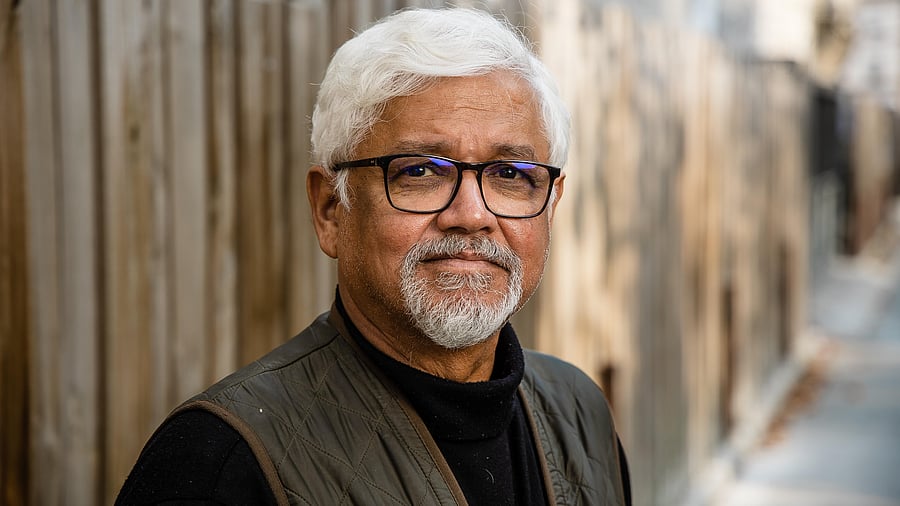

What is our creative response to the most pressing crisis of our times — climate change, habitat loss, and displacement, among other such ecological concerns? It is this question that one of the most important literary figures of our times, Jnanpith Award and Erasmus Prize winner Amitav Ghosh, has consistently addressed, and followed up through his work, most recently, Ghost-Eye, his latest novel.

In The Great Derangement, he asks, “In a substantially altered world, when sea-level rise has swallowed the Sundarbans and made cities such as Kolkata, New York and Bangkok uninhabitable, when readers and museum-goers turn to the art and literature of our time, will they not look, first and most urgently, for trace and portents of the altered world of their inheritance.”

He goes on to add, “And when they fail to find them, what can they do other than to conclude that ours was a time when most forms of art and literature were drawn into the modes of concealment that prevented people from recognising the realities of their plight?” Subsequently, Ghosh wrote Gun Island, Jungle Nama, and now, Ghost-Eye — as if to provide answers to the questions he has asked. In Bengaluru for a book tour of his latest work, he spoke with DHoS at length about all the themes of his latest work.

A revival of familiar themes

In The Ghost-Eye, three-year-old Varsha Gupta suddenly asks for fish in a strictly vegetarian Marwari household, leading to a series of events that take us to the Sundarbans. She remembers food and incidents of her past life, and the reader is led on a journey of many discoveries from there on.

The ‘ghost-eye’ here is a reference to not just the physical condition called heterochromia, where an individual has irises of different colours, but to a different way in which to perceive the world. The book, which unfolds against the backdrop of the pandemic, reprises the characters Tipu, Nilima, Piya and Dinu, among others, and takes us back and forth between New York and Calcutta. Ghosh addresses themes such as myth, memory, food, ecology and identity in The Ghost-Eye. Food is a big motif, particularly fish. “Food is the way in which humans relate to the environment. I mean, food is the most important thing in the world. One of the issues that I would like to foreground is how disrupted our food systems have become,” says Ghosh.

By focusing on food, the author is also drawing our attention to aspects like invasive species and local species.

‘Stranger than we think’

A big theme of Ghost-Eye is also reincarnation, and not merely as a literary device. “I have been interested in the question of reincarnation for a long time because it figures so much in our culture, films, and our history. For example, in Satyajit Ray’s Sonar Kella, the same theme occurs. If you grow up in India, for us, it’s just a fact of life. It’s a way of connecting to the past, and a way of saying that we just don’t exist on the planet, like isolated individuals, that we are preceded by complex connections. That has always interested me. It completely appends our usual material understanding of reality, as it were.” “I just want to suggest that the world is much stranger than we think.” The breathless pace of “incredulous” events demands big leaps of imagination on the reader’s part. But the uncanny is just a way of life in Ghosh’s works, a sort of running theme, starting from The Calcutta Chromosome to The Hungry Tide, Gun Island and now, Ghost-Eye. “I think there are many things in the world that we don’t understand and cannot explain. That doesn’t mean they don’t happen. I think we have all experienced things that are very hard to explain. After all, you can’t expect economists to write about those kinds of things, so who’s going to talk about such things? That’s how stories begin. I wanted to write about something that would be very much grounded in reality, but that’s how strange things happen, isn’t it?” asks Ghosh.

“Strange things”, the presence of the “non-human voices” and the “environmental uncanny” are themes that Ghosh uses to challenge the Western mechanistic way of looking at not just the climate crisis, but our presence on this planet. Even in the 1996 novel, The Calcutta Chromosome, Ghosh presents “counter-science” which operates in silence, secrecy and language-less communication, as opposed to a rules and order-based Western way of thinking.

Policy matters

Talking about the way nations and policymakers look at climate change, Ghosh says, “For a while, governments in Europe and the US made a big show of being interested in climate change and tried to make policy responses. But now, they have even stopped the pretence of doing that.”

What about the Global South, we ask? “We are in an unenviable position. There should be equitable use of energy across the world. I mean, climate change is fundamentally a story of inequality. Without addressing the question of inequality, it really becomes impossible to even think of any kind of progression on this.” Talking of our response to the climate and environmental crisis, one wonders if science has failed us. Should it even be a “versus” situation, we ask Ghosh. “Science is a tool. It depends on political will. I mean, alternative energy systems exist. It’s merely a question of scaling them up. In China, they have successfully done that, whereas in America and the West, they are going in exactly the opposite direction. So it’s not science that has failed us. I would say that it’s the political class that has failed us.”

Is the burden on the individual, then, to cope with the biggest crisis of our times? “How can people cope individually? You and I can’t build an electric grid. That has to be done collectively. The individual just tries to protect themselves and their family, which can often be a counterproductive thing.”

Hope then has to come from the stories, from our ability to remember, reimagine and pay attention to the non-human voices in our midst.

A vitalist politics

In populating his fiction with Bon Bibi — the guardian spirit of the jungle, Dokkhin Rai — the tiger, Manasa Devi — the serpent goddess of the Sundarbans, or the Makara – the sea creature of Hindu mythology, Ghosh stresses his belief in vitalist politics. As he writes in The Nutmeg’s Curse, “It is empathy that makes it possible for humans to understand each other’s stories: this is why storytelling needs to be at the core of a global politics of vitality.”

So, does he see a revival of vitalist politics? “It’s already happening. I think one of the most positive developments is the Rights of Nature movement. I’ve even mentioned that in the book (Ghost-Eye). And the Rights of Nature movement is very much a vitalist politics. Because what they’re actually saying is that a river is a person, that mountains can be sacred. And the moment they say that, what they’re really doing is creating vitalist politics,” explains Ghosh.

Ghost-Eye serves as a shrine to all of Ghosh’s ideas and themes that are part of his earlier works.

Readers of the Ibis trilogy may recall the shrine of Deeti, the opium farmer and indentured labourer, who later turns into a venerable matriarch. In this shrine, she makes etchings on the walls of a cave to keep a record of her journeys. Ghosh seems to have done a Deeti and turned Ghost-Eye into a memory keeper.

Climate writing: Beyond dystopia

The Little Ice Age was a period of severe cooling and lasted between the 13th and late 18th to early 19th centuries. There were periods when London’s River Thames froze, and frost fairs were held. If you were to look at the writing of that time, you’ll find a familiar theme — printers setting up stalls and booths on the river for people visiting the fair. These serve as reminders of a time when a climate change event lasted for centuries, although people of the time didn’t know it as the Little Ice Age. Most of these notes came with a footnote saying: “Printed on the Ice upon the Thames” with the date.

Climate writing in that sense is hardly a new concept — be it in the form of essays, poetry and journalism. However, it is only in recent years that climate literature, and specifically, fiction, has come to be known as a literary genre (cli-fi) and not just part of the larger science fiction genre. Although the term ‘cli-fi’ has come into circulation post mid-2000s, there have been novels addressing climate change, from the 19th-century Jules Verne’s novel, ‘The Purchase of the North Pole’, to the dystopian fiction of author JG Ballard. These were followed up by authors Octavia Butler, Margaret Atwood, Kim Stanley Robinson, Barbara Kingsolver and Richard Powers, who have all written novels in the genre.

A lot of climate writing tends to highlight doomsday scenarios and apocalyptic endings. Does this then lead to climate despair — an overwhelming sense of hopelessness? Possibly. A 2021 study (published in The Lancet Planetary Health) of 10,000 young people (16 to 25 years) across 10 countries showed that 59 per cent were “very or extremely worried” about climate change and over 50 per cent “felt sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless and guilty”.

Climate communication can also be deceptive sometimes, especially on social media platforms. Take greenwashing, for instance, which is a deceptive technique that companies, organisations and individuals use to signal their eco consciousness — and project that they care for the environment more than they actually do. It could lead to the use of vague language, buzzwords and also push concepts and products to consumers who want to be seen as eco-friendly.

This is also an offshoot of the need to be perceived as cool and well-informed about climate change. With climate fiction emerging as a popular genre, the need for writers and publishers to hop onto the bandwagon and play to the gallery (of readers) without an actual commitment could also be a pitfall.

But poetry, parables and fiction can bring hope too. We ask author Amitav Ghosh if literature can indeed serve as motivation for climate action. In an interview, the author observes, “I wouldn’t normally claim that literature can be so motivating. However, in my experience, literally thousands of people tell me that my books have motivated them to take action. Even recently, I was signing books in a bookstore, and so many people came up to me and said, “Oh, you know, after reading your book, I gave up studying engineering and decided to become an activist.”

In her poem, ‘Tell them’, climate change activist and Marshall Islands poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner writes, “tell them we don’t know / of the politics / or the science /but tell them we see / what is in our own backyard.”

Effective climate writing, whether in the form of poetry, fiction or non-fiction, can do what difficult-to-digest data can’t — humanise the experience and create a feeling of empathy.