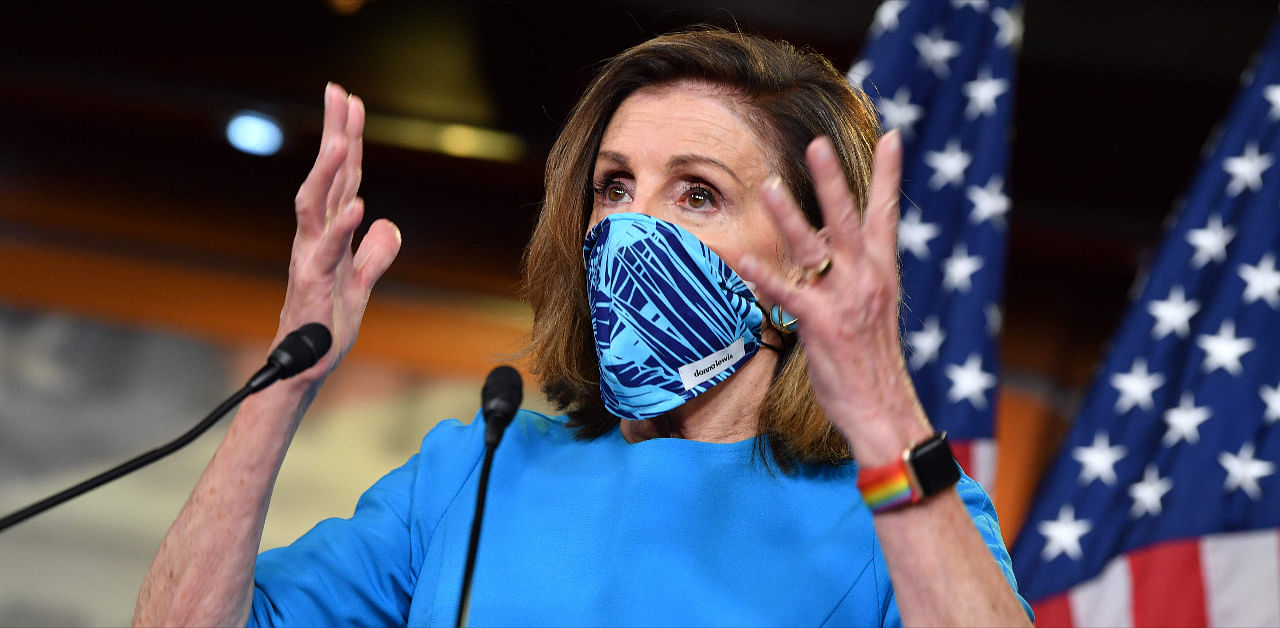

As Democrats’ election losses continue to pile up, Speaker Nancy Pelosi is preparing to lead what may be the slimmest House majority in nearly two decades, with little room to manoeuvre between its feuding progressive and moderate wings as she works to deliver President-elect Joe Biden’s agenda.

Pelosi, who muscled her way back to the speakership two years ago and will be nominated by Democrats again Wednesday, is on track to secure the votes she needs to keep the job come January. Some former opponents are lining up behind her and others packing up their offices after losing.

But her party’s disappointing showing in the elections has left her clinging to the majority by a thread. Democrats’ failure to defeat a single Republican incumbent as they lost at least eight of their own transformed what was a comfortable 232-197 advantage over Republicans into what is likely to be Democrats’ thinnest margin since World War II. With a handful of races still to be called, Democrats are likely to control around 222 seats, effectively allowing no more than a few of their members to defect on any given vote.

Progressives and moderates are already warring over how to use the dynamic to tip the party in their respective directions. For centrist Democrats, that will mean resisting the entreaties of Biden and other party leaders to push through more liberal policies.

“We are trying to figure out who has the guts to hang in there. There will be lots of pressure,” Rep. Kurt Schrader of Oregon, a member of the conservative Blue Dog Coalition, said of talks among moderates about locking arms to block items they consider too progressive. “If Barack Obama calls, are you willing to hang in there? If Nancy Pelosi calls, are you willing to hang in there? If your donors call you, are you willing to hang in there? There are not too damn many.”

Others are pushing to change House rules to deprive Republicans of the ability to force uncomfortable votes that seek to put Democrats on the spot on such issues as socialism, police funding and sanctuary cities. It remains unclear whether Pelosi will bless the changes, but the efforts reflect a recognition that Republicans, energized by their strengthened numbers, are eager to try to drive wedges between Democrats.

Pelosi has remained upbeat, calling the narrow margin of control an “opportunity” for the party, not a setback. And her swift drive to lock up support for another two years as speaker, despite the electoral losses, reflects how, even as they disagree bitterly on how to proceed, the two opposing factions in her party have placed a common trust in her.

“It is smaller now, but we still have the power of the majority,” Pelosi told reporters last week. “But on top of that, our leverage and our power is greatly enhanced by having a Democratic president in the White House, especially Joe Biden in the White House, who is the man.”

Only two Democrats, Jared Golden of Maine and Elissa Slotkin of Michigan, have said that they will not vote to make her speaker. Of the 15 Democrats who opposed Pelosi two years ago, four have lost and one is now a Republican. At least two, Jim Cooper of Tennessee and Jason Crow of Colorado, now say they will support her. Others, like Schrader, appear open to joining them, or voting “present” to lower the total Pelosi needs, with only a few lawmakers outstanding.

Democratic leaders are confident they will still have unified support in their caucus — no matter its size — to pass a series of carefully negotiated, bread-and-butter bills on good governance, prescription drug pricing, universal background checks for gun purchases, voting rights, and new protections for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.

“We did a lot of work in the last Congress to learn about these bills, to socialize them, to talk to our constituents, and we have all taken votes on these bills,” said Rep. Katie Porter of California, an outspoken progressive who just won a second term in a traditionally conservative-leaning Orange County district. “That makes it a lot easier to move these bills in the next Congress.”

That may be true, but most of them were written with little hope of gaining Republican support or becoming law. If Democrats want to make law next year on issues of possible consensus like infrastructure, prescription drug pricing or criminal justice reform, they will need to incorporate input from a Democratic White House with its own preferences and from Republicans whose support in the Senate would be crucial to any legislative accomplishment.

Things could quickly get messy. Complex bills require a careful balance of interests and compromises, and any change threatens to upend it, reigniting fights among Democrats.

And the situation in the Senate, where Democrats will have at best a one-vote majority and a supermajority of 60 votes is required to advance most major legislation, makes things even trickier. But while control of the Senate will not be decided until after a pair of January runoff elections in Georgia, the party’s competing power centres in the House are positioning themselves to wield maximum power whatever the outcome.

The Congressional Progressive Caucus, the group of nearly 100 of the House’s most liberal members, recently adopted rules to try to centralize its operations around a single leader to wield more influence within the Democratic ranks. Although its members reject the comparison to the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus, which banded together when Republicans had the majority to hold hostage major bills, the changes raise the possibility that what had been a relatively amorphous group of like-minded legislators could become a more disciplined voting bloc.

After four years of Trump’s presidency, they have laid out a set of priorities — from aggressive climate action to universal health coverage and a $15 an hour minimum wage — and argue that the legions of progressives, especially young people, who delivered Biden critical margins in battleground states like Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin will sour on the party if it shies away from action.

“We are absolutely going to stay true to delivering results to the people who turned out to the polls and gave us one more shot at convincing them their voice matters and their vote matters,” said Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington, who is expected to lead the group next year. “We stand to lose people for a generation if we don’t deliver.”

Moderates, who caucus in two groups, the center-left New Democrats and the slightly more conservative Blue Dogs, are trying to do the same. Although their numbers have been diminished by the election losses, they hold sway with the speaker because they represent the districts that will make or break the majority.

Schrader, who opposed Pelosi as speaker in 2019, indicated that he might reconsider this time if she took “a strong role” in counteracting the messaging coming from high-profile progressives, like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, to communicate “what Democrats really are for and what they are not for, so it is crystal clear to the voters.”

Republican leaders are watching the machinations gleefully, and working to stir the Democratic pot. They argue that bigger numbers in the House and the threat of a takeover in the midterm elections of 2022 give them considerably more leverage at the negotiating table, after two years in which Democrats largely ignored them.

“They are going to have to have a reckoning internally to decide which way they are going to go,” said Rep. Steve Scalise of Louisiana, the No. 2 Republican, who leaned into the chief line of attack his party used against Democrats in this year’s campaign — the false notion that they are seeking to impose socialism in America. “Are they going to continue embracing a socialist approach that failed or are they finally going to start working with Republicans?”

Moderate Democrats are also hoping the 2022 midterms could provide another powerful incentive for bipartisan compromise. The president’s party tends to lose seats in midterm congressional elections, and with Republicans already recruiting candidates in competitive districts, Democrats who narrowly won reelection this month will be highly motivated to produce legislative accomplishments they can show voters as they fight to hang onto their seats.

“With Joe Biden in the White House, the primary focus and priority should be to get some wins for the American people by signing legislation into law,” said Rep. Stephanie Murphy of Florida. She said that an “exorcism of the emotions” was appropriate after the election losses, but that lawmakers need to move on.

Murphy is among those contemplating changing House rules to try to nip Republican gamesmanship in the bud. She has proposed raising the threshold for the minority to win adoption of their own proposal at the end of a legislative debate, from a majority to two-thirds.

Rep. Ted Lieu of California has proposed eliminating the maneuver altogether, calling it “a gotcha motion designed to allow the minority party to run campaign ads,” altogether.

Deccan Herald is on WhatsApp Channels| Join now for Breaking News & Editor's Picks