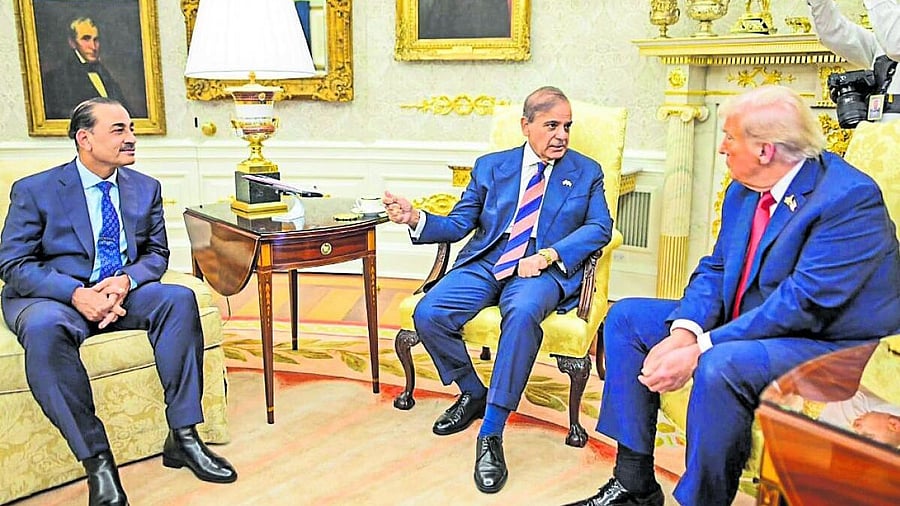

Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif (centre) introduces Field Marshal Asim Munir (left) to US President Donald Trump at the White House in Washington, DC.

Credit: PTI File Photo

There is understandable consternation among sections of Pakistan’s intelligentsia and legal fraternity over the manner in which the 27th Constitutional Amendment has accelerated the slide towards authoritarianism. Apart from further emasculating an already defanged judiciary through the establishment of a Constitutional Court of handpicked judges, it also ventures dangerously into Article 243 to define new powers for President Trump’s much-lauded Field Marshal, General Asim Munir.

Key changes in Article 243 specify that the Army Chief will henceforth be recognised as the Chief of Defence Forces (CDF), positioned at the helm of Pakistan’s armed services. The ‘rationale’ offered for the amendment is that modern warfare has changed drastically, requiring greater integration, synergy, joint planning, inter-service cooperation, and strategic alignment between conventional, cyber and nuclear commands. Lifetime immunity is also granted to all five-star ranks, including those promoted from the Air Force and the Navy.

The office of the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC)—designed to ensure coordination among the Army, Navy and Air Force, and serving as the symbolic head of the armed services for over four decades — will be abolished once the incumbent, General Sahir Shamshad Mirza, retires on 27 November 2025. The position was rotational until 1997, after which the Army reserved the four-star slot for itself. Although technically positioned at the apex of Pakistan’s nuclear command and control, the CJCSC’s role remained largely ceremonial in practice.

Mirza enjoys high respect among his peer group of Generals. As the seniormost officer of the 76th Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) Kakul Long Course, he has had an exceptional career —serving as Director General Military Operations (DGMO) before promotion to three-star rank, later becoming Chief of General Staff (CGS), and subsequently Corps Commander, X Corps, Rawalpindi under General Bajwa. He was one of the main contenders for the top post over an ostensibly senior Officers Training School (OTS) entrant, Asim Munir, in November 2022.

While there was no open confrontation between Munir and Mirza, relations remained frosty. During the tumultuous days of May 2023, rumours circulated that Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) leader and former Prime Minister Imran Khan had encouraged Mirza to overthrow Munir while the latter was abroad. Mirza did not oblige.

Under the amendment, a Commander of National Strategic Command (CNSC) will be appointed, though it remains unclear whether this will be a four-star position. Other questions also remain unanswered: what will be the future role of existing three-star functionaries such as the Director General, Joint Staff or the Director General, Operations at the CJCSC headquarters in Chaklala? Where will the newly announced Army Strategic Rocket Force (ASRF) fit in? Will the Strategic Plans Division (SPD) undergo restructuring?

Munir is keeping his cards close to his chest regarding this reorganisation. He must weigh the discontent of senior Generals of the 80th PMA, who now face a career dead-end. Lieutenant General Asim Malik, currently Director General Inter-Services Intelligence (DG ISI), is considered very close to him. However, the October 2025 notification retaining him as DG ISI and as National Security Adviser suggests he has effectively retired after a four-year term. Extensions are rarely popular among peers, and a promotion to a four-star slot now appears unlikely.

Interestingly, the Islamabad Post carried a post on X (9 November) alleging that “internal rifts” within the Army had reached “a critical point”, turning the changes from “administrative reform” into “a contest of influence, power and strategic anxiety”.

Meanwhile, the court-martial of another former rival, Lieutenant General Faiz Hameed, has concluded. Reports suggest a harsh verdict may be forthcoming, but Munir will need to assess the simmering resentment within the ranks before making the decision public.

Though Air Chief Babar Sidhu may also receive a five-year extension, junior officers of the Air Force and Navy are disgruntled. They traditionally resist enforced jointness and view the amendment as yet another ploy by the Army to centralise control.

Implications for India

India has dealt with military rulers in Pakistan before. Even as they consolidated power domestically, they often attempted to evolve as statesmen, taking steps to moderate the tense political climate between the two adversarial neighbours. This occurred after President Zia-ul-Haq’s cricket diplomacy in February 1987. Despite the ignominy of being the architect of Kargil, General Pervez Musharraf undertook a diplomatic visit to Agra in 2001 (albeit unsuccessfully). Later, during India’s 2006 cricket tour of Pakistan, he famously complimented M S Dhoni’s long hair. His “four-point formula” on Kashmir gained significant traction during the Track II discussions between Tariq Aziz and Satinder Lambah (2005–2007).

Munir’s case appears different. He has had to carefully position loyal Generals following the May 2023 disturbances instigated by the PTI. Throughout his three years as Army Chief, he has had to look over his shoulder constantly — both inside the institution and outside — to counter Imran Khan’s enduring popularity. This insecurity persists despite his extension, granted through amendments to the Army Act, 1952, potentially allowing him to remain in office until 2030.

The Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) government, led by the compliant Shahbaz Sharif, has readily fallen in line, lacking legitimacy after the February 2024 elections.

Munir’s recent speeches — at the Overseas Pakistani Convention in Islamabad (April 2025), and before Pakistani diaspora gatherings in Florida, US, and Brussels (August 2025) —revealed a narrowly India-centric worldview typical of many younger Army officers. He threatened nuclear devastation against India. Addressing PMA cadets at Kakul (October 2025), he asserted that “there is no scope for war in a nuclearised environment”, yet simultaneously warned of “a decisive, beyond-proportions response”.

In this backdrop, India cannot afford complacency and must focus relentlessly on expeditious force modernisation while plugging operational gaps wherever urgently required.

(The writer retired as Special Secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India.)