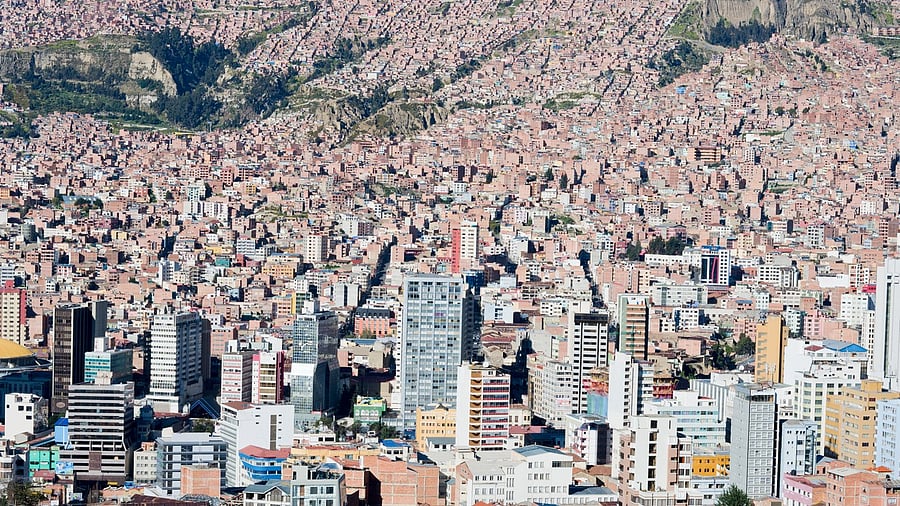

Image showing the city of La Paz in Bolivia. For representational purposes.

Credit: iStock Photo

Population sustainability may soon become a buzzword for countries grappling with the consequences of either a growing or shrinking population, both of which can significantly impact their socio-economic and environmental requirements.

An overemphasis on population control, aimed at reducing the population, has resulted in some countries facing the challenge of sharply declining population growth rates while others continue to struggle with unchecked population growth.

Globally, we have not yet reached the replacement level – the rate at which the number of people born equals the number who die. This replacement rate is typically considered to be 2.1 children per woman, which would allow a population to stabilise over time.

While the global total fertility rate (TFR) has been falling, it remains above the replacement level. According to the United Nations, the world’s population is projected to keep growing for the next 50 to 60 years.

The global TFR has been declining. The UN estimated it at 2.3 in 2022. This means that, on average, more than two children are born per woman globally – still above the replacement rate. However, the global population is projected to peak around 2084, after which fertility rates are expected to decline further, falling to 1.8 by 2100—well below the replacement level.

There is wide variation across countries: some are experiencing rapid population growth, while others face decline. This disparity stems from differing fertility rates, which measure the average number of children born to women of childbearing age in each country.

Both extremes – rapid population growth and sharp declines – can be unsustainable economically, socially, and environmentally. What is needed is sustainable population growth, where the number of births roughly equals the number of deaths, keeping the population at a static position.

To achieve this balance, a country should aim to maintain its fertility rate around the replacement rate of 2.1. While much public discourse focuses on the problems of population growth, population shrinkage can be equally disruptive to the development and economic stability of a country.

According to World Bank data, the global fertility rate has declined from 4.7 in 1950 to 2.3 in 2022 – more than halved in less than a century. The drop is mainly attributed to greater access to contraception, reduced child mortality, and more women becoming educated and prioritising careers over early or large families.

Countries with fertility rates below the replacement rate may soon have

ageing populations and declining population sizes.

While lower fertility rates and the resulting population contraction may be beneficial in densely populated countries struggling to provide basic services, it can lead to a shrinking workforce and fewer young people supporting a growing elderly population. This imbalance strains public finances, particularly in countries where younger generations fund social welfare and pension systems. A reduced labour force can impact economic productivity and innovation.

Some countries still have high fertility rates like Niger (6.6) and Angola (5.7), while others are seeing very low fertility rates like Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea at 1.1 and Hong Kong at 1.2. Several European countries, including the Scandinavian nations like Norway and Sweden, have fertility rates below 1.5.

Interestingly, in response to declining fertility, China scrapped its long-standing one-child policy and now permits couples to have three children. Afghanistan’s fertility rate is still considered high at 4.5, though this marks a substantial reduction from being one of the highest in the world at 8.0 in the 1990s.

In some countries, religious and cultural practices discourage family planning and birth control, leading to higher rates of population growth. In Europe, fertility rates remain below the replacement rate of 2.1. France has the highest rate in the region at 1.9. The government, being forewarned, has started incentivising large families. Even Norway has started making it financially profitable for women to give birth to more children.

India, too, had reached a relatively comfortable position, with its population growth rate at the replacement level of 2.1 a few years ago. However, recent UN data shows that India’s rate has fallen to 1.9, which is cause for concern. This downward trend must be monitored

and addressed immediately.

It is no surprise that one does not hear of “population control” measures once commonly heard earlier anymore. Yet, it is more important than ever that India, which is already the most populous country in the world, takes deliberate steps at this state to stabilise its population.

Despite the fact that India is the most populous country in the world with 146.39 crore people, it must aim to maintain this level. The population should

neither be allowed to grow unchecked nor decline drastically. Population

sustainability, not just control or growth, should be the guiding principle moving forward.

(The writer is a senior journalist)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.