranians were establishing their society in northern India, the Rig Veda was being composed, and the first permanent temples had not been built in our land.

In fact, even the temples that rose before us had not been carved here. The place where ancient Egyptians had used picks, shovels and hand-hammered chisels to create these wonders has been submerged. Before that had happened, conservationists had cut the original monuments into blocks, raised them up, fitted them together, and then built two artificial mountains around them to replicate their original ambience. All this had been done with such precision that at the two solstices, when the sun crosses the Tropic of Cancer, its light shafts in through 65 metres, into the heart of the mountains, and illuminates three of the four figures in the sanctum for five minutes. The fourth figure, Ptah, remains in shadow: he was the god of darkness.

That was also how it had been in their original temple, now just an empty, flooded, cavern under the blue waters of Lake Nasser.

Deccan Herald is on WhatsApp Channels| Join now for Breaking News & Editor's Picks