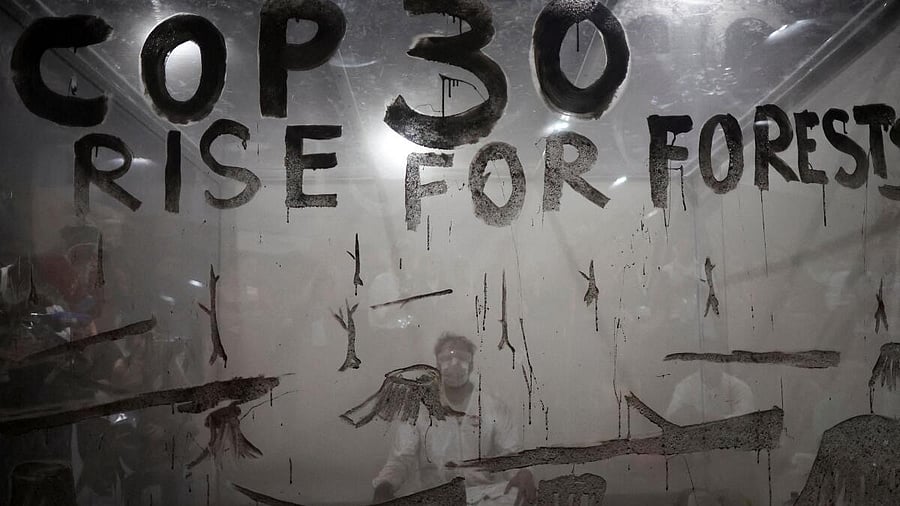

The high drama at COP30 had a disappointingly familiar denouement: an unpromising resolution that once again shied away from oil and gas. Had meaningful action followed COP28’s call to transition away from fossil fuels, Belem would not have been all about them. COPs no longer inspire hope.

The 1992 Earth Summit in Rio De Janeiro laid the foundation for UNFCCC to help stabilise greenhouse gas concentrations before they ballooned into the existential threat they are today. The discussions based on intergenerational justice agreed that developmental goals of one generation should not compromise the ability of future generations to meet theirs. Its humanitarian wisdom should have moderated extractive industries and petrostates. Instead, today’s youth have been let down by the ‘adults’ in policymaking, prompting Greta Thunberg to ask why they should study for a future no one is willing to save.

Trade has long impaired climate negotiations. Ironically, both the UNFCCC and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) came into being in 1994—pursuing parallel paths like estranged twins. Trade agreements became binding; climate commitments remained voluntary and unenforceable. Sustainable development was subordinated to the interests of capitalism, which drove government policy with scant regard for the ecological damage globalised trade leaves behind.

The Stern Review described climate change as the “widest-ranging market failure ever.” A free-market economy driving trade through globalisation has reasons to resist decarbonisation. The fossil fuel industry’s contribution to GDP gives it immense clout. Many other industries run on fossil fuels and resist anything that might undermine profitability. For energy transition to happen, governments must shoulder the initial costs and ensure localisation of resources to generate jobs and regional economic growth. But WTO rules disallow such regulations. This was evident in Ontario, Canada, which was compelled to dismantle its policy provisions protecting local suppliers and labour in its green energy plan—killing what could have been a pioneering model for decentralised energy transition.

The interpenetration of the fossil fuel industry and climate negotiations was stealthy until its stunning appearance in Dubai, where the chief of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company presided over COP28. It became fashionable to showcase renewable subsidiaries of oil giants as a commitment to transition while keeping their core intact. A Brown University report released at COP30 details new obstruction tactics led by the fossil fuel lobby—framing climate risks as distant and exaggerated while overselling unproven technologies. It revealed that 25% of the COP30 participants were aligned with fossil fuel interests.

A distorted view of climate justice has also contributed to the COP impasses. Debated extensively since the Earth Summit, climate justice argues that the onus of reducing emissions cannot be shared equally by those who contributed to it the most and those who suffer the most. It is now interpreted differently: the developed world, having prospered through dirty energy, cannot imperil the developing nations’ progress. Meant originally as a rationale for climate finance, it has been distorted. We are unable to see either the scientific limits of global emissions or the imperative of combining the energy needs of developing countries with the economic incentives of clean energy. The Global South, including India, argues for a continued licence to emit. Petrostates have appropriated this narrative, turning it into an emotive issue around the developmental aspirations of the developing nations. The idea of climate justice as energy transition financed by the developed nations for equity for the rest of the world stands inverted to mean the right of petrostates to expand their fossil fuel ambitions.

If COPs continue to fail, is there a way out? Where governments have made little headway, is there a business case for corporate climate action? It may sound counter-intuitive when fossil fuel giants contribute 75% of emissions (Scope 1). But the remaining 25%—Scope 2 (purchased electricity) and Scope 3 (supply chain and downstream use) emissions—offers hope. These represent major energy demands from other industries, many of which also make up the bulk of the energy demand of the fossil fuel industry but have committed to carbon neutrality by 2050. If they honour this commitment and remain open to public scrutiny, it could be transformative.

It makes business sense. Corporate finances are already hit by heat stress on data centres, rising capital costs, and frequent supply chain disruptions. A World Economic Forum report estimates climate-related losses since 2000 at $3.6 trillion. A climate-secure future is essential for the survival of businesses, besides opening new opportunities through green transition. Consumers, governments, and civil society will all need to ensure corporate accountability in decarbonisation. Having exhausted all our energy on the elusive COP promise, this pathway is worth engaging.

(The writer is an associate professor of practice at the Indian Institute of

Management, Bodh Gaya, and is pursuing research at

St Joseph’s University,

Bengaluru)