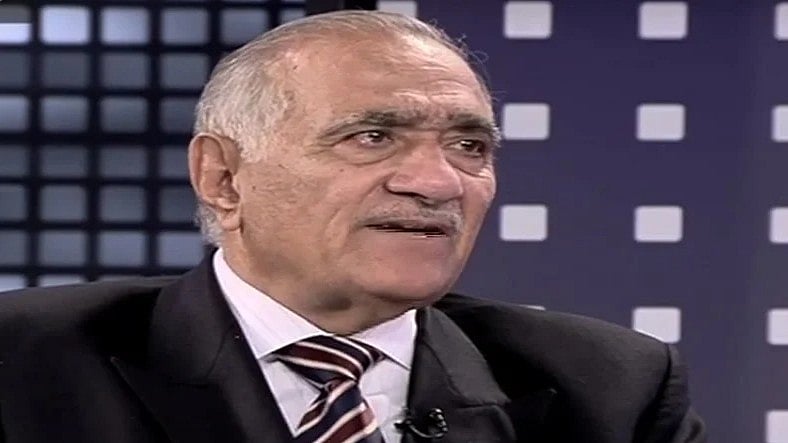

Journalist Bharat Bhushan in conversation with Major-General (Retd.) Mahmud Ali Durrani, Former National Security Advisor, Pakistan.

Credit: YouTube/@RSTV

Former Pakistan National Security Advisor Major General (Retd) Mahmud Ali Durrani, a lifelong advocate of India-Pakistan friendship, passed away peacefully on October 24 in Rawalpindi after a heart attack.

When I first visited Pakistan in 1999, General Mahmud Durrani (not to be confused with the former ISI Chief, Lt Gen Asad Durrani) came to pick me up for dinner from my hotel, along with his wife, Fatima. When I got into the car, he told Fatima, “Look at him carefully. He neither has horns nor a tail. Indians are humans just like us.”

Most Pakistanis, he said to the chagrin of his wife, have a convoluted view of Indians, and he wanted to begin with correcting stereotypes at home first.

For someone who claimed that once he knew Indians as only as figures at the end of his rifle’s sight, Durrani had come a long way. He became one of the most influential establishment voices in Pakistan, arguing for peace with India, and was dubbed ‘General Shanti’ for his efforts.

To convince the sceptics, he wrote a book called India and Pakistan: The Cost of Conflict and the Benefits of Peace, which was published by Oxford University Press, Pakistan.

He kept up his Indian friendships till the end. It may surprise many that Ajit Doval, India’s National Security Adviser, was one of his friends. The two got along famously even before either of them became NSAs. Whenever we talked on the phone, Durrani would ask, “How is my friend the Thanedar?” I would politely tell him that I had no access to him as the NSA.

Durrani, had a distinguished career in the army, becoming General Zia ul Haq’s military secretary and Pakistan’s military attaché in Washington DC. Later, he was to serve as Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States.

He was subsequently appointed NSA by Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gillani at the behest of President Asif Ali Zardari.

Zardari’s wife, Benazir Bhutto, had made a promise to appoint him as NSA if she were elected as the PM. She had met Durrani over dinner as she was preparing to end her exile and return to participate in the elections of 2008. She returned to Pakistan in October 2007 but was assassinated on December 27. Zardari became co-chair of the Pakistan Peoples’ Party with their son, Bilawal Bhutto, and later, the President of Pakistan in September 2008.

Durrani was removed as NSA by Gillani for publicly identifying Ajmal Amir Kasab, the lone surviving terrorist of the Mumbai 26/11 attack, as a Pakistani national. He claimed that Durrani had not consulted him first, while the general said he had consulted Zardari.

Durrani had been working towards India-Pakistan rapprochement much before he became NSA. That is how I first met him — at an India-Pakistan Track-II dialogue organised by Shirin Tahir Kheli, a US diplomat of Indian-Pakistani origin, at the Rockefeller Conference Centre, Bellagio, in Italy. That was in May 1998. That dialogue was bombed mid-way by the A B Vajpayee government’s nuclear tests of May 11, forcing the Indian and Pakistani participants into their own silos once again — Indians gloating; the Pakistanis grim and sullen.

Among the people who were regular participants from Pakistan were Shahryar Khan (former foreign secretary), Syed Babar Ali (businessman and founder of Lahore University of Management Sciences – LUMS), Shahid Khaqan Abbasi (who became prime minister of Pakistan), Makhdoom Shah Mahmood Qureshi (later, appointed foreign minister, twice) and Durrani, while he was still a serving officer.

Even after he retired, Durrani had direct access to General Pervez Musharraf both when he was the chief of army staff and when he designated himself the chief executive of Pakistan. Durrani did not always agree with Musharaff.

When I was on a reporting assignment to Pakistan in July 1999 after the Kargil War, I met up with him. One evening, Durrani told me that after learning about the Kargil incursions, he had visited Musharraf and warned him that it would be a costly misadventure. Nevertheless, Musharraf tasked him to do a policy paper on short- and medium-term threats to Pakistan’s security and installed him in the GHQ.

Shirin and Durrani became the moving force behind the Track-II dialogue, which had the blessing of the prime ministers of both countries. Durrani became a regular visitor to India. It had become a ritual that when he came to India, Vice Admiral (Retd) K K Nayyar would hold a drinks reception (Durrani was a teetotaller) for him at his residence.

It was always a select gathering of Indian policy makers and policy influencers, including Brajesh Mishra, M K Rasgotra, Ambassador Satish Chandra, as well as several others. They would sit around a table and hold friendly but frank discussions about the irritants in the India-Pakistan relations.

Once, I asked him why Pakistan did not stop terrorism against India, the biggest roadblock in the peace process. He replied quite candidly that some in the Pakistani establishment believed that if the terrorism tap was closed, India would never talk about Kashmir. Then he said something which left me stunned, “You see, even if orders are given to close the tap, some amount of terrorism may continue. Those on the lower rungs of the army have worked together with these chaps, gone on operations with them, and developed friendships. It is very difficult to cut off those relationships. So, stopping terrorism will be a very long process.”

Some in Pakistan have linked Durrani to the plane crash that killed Zia ul Haq. Durrani, then the 1st Armoured Division Commander at Multan, apparently persuaded (which he denied) Zia to witness the US M1 Abrams tank demonstration which he was conducting at Bahawalpur. The plane mysteriously crashed after leaving Bahawalpur, killing Zia along with 29 others. An explosive device was apparently planted in a case of mangoes gifted to Zia, which was loaded on the aircraft.

I once asked him what he had to say about such allegations. “Khuda ki khair karo (Be afraid of God). Why would I want to harm the man who was my principal benefactor?” he snapped.

The former chairman of the Pakistan Human Rights Commission, late I A Rahman, on a visit to India once asked me with a mischievous smile, “You have a brother in the Pakistan Army?” When I looked bewildered, he explained, “I was sitting at an event next to a retired Pakistani general and when somehow your name came up in our discussion, I asked him whether he knew you. He replied, ‘Know him? He is my younger brother!’” That was General Mahmud Ali Durrani.

Travel well brother. Your efforts have laid the foundation for a peace that will surely come someday.

Bharat Bhushan is a New Delhi-based journalist. X: @Bharatitis

(Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.)