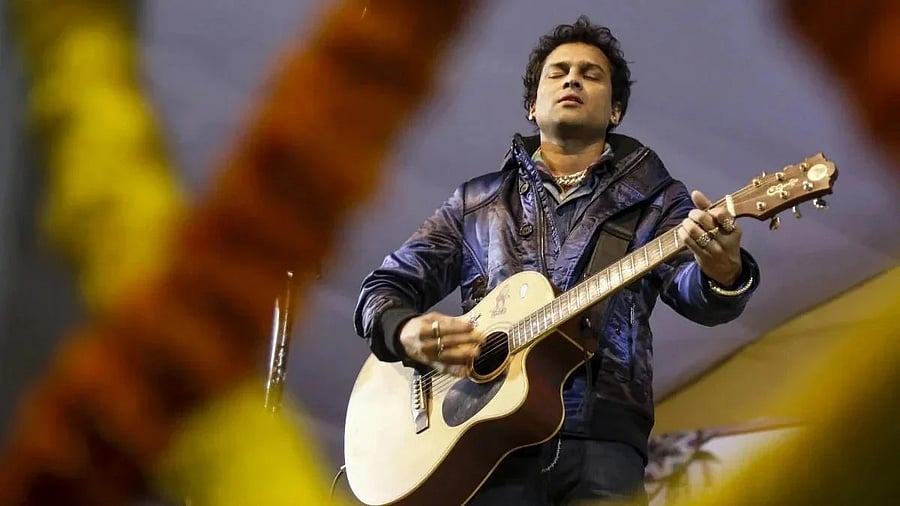

Zubeen Garg

Credit: PTI File Photo

Hours after the news of his death reached Guwahati on September 19, fans of Zubeen Garg started gathering in colleges, street corners and outside his home and spontaneously started singing Mayabini — a song he held close to his heart. This unrehearsed outpouring was a precursor to what the world would witness two days later.

As his body was brought back to Guwahati from Singapore, over 15 lakh people trooped from the airport to his home and then to a stadium where the mortal remains were kept for people to pay their final respects. Thousands had been at the airport from the night before. His hearse took six hours to cross 30 km.

All of this might seem bereft of logic. But then, the love Assam had for the cultural giant betrayed logic, too. Zubeen’s fandom spanned ages — there’s a video of a two-year-old singing his songs in tears, and another of an octogenarian breaking down in a street — and his music transcended genres.

To make sense of this phenomenon, one has to look back at his life and his work.

In 1992, when Zubeen broke into the scene with an album called Anamika, Assam was plagued by insurgency. Bombs and bandhs were part of the lexicon, and while the rest of the country was beginning to taste the fruits of post-liberalisation, many of us were finishing homeworks in the dim glow of kerosene lanterns. Suffice to say that Zubeen came in like a breath of fresh air.

Two years later, after he released an album called Maya, cassettes flew off the shelves, and Zubeen had cemented his position as a force to reckon with. The riffs and the synth were cooler than what Hindi music was giving us at that time. For some of us who scrunched our noses at Assamese music in contempt, Zubeen simply spelt cool.

In the next decade, Zubeen produced the kind of music that people still play today. His vocal dexterity was possibly second to his lyrics. Assam alone has over 30 communities coexisting, and Zubeen has possibly sung in almost all their languages. He’s sung songs in Kannada, in Kokborok, and even in languages like Galo and Adi.

India, however, knows him mostly by Ya Ali — the hit from the 2006 Bollywood film Gangster. It is reductive to distil the musical identity of a man who has sung 38,000 songs in 40 languages to one Hindi hit, but strange are the ways how national identity plays out.

But then, does just musical virtuosity get you a demigod status where every second person in a household can croon like a dream? The answer is no.

A key line from Mayabini, which is now an anthem sung by millions in his memory, goes Dhumuhar xotey mur … bohu jugore naasun (My waltz with these storms has played out across eternities). This encapsulates who Zubeen was for a generation used to venerating Bhupen Hazarika, another cultural giant who, in his time, had brought home his own set of revolutions.

Zubeen was the enfant terrible of the Assamese cultural landscape. He locked horns with the Axom Sahitya Sabha, the custodian of the Assamese culture, on many an occasion. Some saw in him an anarchist, but for many more, he was a revolutionary.

On stage, during one of his iconic Bihu programmes, when he was asked not to sing in Hindi, Zubeen thundered that he was free to sing his own songs and walked away. The diktat had come from the ULFA. In the same breath, when last year, Assam was declared a classical language, Zubeen shot back, “Who the hell is the Indian government to give us anything? We gave you oil, rhino and Zubeen, what have you given us?”

He wore his identity on his sleeve — an identity that was bereft of definition. “Mur kunu jaati naai, mur kunu dhormo naai, moi kunu bhagwan’ok namanu (I do not ascribe to any caste or religion, and I do not follow any god),” he would say.

Born in a Brahmin family, Zubeen had publicly given up the thread that defines his caste. In a state seeped in idolatry, Zubeen once urged people not to allow animal sacrifice in a programme held steps away from the Kamakhya temple. For years, he would define himself as an “atheist” and a “socialist” onstage. That has no parallels in the mainstream Indian imagination.

Only Zubeen would dare to do so. He would criticise Ministers and governments, and lately had taken on the BJP after the opposition to the Citizenship Amendment Act turned into a movement of sorts in Guwahati, turning up at the protest site to lend the heft of his support without anyone asking. He scolded a Minister on TV and sang a song that compared politicians to garbage. But will you witness any hate from politicians? No. In fact, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has only love and admiration to express for Zubeen.

He was also known for his generosity. A Guwahati resident running a prominent NGO informed people on Facebook how Zubeen once rescued a minor househelp who was facing sexual assault from her employer. Several have recounted how his home, heart and wallet were always open for the needy.

For those who have seen Zubeen make the trudge from JB College in Jorhat to Bihu stages and recording studios in Guwahati, a rainy winter evening spells a definitive memory. A river festival was to be held in Guwahati, and Zubeen was to headline it. But before the day came, his sister met with a fatal accident. Fans were devastated, and everyone assumed he would not perform. And yet, he did. As it drizzled in the January evening beside the Brahmaputra, Zubeen sang his heart out.

Widespread appeal

While his appeal spanned from the millennials to college-going students, one will find senior citizens, housewives and even Gen Z children thronging the streets to make sense of his passing and to sing his songs as a tribute.

As his mortal remains were consigned to flames on Tuesday, some of us are mourning the loss of a childhood, while some others are weeping at the end of a musical era, while some others are lamenting the death of a rebel with a golden heart.

Travel well, Zubeen da, there will be no one like you.