The grand Sanjeevani leap translators take

What classics? Those heavy tomes written by dead, male, privileged authors? But who reads them anyway?

The classics question is persistent, as it should be. Several heavyweights — Eliot, Kermode, Italo Calvino, Coetzee, Emily Wilson, to name a few — have all seriously engaged with it to throw much light on the making of a classic. But the one that rings most true in my experience, comes from that quirky genius Mark Twain: “A classic is something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.”

Why is that so? Because, more often than not, classics appear like UFOs from an alien land. They are a hard nut to crack. Given the near total disconnect between our pre-modern past and globalised present, we no longer possess the acumen needed to make sense of our classics. And the tribe of adept, erudite pundits who cared to engage with classical texts is fast depleting.

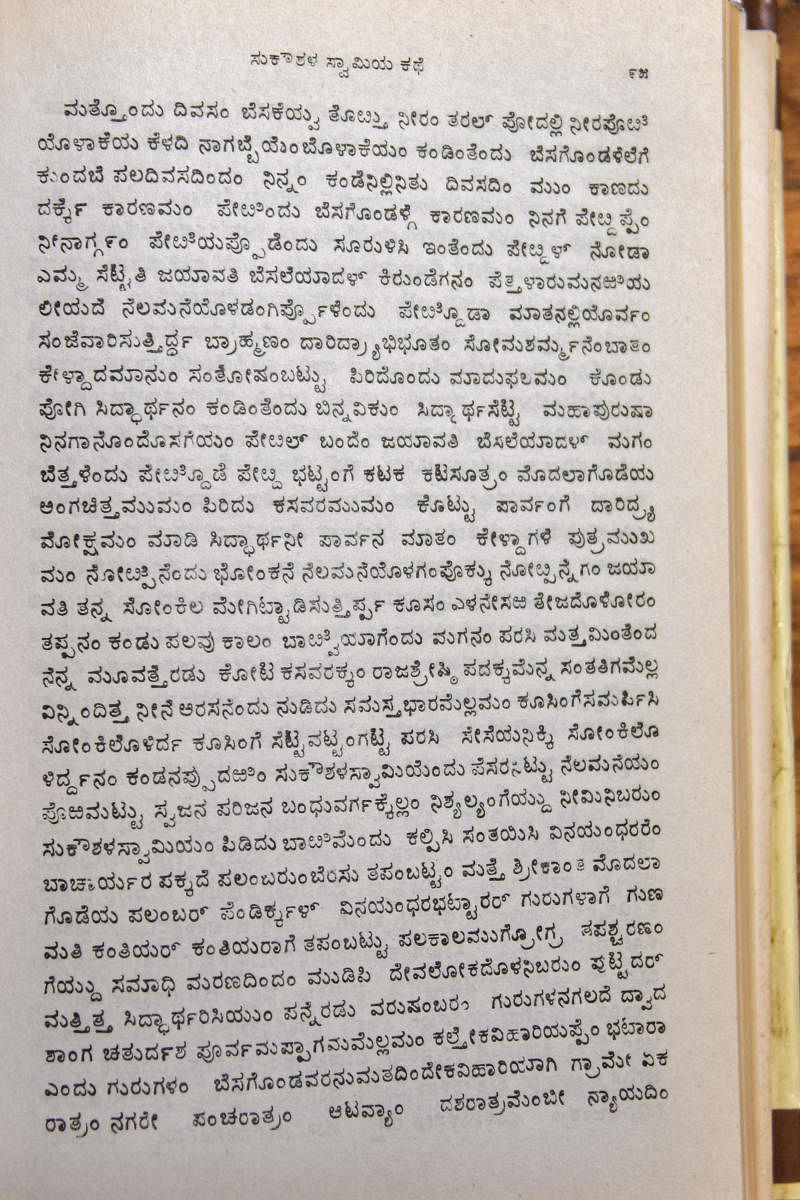

I am not talking only of classics by Greek pioneers like Homer and Iliad, or Russian masters like Tolstoy or Sholokhov, or Sanskrit seers like Valmiki and Vyasa. This challenge is as true about reading our own Kannada writers — Pampa and Ranna, Harihara and Raghavanka, or Kumaravyasa and Lakshmisha. Just look at this page from a 10th century Kannada classic ‘Vaddaradhane’ (below): Tell me where it begins and where it ends. Where are the commas and full stops?

_0.jpg)

This is the least challenging. More is in store. Our kavyas (poetic works) are full of allusions to stories from epics and puranas, 64 domains of knowledge, and descriptions of 18 themes; they are replete with pulverising puns, trying proverbs, mind-boggling allusions, terrorising alliterations, frustrating dviruktis or repetitive phrases, two-timing words, and intractable onomatopoeic words. Welcome to the wilderness. Your compass in this unknown, unknowable jungle are translators.

Thanks to the creativity and labour of translators, classics have an ‘afterlife’, as Walter Benjamin, the Marxist thinker, famously said. Translators are essential for classics to thrive not only across languages, but also within the same language, given the distance in time, space, literary conventions, and sensibility. So how do translators crack these classics?

By translating themselves, by translating the text, and equally, by translating the reader!

Translators are like Hanuman

The process of translation ranges from being difficult to being impossible, with the translation of classics located in the zone of the impossible. Carrying an intimidating, desi text to a sceptical, ‘alien’ reader across the rough seas of difference is a balancing act. The translator has to hold in fine balance contrary claims of fidelity to the original and aesthetic appeal to the reader. So, what is translated is not just the text but the whole context of its production — linguistic, literary, political, religious.

Translators are much like Hanuman who brings the sanjīvani herb along with the entire mountain. They need to equip themselves with a repertoire of skills, strategies, and resources that can open the doors to this inaccessible treasure house of knowledge, experience and expression. For, there are several crucial choices to be made at every stage which presume a scholarly base. Hence, a translator, who is as baffled by classics to begin with, has to translate herself into a scholar-translator who can help lay readers become proficient at reading classics: “Translator, thou art translated!”

The first crucial decision is to choose a worthy text, which requires an intimate knowledge of the terrain of the source literature; a keen judgement of its cultural importance, aesthetic value, and power of the storyline; a measure of its communicability, and an astute gauge of reader expectations. All this has to also speak to her subjective self, as the act of translating is essentially subjective and intuitive.

For instance, I chose Raghavanka’s 1225 text ‘Harishchandra Charitra’ because karuna rasa/compassion is the dominant mood of the text, while most other classical texts are war narratives celebrating male prowess with vīra rasa as their dominant emotion. Compassion seemed to me like a more needed value in these times of daily wars. The larger social purpose that inspired the work inspired me as well. Also, I had fallen in love with the sound of Raghavanka’s poetry even before reading him fully: I had learnt some verses in the Gamaka (art of rendering poetry using ragas from Karnatak music to enhance its emotional appeal) classes in my days of youthful indiscretion had stayed with me after decades! The translated work ‘The Life of Harishchandra’ (Harvard University Press) came out in 2017.

Unlike modern Indian literature, there isn’t a single, fixed ‘original’ text in the case of ancient classics; they come in many editions. And you have to choose the edition that suits you best. For instance, for a forthcoming book for Harvard University Press, I selected the 1970 edition of D L Narasimhachar’s text of ‘Vaddaradhane’ (originally written in 920) as it is considered an authoritative edition by Kannada scholars; and for its extensive introduction, glossary, and text-critical comments which has made for a more confident understanding of the text.

The term translation covers a diverse range of writing practices. The translation could retell in modern prose the story line in summary form; it could abridge a text; it could offer a ‘Shakespeare made easy’ kind of simplification format; it could select or omit sections of the text. For instance, Chapter 4 of ‘Harishchandra Charitra’ which offers a fascinating account of the pulsating life in a brothel, considered inessential and vulgar, has been censored in most Kannada prose translations of Harishchandra. As classical texts are not only literary pieces, but equally knowledge texts, I decided to translate the text in its entirety.

If you have chosen a kavya text, does one translate it as poetry, or as prose, or as a mixture of both? Since premodern, metrical composition does not work well as verse in English, the guidelines from my publishers recommend a translation into contemporary prose. So, the first draft of 'The Life of Harishchandra' was done entirely in prose. As I read the draft again, the intense poetry of the original verses haunted me. I tried rewriting just the first few incantatory chants in verse and it was appreciated by the editors. I re-translated hundred odd stanzas into verse to highlight their unique narrativity, intense lyricism and intricate patterning. I carried out a similar exercise with the dramatic pieces. This highly theatrical text is full of witty conversation and sharp repartee. The drama of the narrative was best told in taut, dramatic dialogues. My attempt was to recreate the narrative poetry of Raghavanka with all its versatility and virtuosity, vitality, values, and voice, using three important modes — verse, prose, and dialogue. The poetry of the text sought its own medium; one can only take credit for humbly listening to the demands of an articulate text.

Choice of strategies

Situated in a post-colonial relationship with English, it is important to resist the predatory moves of that hegemonic language. So, my attempt has been to bend English to make it a fit vehicle for the expressive intent of each of the 728 ṣaṭpadis in the Kannada text. More visibly, I have retained many Kannada or Prakrit or Sanskrit words in the English translation for various purposes: to celebrate local colour, to translate puns, to quicken emotive response, to avoid the risk of naming in English what does not have adequate equivalents that can capture the cultural nuances of words such as holati, holeya, canḍāla, or anāmika, and to point to the various aspects of word play in the text. Also, the structure and style, the sound and sense of each of the stanzas, has been determined by my sense of the Kannada original.

For instance, consider this ṣaṭpadi. The soft, repetitive use of Sanskrit words in this verse gives it a chant-like quality that describes the serene ambience of the forest. But the well-known scholar Prof T V Venkatachala Shastri pointed out to me, in addition, that each of the words śiva, śikhi, śuka, hari, madhu, and bāņa has several meanings. Hence, I had to pick out only those meanings that simultaneously related to the forest, yet being as different from one another to reflect the diversity of the forest. This was my attempt to offer the sense of the verse along with the sound.

“The forest was soaked in a special ambience:

śivamayam, śivamayam, śivamayam: suffused with water, grass, and banyan tree;

śikhimayam, śikhimayam, śikhimayam: replete with peacocks, fires, and venomous snakes;

śukamayam, śukamayam, śukamayam: full of parakeets, mango trees, and sirīśa trees;

harimayam, harimayam, harimayam: filled with monkeys, cuckoos, frogs cascading downhill;

madhumayam, madhumayam, madhumayam: enveloped by honey, spring, and aśoka trees;

bāņamayam, bāņamayam, bāņamayam: engulfed with wooden poles, sounds, and lightning.”

('The Life of Harishchandra'. C5: V 18)

Pre-modern writing practices make abundant use of proverbs. Should we translate proverbs literally or should we find an equivalent proverb in English? Since proverbs refuse to travel easily from their local, folk habitat, I decided to keep them literal as in this example:

“When poet Raghavanka of Hampi describes the beauty of the inner grove,

it proves the saying right: “Kavi, the poet, sees what Ravi, the sun, cannot.” (C 3: V 35)

Our kavya texts, because of their genesis in orality, is often an intensely auditory experience. Consider the following verse: how do we translate onomatopoeic sounds into English? When dogs can bark differently in French and English, why can’t forest fires sizzle differently in different forests? I decided not to translate the sounds.

bhugibhugil bhugibhugil … chiļichiļil chițichițil…

dhagadhagil dhagadhagil… gharigharil gharigharil…

dhagadhagam dhagadhagam dhagadhagil…

chimichimil churuchuril chațachața…

dhamdhaga dhagadhagam… ghuļughuļu….

The fire swelled… splintering… springing like a creeper…,

its blazing flame turning everything black… spewing black smoke…,

red sparks flying in all directions…,

the fire engulfed the forest on all four sides. (C 10: V 6)

Sometimes, as a translator, you make off-beat choices. A terrified hunter chased by a wild boar is stopped by a passerby in the hunting scene in ‘Harishchandra’. As I couldn’t bring myself to make the quaking man speak in English in this condition, I translated it by keeping the original words for tiger and boar.

Running for his life screaming,

hair flying in all directions…

bruised knees with fresh cuts and gashes;

breathless, nostrils dilating-- the hunter.

When a passer-by stopped him to ask,

all he could say was:

“No, no, not hu...hu…huli, not…tiger,

but ha…ha…handi, boar,

right behind…chasing…” (C 6: V 17)

Classics can relax you and slow your pace like yoga, and make you experience with attention the myriad details that make up life; they can make you experience an emotion with full focus like Kudiyattam, that divine art of elaboration, does. Look at this description of the most desirable flower for worship, defined by saying what it is not:

For the king’s worship, the young women gathered the choicest flowers:

flowers not quite green, not quite white, not quite red;

flowers not quite open, their petals not quite visible;

flowers with their inner body intact, their outer petals

not too unfolded, the inner petals not too shut;

flowers untouched by sunlight and untrodden by bees,

unshaken by wind and unbitten by frost;

flowers not single nor entangled with other flowers. (C 3: V 55)

Idlis, puris, kadubu, payasa

While classics are often status quoist, patriarchal, and feudal in their thrust, they can also offer unexpected delights. For instance, in one of the stories in 'Vaddaradhane', a sombre moral tale written a good thousand years ago, Nandimitra, a renunciate is offered a festive meal with idli, puri, kadubu, modaka, and payasa! Later, this ascetic takes up the vow of voluntary death, dies, attains moksha, and goes to heaven. While his soul reaches heaven, his body is being taken out in a grand procession for cremation. Watching it from above, Nandimitra cannot resist the temptation. He descends to earth and joins the troupe dancing before his own hearse! In yet another story, the king, in love with his own daughter, manages to marry her by getting consent from his ministers and the queen after tricking them. If you want to know what the ten stages of erotic love are, read verse 43, in Chapter 4 of 'Harishchandra'.

Translating the reader

But do we know who the readers of our translations of Kannada classics into English are? A handful of scholars and lay readers from the West; and a few more from outside the state. But I would like to submit that, largely, they are the English-educated, new generation readers from within Karnataka who have no access to these texts in Kannada. Our doyens of Modern Kannada Renaissance at the turn of the 20th century successfully created a new reader base for texts of antiquity — ancient and medieval — by translating them in various forms into modern Kannada. They showed how the reader needs to negotiate the translated text on a plank of difference and diversity by meeting it halfway — by acquiring the necessary cultural background, information, ways of engaging with the text, and astute use of critical opinion. Translators can and do enable this process by offering footnotes, endnotes, glossaries, and critical introductions.

Not just that. Navodaya scholars and writers have also striven to create enthusiasm for classics by actively engaging with its dissemination — talking, teaching, and writing about them (rasa vimarshe without carping), to demonstrate what it takes to read the text as a translated text. Taking a leaf out of the Navodaya writers, apart from para-textual material, I have produced an audio roopaka on Harishchandra which offers an entry point for readers into the English version. Available on the website of The Murty Classical Library of India, this podcast provides the historical and religious context of the poet, and discusses the high points of the narrative quoting the Kannada original and its English translation. But most importantly, the roopaka presents the Kannada excerpts in Gangamma Keshavamurthy’s inimitable rendering in Gamaka singing, an art form which has kept classics alive in the hearts of our common people for centuries. I have offered over 50 talks on ‘Harishchandra’ at various venues. I have penned down several essays in Kannada and English about the ‘misery and splendour’ of translating the text. All in the hope of bringing alive the text rather than leaving it in cold print.

Indian philosophical thought has used two contrasting tropes to describe the relationship between God and human beings: mārjāla kiṡōra nyāya, which likens it to a mother cat that takes the entire onus for carrying the kittens by the neck; and markaṭa kiṡōra nyāya, which likens it to a mother monkey that helps carry the baby while the little monkey holds on to the mother tight. Reading a translation is more ‘monkey business’ if you like.

Why bother? For the same reason that we play sudoku or chess, scale the Himalayas or go deep sea diving. For kāvya-ṡāstra vinōda. For the fun of it…

Viva le Hanuman!

Deccan Herald is on WhatsApp Channels| Join now for Breaking News & Editor's Picks