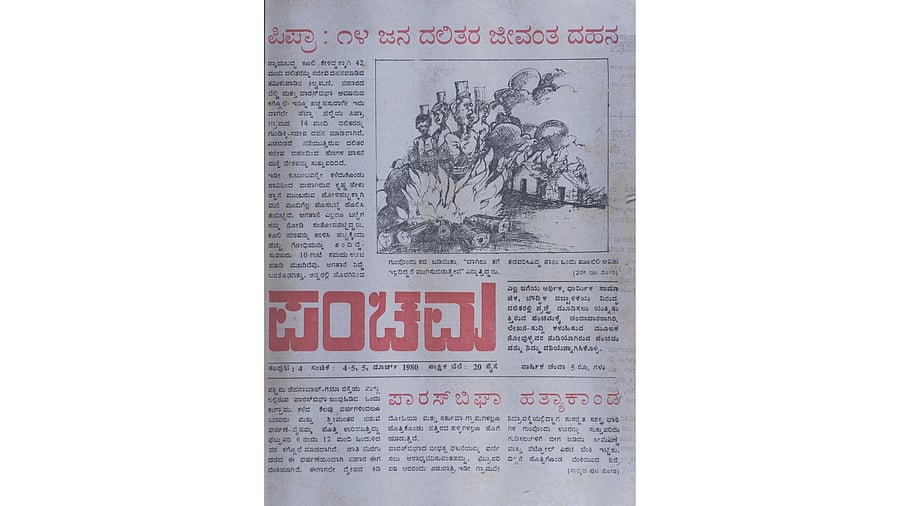

Panchama, a fortnightly newspaper, aimed for total social transformation and the annihilation of caste. Photo by author

The early 1970s were a crucible of change for Karnataka and for India as a whole. Amidst the political turbulence of the Emergency, land reforms and the Boosa Chalavali (a Dalit-led movement sparked after a minister called Kannada literature “boosa” or cattle fodder), a new consciousness was awakening among Dalit and other marginalised communities. In this charged atmosphere, the Dalit community sought avenues to assert their identity and rights. It was in this context that the fortnightly newspaper Panchama was born on December 6, 1975. This publication would later become the soul of the Dalit movement in Karnataka.

The story of Panchama began in a mixture of frustration and hope. Following a failed attempt to unite various Dalit factions in Mysuru in October 1975, a group of young activists decided to proactively address the situation. On December 6 (the death anniversary of Dr B R Ambedkar), they launched a newspaper named Shoshita, The Exploited. Within a few months, it was renamed Panchama, with an aim to spread the Dalit movement and Ambedkar’s ideas.

In its early days, Panchama was published from Mysuru before relocating to Bengaluru. Indudhara Honnapura served as its founding editor, Devanura Mahadeva as managing editor and H Govindaiah as publisher.

The editorial team included Ramadev Raake, Shivaji Ganeshan and Shivamallu Devanuru. Over the years, the paper saw changes in its editorial leadership, publisher and team, but its spirit remained steadfast.

For the next 15 years (1975–1990), Panchama was more than a newspaper; it was a cultural movement. At a time when several big media houses either ignored Dalits or viewed them with pity, Panchama broke the silence.

It became the perfect platform for Dalits and other marginalised communities to express their pain, anger, experiences of untouchability and creativity without hesitation.

Inspired by Ambedkarite ideology, the paper aimed for total social transformation and the annihilation of caste. It became a fearless chronicler of injustice, documenting atrocities, social boycotts and violence in villages like Kolar’s Hunasikatte and Tumakuru’s Dasanapura, while exposing the negligence of the government.

The paper gave rise to a new Dalit aesthetic, championing the belief that lived experience is the truest source of knowledge.

It provided a political and philosophical framework for literary titans such as Devanura Mahadeva, Dr Siddalingaiah, H Govindaiah, K B Siddaiah, Kotiganahalli Ramaiah and others. Crucially, it connected caste struggles with class issues, standing against capitalism and feudalism and advocating for labourers and poor farmers in the pursuit of a democratic and casteless society.

Devanura Mahadeva recalls a moment of pride: “Kuvempu used to read Panchama. Whenever an issue was delayed due to our financial constraints, he would summon Tejaswi (Kuvempu's son) and ask, ‘Why hasn’t the paper arrived?’ Tejaswi would come to us and say, ‘If Anna (Kuvempu) doesn’t read Panchama, he feels something is missing.’ Tejaswi even helped us financially. The very fact that Kuvempu read our paper was a tremendous honour.”

Despite financial constraints and changes in leadership, Panchama left an indelible mark. Although it eventually ceased publication in 1990, its spirit continues to inspire. Today, its legacy is being revived through plays like Panchama Pada and other cultural activities that rediscover the songs, articles and messages of resistance that were published in the Panchama.

Half a century later, Panchama stands as a powerful testament to the impact a small, committed publication can have in shaping history, altering literature and giving a roaring voice to the voiceless.

(The writer is a Kannada author and journalism faculty)