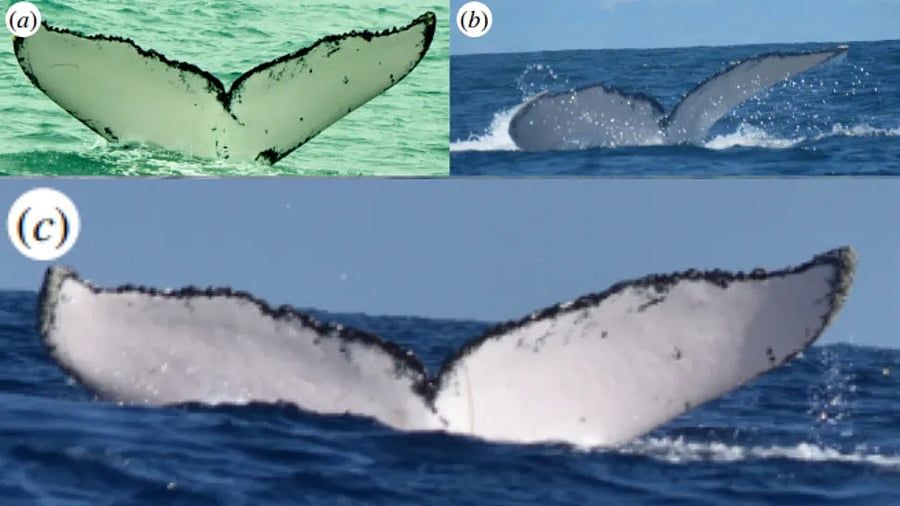

The same humpback whale observed in (a) the Gulf of Tribugá, northern Colombian Pacific, on 10 July 2013, photographed by N. Botero-Acosta of Fundación Macuáticos Colombia; (b) Bahía Solano, northern Colombian Pacific, on 13 August 2017, photographed by E. D. Mesa of Madre Agua Colombia; and (c) Zanzibar channel, off Fumba on 22 August 2022, photographed by E. Kalashnikova.

Credit: © 2024 Kalashnikova et al. R. Soc. Open Sci (CC-BY 4.0))

A male humpback whale journeyed over 13,000 kilometres across 3 oceans, setting a new record for the longest great-circle distance ever recorded for a humpback whale.

According to a report in Live Science, the whale is estimated to have travelled 13,046 kilometres starting from Colombia’s eastern Pacific coast and ending near Zanzibar in the southwest Indian Ocean.

While the whale might have taken a longer path, the shortest distance between the two points, which is known as great-circle distance between two points, was 13,046 km.

The motivation for this journey, while unclear, is believed to have been the search for sex. Climate change and population growth in the area might have also been factors.

The whale likely travelled eastward from Columbia, rode on ocean currents towards the Southern Ocean and potentially visited humpback whale populations in the Atlantic Ocean, the study's co-author Ted Cheeseman told Live Science.

"This was a very exciting find, the kind of discovery where our first response was that there must be some error," said Cheeseman, who is a doctoral student at Southern Cross University in Australia and director of Happywhale, an image database where the researchers collected evidence for the study.

Together with the astounding mileage, one of the most important findings from the study was that the whale dropped in on several humpback whale populations along the way, exploring farther afield than any other humpback whale known to science, Cheeseman told Live Science.

Humpbacks usually travel between feeding areas in polar waters and breeding grounds in the tropics. While their migration trips exceed 8,000 km, they don't tend to travel in the east-west direction and generally don't mix with other populations.

As such, the discovery of this journey by the whale defies the norms its kind are known to follow. Ekaterina Kalashnikova, lead author and biologist with the Tanzania Cetaceans Program told Live Science, "This behaviour sheds new light on their ecology."

The discovery is based on photographs the researchers took between 2013 and 2022, and which they subsequently posted on Happywhale.

The research was published on Tuesday (December 10) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.