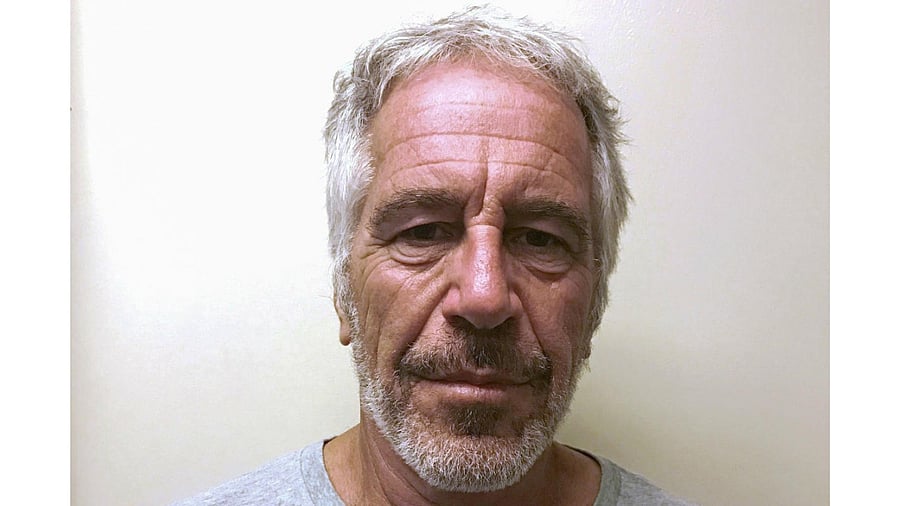

Jeffrey Epstein

Credit: Reuters Photo

Stephanie A. (Sam) Martin For The Conversation

Boise (US): The Jeffrey Epstein story has slipped in and out of the headlines for years, but in a very particular way. Most news articles ask a specific question – which powerful men might be on “the list”?

Headlines focus on unidentified elites and who may be exposed or embarrassed, rather than on the people whose suffering made the case newsworthy in the first place: the girls and young women Epstein abused and trafficked.

Right now, the story is entering a new phase. A federal judge has authorised the Justice Department to unseal grand jury transcripts and other evidence from Epstein companion Ghislaine Maxwell’s sex trafficking case.

A court in Florida has cleared the release of grand jury records from a federal investigation into Epstein himself, all under the new Epstein Files Transparency Act. Passed in November 2025, that law gives the Justice Department 30 days to release nearly all Epstein-related files. The deadline is Dec. 19.

Journalists and the public are watching to see what those documents will reveal beyond names we already know, and whether a long-rumoured client list will finally materialise.

Alongside that, there has been a stream of survivor-centred reporting. Some outlets, including CNN, have regularly featured Epstein survivors and their attorneys reacting to new developments.

Those segments are a reminder that another story is available, one that treats the women at the centre of the case as sources of understanding, not just as evidence of someone else’s fall from grace.

These coexisting storylines reveal a deeper problem. After the #MeToo movement peaked, the public conversation about sexual violence and the news has clearly shifted. More survivors now speak publicly under their own names, and some outlets have adapted.

Yet long-standing conventions about what counts as news – conflict, scandal, elite people and dramatic turns in a case – still shape which aspects of sexual violence make it into headlines and which stay on the margins.

That tension raises a question: In a case where the law largely permits naming victims of sexual violence, and where some survivors are explicitly asking to be seen, why do journalistic practices so often withhold names or treat victims as secondary to the story?

What the law allows – and why newsrooms rarely do it

The US Supreme Court has repeatedly held that the government generally may not punish news organisations for publishing truthful information drawn from public records, even when that information is a rape victim’s name.

When states tried in the 1970s and 1980s to penalise outlets that identified victims using names that had already appeared in court documents or police reports, the court said those punishments violated the First Amendment.

Newsrooms responded by tightening restraint, not loosening it. Under pressure from feminist activists, victim advocates and their own staff, many organisations adopted policies against identifying victims of sexual assault, especially without consent.

Journalism ethics codes now urge reporters to “minimise harm,” be cautious about naming victims of sex crimes, and consider the risk of retraumatisation and stigma.

In other words, US law permits what newsroom ethics codes discourage.

How anonymity became the norm and #MeToo complicated it

For much of the 20th century, rape victims were routinely named in US news coverage – a reflection of unequal gender norms. Victims’ reputations were treated as public property, while men accused of sexual violence were portrayed sympathetically and in detail.

By the 1970s and 1980s, feminist movements drew attention to underreporting and intense stigma. Activists built rape crisis centres and hotlines, documented how rarely sexual assault cases led to prosecution, and argued that if a woman feared seeing her name in the paper, she might never report at all.

Lawmakers passed “rape shield laws” that limited the use of a victim’s sexual history in court. Some states went further by barring publication of victims’ names.

In response to these laws, as well as feminist pressure, most newsrooms by the 1980s moved toward a default rule of not naming victims.

More recently, the #MeToo movement added a turn. Survivors in workplaces, politics and entertainment chose to speak publicly, often under their own names, about serial abuse and institutional cover-ups. Their accounts forced newsrooms to revisit assumptions about whose voices should lead a story.

Yet #MeToo also unfolded within existing journalistic conventions. Investigations tended to focus on high-profile men, spectacular falls from power and moments of reckoning, leaving less space for the quieter, ongoing realities of recovery, legal limbo and community response.

The unintended effects of keeping survivors faceless

There are good reasons for policies against naming victims.

Survivors may face harassment, employment discrimination or danger from abusers if they are identified. For minors, there are additional concerns about long-term digital evidence. In communities where sexual violence carries intense social stigma, anonymity can be a lifeline.

But research on media framing suggests that naming patterns matter. When coverage focuses on the alleged perpetrator as a complex individual – someone with a name, a career and a backstory – while referring to “a victim” or “accusers” in the singular, audiences are more likely to empathise with the suspect and scrutinise the victim’s behaviour.

In high-profile cases like Epstein’s, that dynamic intensifies. The powerful men connected to him are named, dissected and speculated about. The survivors, unless they work hard to step forward, remain a blurred mass in the background.

Anonymity meant to protect actually flattens their experience. Different stories of grooming, coercion and survival get reduced to a single faceless category.

A window into what we think is ‘news’

That flattening is part of what makes the current moment in the Epstein story so revealing. The suspense is less about whether more victims will be heard and more about what being named will do to influential men. It becomes a story about whose names count as news.

Carefully anonymising survivors while breathlessly chasing a client list of powerful men unintentionally sends a message about who matters most.

The Epstein scandal, in that framing, is not primarily about what was done to girls and young women over many years, but about who among the elite might be embarrassed, implicated or exposed.

A more survivor-centred journalistic approach would start from a different set of questions, including wondering which survivors have chosen to speak on the record and why, and how news outlets can protect anonymity, when it is asked for, but still convey a victim’s individuality.

Those questions are not only about ethics. They are about news judgment. They ask editors and reporters to consider whether the most important part of a story like Epstein’s is the next famous name to drop or the ongoing lives of the people whose abuse made that name newsworthy at all.

The author is Frank and Bethine Church Endowed Chair of Public Affairs, Boise State University