Distress migration, joblessness, two successive years of Covid-19 lockdowns flattening its tourism-based economy and inflation are the issues that should guide the people in Uttarakhand, when they would queue up and cast votes at the 11,697 polling booths across the state on Monday. But, Uttarakhand differs from the rest of the heartland, in terms of demography and, therefore, politics.

The OBCs, a force in neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, are less than a fifth of Uttarakhand’s electorate. Dalits are 19 per cent and Muslims 13 per cent but concentrated in four of its 13 districts – Udham Singh Nagar, Dehradun, Nainital and Haridwar. Unlike any other state except neighbouring Himachal Pradesh, Thakurs and Brahmins account for at least half of Uttarakhand’s 83 lakh electorate.

In the past, neither Dalit and OBC politics of assertion, nor aggressive Hindutva could overwhelm Uttarakhand’s very own political fault-lines.

The Thakur versus Brahmin rivalry, friction between its two regions of Tehri and Garhwal, and its hills and plains districts have shaped Uttarakhand’s politics in the four assembly polls since being carved out of Uttar Pradesh in November 2000.

The leaders belonging to the two castes switch loyalties seamlessly between the two principal political players – the Bharatiya Janata Party and Congress.

The reins of power have similarly exchanged hands between the two parties and the two sets of leaders.

Uttarakhand’s electorate has never returned an incumbent government in the last four assembly polls. Of its 11 chief ministers, only one completed a five-year term, Narayan Dutt Tiwari, who was in office from 2002 to 2007. Nor has a sitting chief minister won their own seat since 2002 – the BJP’s BC Khanduri lost in 2012 and Harish Rawat of the Congress lost both the seats he contested in 2017.

Would the 2022 Assembly polls buck the trend?

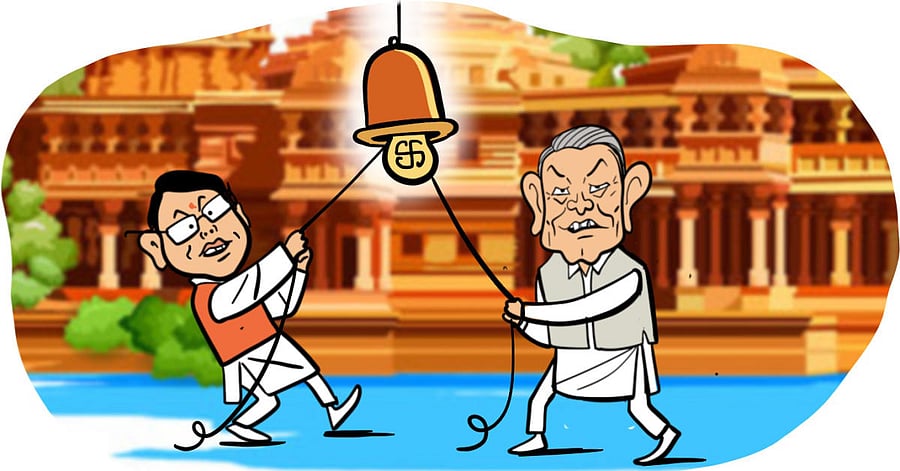

The BJP central leadership has tried to douse the simmering anger of the people by ringing out leadership changes. It sacked two chief ministers last year. Trivendra Singh Rawat was made to resign after four years in office, but his successor Tirath Singh Rawat lasted only 116 days. It eventually settled on Pushkar Singh Dhami. At 46, Dhami is much younger than his Congress rival Harish Rawat (73) and helped BJP reconnect with the state’s youth.

Another notable development is the Hindutva outfits upping the ante. There are calls for legislation to curb alleged ‘love jihad’ and ‘land jihad’. Then there was the ‘Dharm Sansad’ in Haridwar, led by Yati Narsinghanand Saraswati.

The opposition Congress, expected until a few weeks back to defeat the BJP, is struggling with infighting. One of the party’s state unit presidents, Ranjit Rawat, went public that he was upset the party was fielding Harish Rawat from the Ramnagar constituency.

The Congress also fears the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) would eat into anti-incumbency votes to wreck its chances.

Migration as a poll issue

Uttarakhand primarily survives on tourism to its hill stations and pilgrims to its Char Dham – Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath. Two years of Covid-19 lockdowns hurt the tourism sector. It added to the already rampant migration from its villages.

In 2017, the BJP government formed the ‘palayan aayog’, a migration commission. In a report in 2018, it said 734 villages turned ‘bhootiya’ since 2011. There were 1034 ghost villages until 2011. All parties have promised unemployment stipends, job creation and other plans to stop migration. Hindutva outfits, with little evidence, claim “outsiders” are buying land in the hills, termed it ‘land jihad’ and demand a return of stricter land ceiling laws. The 2018 report enumerated declining agriculture and low rural incomes as primary push factors for migration. Poor healthcare and transportation facilities contributed. Migration has national security implications. Hundreds of villages bordering Tibet have either emptied or have only the elderly. According to political observers, migration is not an emotive issue.

Modi factor

Unlike the other states where his appeal has shown diminishing returns in the assembly polls, Prime Minister Narendra Modi remains popular in Uttarakhand. Nationalist fervour drives political choices for many families as the state has strong representation in the defence forces. A state as small as Uttarakhand has two regiments – Garhwal Rifles and Kumaon Regiment – in the Indian Army.

Within days of the Congress launching its campaign focussed on regional aspirations, or “Uttarakhandiyat”, the prime minister wore a ‘Uttarakhandi cap’ at the Republic Day Parade to highlight his bond with the people of the hill state. He has visited the state often during his eight-year tenure, whether to lead the International Yoga Day in 2018 or for pilgrimage to Badrinath and Kedarnath.

Election results since 2014 are evidence that the Modi factor and BJP’s efficient election management has tilted the scales. The BJP has monopolised the vote share of smaller parties and independents.

In 2014, the BJP won all the five Lok Sabha seats from Uttarakhand with a vote share of 34 per cent against the Congress’s 21 per cent. Smaller parties and independents secured a whopping 44 per cent. In the 2017 assembly polls, the Congress increased its votes to 33.5 per cent, but the BJP comprehensively outmatched it with 46.5 per cent, winning 57 of the 70 seats. In 2019, the BJP bagged 61 per cent to 31 per cent for the Congress. In five years, the vote share of others and independents reduced from over 40 per cent to less than 10 per cent.

While the BSP shows a decline, the entry of the AAP could determine the outcome on several seats, particularly the hill seats where the winning margins are thin.